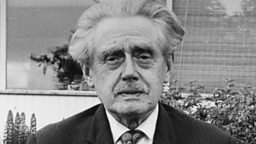

Irvine Welsh

Scottish fiction writer.

Biography

Irvine Welsh was born in Leith. He moved with his family to Muirhouse, in Edinburgh, at the age of four. Welsh left Ainslee Park Secondary School when he was sixteen and went on to complete a City Guild course in electrical engineering. Thereafter, Welsh worked as an apprentice TV repairman until an electric shock persuaded him to abandon this work in favour of a series of other jobs, before leaving Edinburgh for the London punk scene in 1978. There, Welsh played guitar and sang in The Pubic Lice and Stairway 13. Later, he worked for Hackney Council in London and studied computing with the help of a grant from the Manpower Services Commission. After working in the London property boom of the 1980s, Welsh returned to Edinburgh where he worked for the city council in the housing department. He went on to study for an MBA at Heriot Watt University, writing his thesis on creating equal opportunities for women.

Welsh published stories and parts of what would later become Trainspotting from 1991 onwards in DOG, the West Coast Magazine, and New Writing Scotland. Duncan McLean published parts of the novel in two Clocktower pamphlets, A Parcel of Rogues and Past Tense: Four Stories from a Novel. Meanwhile Kevin Williamson, a member of Duncan McLean’s Muirhouse writers’ group, published sections of Trainspotting in the literary magazine Rebel Inc. Duncan McLean recommended Welsh to Robin Robertson, then editorial director of Secker & Warburg, who decided to publish Trainspotting, despite believing that it was unlikely to sell.

When Trainspotting was published in 1993 Irvine Welsh shot to fame. The novel was apparently rejected for the Booker Prize shortlist after offending the ‘feminist sensibilities’ of two of the judges (Purlock, 1996). Despite this unease from the critical establishment, Welsh’s novel received good reviews. Harry Gibson’s stage adaptation of the novel was premiered at the Glasgow Mayfest in April 1994 and went on to be staged at the Edinburgh Festival and in London before touring the UK. In August 1995, Irvine Welsh gave up his day job.

Since Danny Boyle’s film adaptation of Trainspotting was released in February 1996 Irvine Welsh has remained a controversial figure, whose novels, stage and screen plays, novellas and short stories have proved difficult for literary critics to assimilate, a difficulty made only more noticeable by Welsh’s continued commercial success.

Works

Irvine Welsh’s first novel, Trainspotting (1993), is set mostly in Leith and Edinburgh in the 1980s and consists of a series of loosely connected episodes which follow Welsh’s characters as they tell their stories of sex, drugs and dance music. The novel’s energy comes in part from the degree to which Welsh gives such distinctive voices to each of his characters, expecting his readers to tune in and recognise them with the first few words they speak.

Trainspotting gained notoriety for its depiction of Edinburgh heroin culture; the novel is set at a time when Edinburgh was thought to be the ‘HIV capital of Europe’. While heroin is undoubtedly crucial to many of the narratives in Welsh’s first novel, Trainspotting draws its readers’ attention to aspects of Scottish and British culture which are perhaps even more uncomfortable. Trainspotting talks about poverty, sectarianism, racism and attitudes towards disability, above all insisting that if there is no such thing as society, there is certainly no such thing as a classless society.

Welsh’s characters are often highly sceptical about the ability of therapists, activists or politicians to change society for the better. For Mark Renton, the state’s attempt to bring him off heroin is a symptom of society’s inability to deal with someone who has consciously chosen to reject its values; ‘ah choose no tae choose life. If the cunts cannae handle that, it’s thair fuckin problem’ (Trainspotting, 188). Renton insists on his individual right to opt out of society, to take his life in his own hands, and refuses to allow society the option to view his rejection as a curiosity of medical science. This individualism also marks a rejection of socialist representations of the Scottish working class, which insisted upon class solidarity and the potential of collective action.

Welsh followed Trainspotting with a novella and collection of short stories called The Acid House (1994). One aspect of the use of drugs in Welsh’s fiction is that it has allowed him to integrate elements of fantasy into his portrayals of urban life. So, in the title story, ‘The Acid House’, Welsh has Hibs casual Coco Bryce exchange minds with a young baby, and then follows the baby and Coco as their mother and girlfriend try to make them into the men they want them to be. Elsewhere, in ‘The Granton Star Cause’ Boab meets God in the pub and is then turned into a bluebottle.

Whereas Trainspotting is told in a cacophonous surround sound, Marabou Stork Nightmares (1995) is a monologue. Roy Strang is in a coma after a failed suicide attempt. He uses fantasy to avoid remembering the real life that has brought him here, from his childhood in Muirhouse, through his family’s attempt to make a new life for themselves in apartheid South Africa and Roy’s subsequent return to Scotland and time as a football casual. The comparison Roy makes between the poor of Edinburgh and black South Africans under apartheid, along with the novel’s representation of rape, has made Marabou Stork Nightmares the most controversial of Welsh’s books to date.

For Glue (2001), Irvine Welsh returned to the polyphonic style he employed in Trainspotting. Glue is Welsh’s longest book to date and also his most ambitious in scope. For the first time in an Irvine Welsh novel he takes us through three decades of his characters’ lives, from the 1970s to the early years of the new millennium. This allows Welsh to explore his four principal characters, Terry Lawson, Carl Ewart, Billy Birrell and Andrew Galloway, as they develop and change over time, charting their reactions to the changing world around them.

The novel begins with its four characters’ parents in a Scotland so markedly different from the Scotland of Welsh’s earlier novels. It then moves to their children as they grow up in 1970s Edinburgh, beginning with Terry Lawson’s first day at school. The novel varies between a third person narrative and the distinctive individual voices of its characters. The early section of Glue takes the traditional ‘young man growing up’ narrative and transforms it, replacing the individual focus of that form with an examination of how different people develop differently under similar circumstances. Welsh also takes away the soft-focus lens, refusing to censor his characters or sanitise their experiences. As Glue progresses, and its characters move from childhood to youth to middle age, it explores, in a more sustained way than elsewhere in Welsh’s work, the solidarity rejected at the end of Trainspotting. Glue is about friendship as much as it is about anger and inequality.

Porno, the sequel to Trainspotting, was published in 2002. The events of the novel can be dated quite precisely, occurring after the opening of the new Scottish Parliament, but before Alex McLeish left Welsh’s beloved Hibernian football club to manage Rangers. In Porno, Welsh brings the Trainspotting characters back together, still suffering from the collective hangover caused by Mark Renton’s getaway to Amsterdam at the end of the earlier novel. It is a common feature of Welsh’s fiction that characters from one book have cameo roles in another, creating a sense that each of Welsh’s stories takes place within a wider world in which there is always something going on offstage.

Related Links

Writing Scotland themes

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall