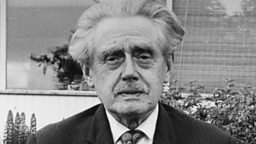

Edwin Muir

1887 - 1959

Biography

Born on the Orkney island of Wyre in 1887, Edwin Muir spent his early years in the idyllic setting of his father's farm, 'The Bu', until increasing farm rents forced the family to move, first to Orkney's mainland and then, in 1901, to Glasgow. This move from the peaceful, agricultural setting of Orkney to industrialised Glasgow was extremely traumatic for Muir, and he would later describe it as a descent from the innocence of a rural Eden into Hell. Conditions in Glasgow were hard and, within a few years of their arrival, two of his brothers and both his parents were dead. The remaining siblings chose to go their separate ways and Muir found himself adrift in a large city with little education or prospects.

From this background, Muir worked in a number of menial jobs and became increasingly interested in left-wing politics, as did many writers of the early-twentieth-century in Scotland. In 1916 he began contributing poetry to a magazine called New Age under the pseudonym 'Edward Moore', and his first book, a volume of short pithy essays on society, politics and the arts, entitled We Moderns, was published in 1918.

1918 was also the year in which he met his future wife, Willa Anderson, who, as , would later become well-known as a novelist. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the Muirs travelled extensively throughout Europe, living in Prague, Dresden, Vienna, Salzburg and Rome. This lifestyle of constant travel can be seen, in part, to reflect a sense of displacement or rootlessness which originated in Muir's early departure from Orkney, and which stayed with him throughout his life.

Muir, in these years, became increasingly interested by developments in modernist European literature and, with Willa, translated more than forty novels from German, including those of Franz Kafka. He was also gaining a reputation as a literary critic and poet, although his first collection, First Poems, was not published until 1925 when he was thirty-eight.

Today, he is identified as one of the central figures of the modern , both for his poetry and for his book Scott and Scotland (1936), in which he argued controversially that Scottish literature would have a better chance of international recognition if it were to be written in English, a line that brought him into conflict with , the major literary force of the period.

In 1946 he was appointed Director of the British Council and the couple returned to live in Prague, and then Rome. In 1950 he became warden of Newbattle Abbey College, an adult education centre in Midlothian where he encouraged the early writing of , a fellow Orcadian. Although he only returned to Orkney for holidays, the islands remained a central reference-point throughout his life, a fact which was detailed in his autobiography, initially entitled The Story and the Fable (1940) but later re-worked as An Autobiography (1954).

In 1955 Muir was made the Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University in the USA, before returning to England, where he died at Cambridge in 1959. He is buried nearby in the village of Swaffham Prior.

Works

Edwin Muir, poet, critic and novelist, was one of the leading contributors to the modern Scottish Renaissance, a movement which was at its height in the interwar years and which sought to revive Scottish writing and promote a national self-confidence. Yet, despite this association with the movement and, through that with writers such as the poet Hugh MacDiarmid, Muir's poetic style and political viewpoint were markedly divergent from the Renaissance norm. Controversially rejecting MacDiarmid's call for the promotion of Scots language poetry and political nationalism, Muir argued, in his 1936 study Scott and Scotland, that Scotland must accept English as the language of its literature. This belief is reflected throughout his collected poetry which, despite his upbringing in Orkney and Glasgow, is written in an English suggestive of a knowledge of contemporary modernists such as Eliot and Pound. Furthermore, his work largely avoids the stylistic innovation associated with poetry of the Renaissance and, for this reason, it is necessary to view his work in a context that is European as much as it is Scottish.

Muir's early poetry, which includes First Poems (1925) and Variations on a Time Theme (1934), is heavily informed by memories of his Orkney childhood, and the pre-lapsarian (or Edenic) idyll which he associated with it. The life-shattering contrast he experienced between this rural vision and the hellish reality of industrial Glasgow is detailed in his autobiography, first published as The Story and the Fable (1940), a text which many readers find useful as an introduction to the recurring personal themes of his other writings.

Indicative of this early period is 'Childhood', a poem from First Poems which, written in the regular four line stanza of the Scottish ballad form, is reassuring in both its regularity and simplicity. In style, it is reminiscent of Blake's Songs of Innocence, while some readers perceive an affinity with Wordsworth in his evocation of childhood. Its structural simplicity reflects, from the archaic suggestion of 'Long time he lay', a security of belonging, distantly remembered from an adult perspective. Encapsulating the safe and timeless quality of the memory are phrases such as 'securely bound', 'tranquil air' and 'still light'. The speaker is encircled and protected, both by his parents, who are present in the first and last lines of the poem, and by nature itself in the life-like rocks which 'sleep round him where he lay'. While the outside world is suggested by the 'new shores' and alliterative description of a passing ship, it does not impose itself on the peaceful vision and barely hints at the external horrors that will later so shatteringly force their way into Muir's consciousness.

The later poetry, from The Narrow Place (1943) to his final collection One Foot in Eden (1956), is considered his most mature and accomplished. This period is also, for the most part, more positive in outlook than his early work, although, paradoxically, the most anthologised poem of this group, 'The Horses', deals with his fears for the Cold War and his growing realisation of the nuclear age. Echoing and subverting the seven-day creation in Genesis, the poem depicts the aftermath of an unspecified world war which has rendered useless the machinery and illusory benefits of the modern age. The dumb radios and obsolete planes and tractors force the survivors to remember an older way of life, long abandoned; their return to the plough seen as the revitalisation of a lost communion between man and the world, 'Far past our fathers' land'. While the poem is not formally arranged in two parts, it is effectively read as such, with the first thirty lines depicting the world laid waste to atomic ruin, and the second section offering new beginnings, symbolised by the return of the horses of the poem's title.

The arrival of the horses is heralded by their alliterative soundings, first a 'tapping', growing to a 'deepening drumming' and then 'hollow thunder', before bursting into the silence with the promise of cyclical regeneration. The anticipation of their appearance is further heightened by the pause, 'We saw the heads/ Like a wild wave charging'. This vision of the horses as 'fabulous steeds set on an ancient shield', emphasises their mythical qualities, symbolic of both Muir's Orkney and of a timeless knowledge. Through re-found co-operation with the mysterious beasts, 'that long-lost archaic companionship', there is hope for recovery and a meaningful future, acknowledged in the final line, 'their coming our beginning'.

Less well known are Muir's three novels, The Marrionette (1927), The Three Brothers (1931) and Poor Tom (1932), the last two of which explore, in different guises, the traumatic experience of early industrial Glasgow. Muir's primary identification with Orkney leads him to characterise Scotland as 'my second country' and two further texts which deal directly with this are Scott and Scotland, referred to above, and Scottish Journey (1935), an unusual volume of travel writing in which he explores Scotland's Calvinist inheritance with often unflattering portraits of the Scottish land and people. Muir's collected poetry is available as Collected Poems (1991), edited by Peter Butter.

Reading Lists

Primary

We Moderns (1918)

Latitudes (1924)

First Poems (1925)

Chorus of the Newly Dead (1926)

Transition (1926)

The Marionette (1927)

The Structure of the Novel (1928)

John Knox: Portrait of a Calvinist (1929)

The Three Brothers (1931)

Poor Tom (1932)

Variations on a Time Theme (1934)

Scottish Journey (1935)

Scott and Scotland (1936)

Journeys and Places (1937)

The Present Age from 1914 (1939)

The Story and the Fable (1940)

The Narrow Place (1943)

The Voyage (1946)

The Labyrinth (1949)

Essays on Literature and Society (1949)

Collected Poems (1952)

An Autobiography (1954)

One Foot in Eden (1956)

The Estate of Poetry (1962)

Collected Poems, 1921-1958 (1960)

Selected Poems,聽ed. by T. S. Eliot聽(1965)

Selected Letters, ed. by P H Butter聽(1974)

Uncollected Scottish Criticism,聽ed. by A Noble (1982)

Selected Prose聽ed. by 0 M Brown (1987)

The Truth of Imagination: Some Uncollected Reviews and Essays,聽ed. by P H Butter聽(1988).

Related Links

Writing Scotland themes

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall