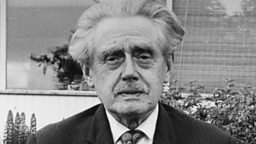

Neil M Gunn

1891 - 1973

Biography

Neil (Miller) Gunn was born in Dunbeath, a small fishing and crofting community in Caithness, North East Scotland, in 1891. Although he was educated in Galloway, he grew up with a love of the Highlands and Highland culture and, as an adult, he returned to the North East to live and work.

Gunn, the son of a fisherman, was born at a time when the herring fishing industries of Scotland were beginning to die out, and much of Highland culture was in decline, with a falling population and growing unemployment. He saw that Highland culture was also under threat as the old ways were forgotten, and fewer people spoke Gaelic or Scots, so traditional songs and stories were beginning to disappear. Reflecting this trend, Gunn himself spoke only English, although in his writing he used the rhythms and syntax of Gaelic speech to give a sense of the people and communities he depicted.

For a number of years, Gunn worked in London for the Civil Service before joining the Customs and Excise in 1911. Returning to the Highlands, Gunn worked as an Excise Officer until 1937, when increasing financial success allowed him to become a full-time writer. This writing also extended to journalism and, in the 1930s and early 40s, he wrote articles for publications such as the Scots Magazine. In this he argued that the Highland way of life was worth preserving and should be supported to stop it disappearing altogether, a position which he also expressed politically through his involvement with the SNP.

Gunn is best known, however, for his novels, the first of which, The Grey Coast was published in 1926. His early novels reveal a bleak, often harsh, portrait of the communities he knew so well, although through time his fiction shifted to reveal a more hopeful vision of Highland experience. These more positive portraits include Highland River (1937), The Silver Darlings (1941) and Young Art and Old Hector (1942), novels which remain his most widely-read work.

In 1956 he published his final book, The Atom of Delight, a spiritual autobiography which traced his interest in Zen Buddhism. Gunn died in 1973. He is recognised as one of the major writers of the renaissance of Scottish literature in the early twentieth century and the Dunbeath Heritage Centre in Caithness houses a permanent exhibition of his life and work.

Works

Neil Gunn is a novelist whose work, more than any other writer, captures the essence of Highland life. He is one of the central figures of the , and is often acknowledged as the most important Scottish novelist of the early twentieth century.

Between 1926 and 1954 Gunn wrote twenty novels, and these can be divided into three major groups. His early novels, among them The Grey Coast (1926), Morning Tide (1930) and Butcher's Broom (1934), focus on the decline of Highland culture, offering often bleak portraits of the north-east fishing and crofting communities that Gunn knew so well.

These were followed by a period of more positive representations which have been described as his 'novels of essential Highland experience' and include Highland River (1937), The Silver Darlings (1941) and Young Art and Old Hector (1942). This group is Gunn's most assured work and these are the novels for which he is best known.

Finally, his later novels, such as Second Sight (1940), The Silver Bough (1948) and The Lost Chart (1949), often more philosophical in character and set in urban surroundings, question the condition of modern life, and the accompanying threat he perceived as moral decay and the loss of personal freedom.

In The Silver Darlings, probably Gunn's most widely-read novel, the Highland people have been uprooted from their traditional lifestyle of crofting by the clearances and have re-established themselves by the sea, which they harvest as once they did the land. They slowly develop a bond with the sea, which is at first tentative and unskilled, but which grows in confidence through the exploits and risk-taking of men like Roddie and, later, Finn. As the generations mature, the connection to the land is weakened and instead of the sea being viewed by a land-bound people, the novel's perspective moves off-shore. The financial incentive which originally destroys the Caithness community (in which sheep take precedence over people), is once more encouraged by the wealth which begins to pour in from the fishing creels spilling with herring, the silver darlings of the title.

Gunn believed that the repetition of song and folk tales was vital to keep Highland culture from extinction. In The Silver Darlings, the art of oral narrative remains alive in the house of Meg the net maker, and in the old men of the isolated island communities that the fishing boats occasionally visit. Finn earns respect through performance of his developing craft when, with timing and vision he recounts his sea adventures to a captive audience. Admiration for this is expressed through his likening to the legendary story-teller, Finn MacCoul. Also of importance in the preservation of an older culture is the remembrance of protracted family histories, a central task amongst largely illiterate communities. In doing this, Kirsty and Rob are portrayed as keepers of 'a maze of kinship very involved and bridged at bloodless gaps by marriage'.

Like many writers of early twentieth-century Scotland, Gunn believed in a lost 'Golden Age', a time in the distant past when man was in touch with nature and his surroundings, in contrast to the complexity and disintegration of modern life. Reflecting this, in Highland River, Kenn, the novel's protagonist, returns as an adult from the destruction and chaos of the First World War to the Highland village of his childhood, in search of the wholeness and harmony he has lost. The novel has an unusual structure as it slips between the events of the present, and the past of Kenn's early years, although the plot is ultimately grounded in Kenn's childhood thoughts which are presented to the reader in a 'stream-of-consciousness' style typical of the modern period.

The adult Kenn鈥檚 desire is to get to the source of the Dunbeath River, in which he fished for salmon as a child and where, he believes, he will rediscover peace and delight. In doing so he will also be following the course of the salmon who, each year make the arduous journey upstream to spawn and die.

Kenn's quest to 'get back to the source of ... life ... the source of the river and the source of himself' is also clearly influenced by the psychoanalytic work of Jung who promoted an interest in mythology and was popular amongst many of Gunn's contemporaries. Jung's writing on 'archetypes', symbols endlessly repeated throughout human history, and on the notion of a shared or 'collective' unconscious is apparent throughout Highland River and many of Gunn's other works.

The importance of tradition in Gunn's work also had, at its heart, the more contemporary and political aims of a 'Scottish Renaissance'. This desire is apparent throughout his fiction and was shared by other writers of the time, such as Edwin Muir and Hugh MacDiarmid. They believed that, in order to succeed, a renaissance must come from economic development and political independence as well as from a vibrant and living culture. Reflecting this, Gunn's more overtly political writings can be found in a collection of essays entitled The Man Who Came Back (1991), edited by Margery Palmer McCulloch, as well as in his Selected Letters (1987), edited by JB Pick. Finally, you may be interested to read his allegorical history, Whisky and Scotland: A Practical and Spiritual Survey (1935).

Reading Lists

Primary

Grey Coast (1926)

Morning Tide (1931)

The Last Glen (1932)

Sun Circle (1933)

Highland River (1937)

Second Sight (1940)

The Silver Darlings (1941)

Young Art and Old Hector (1942)

The Green Isle of the Great Deep (1944)

The Serpent (1948)

The Well at the World's End (1951)

Blood Hunt (1952)

The Key of the Chest (1966)

Butcher's Broom (1977)

Whisky and Scotland (1977)

Drinking Well (1978)

Lost Glen (1985)

Silver Bough (1985)

Lost Chart (1987)

The Man Who Came Back (1987)

Off in a Boat (1988)

Other Landscape (1988)

The Atom of Delight [Autobiography] (1989)

Highland Pack (1989)

Secondary

Neil M. Gunn: The Man and the Writer edited by Alexander Scott and Douglas Gifford (1973)

Neil M. Gunn: A Highland Life by F. R. Hart and J. B. Pick (1981)

Essays on Neil M. Gunn edited by David Morrison (1971)

Neil M. Gunn and Lewis Grassic Gibbon by Douglas Gifford (1983)

The Novels of Neil M. Gunn: A Critical Study by Margery McCulloch (1987)

A Bibliography of the Works of Neil M. Gunn by C. J. L. Stokoe (1987)

A Celebration of the Light: Zen in the Novels of Neil Gunn by John Burns (1988)

Neil Gunn's Country: Essays in Celebration of Neil Gunn edited by Diarmid Gunn and Isobel Murray (1991)

The Fabulous Matter of Fact: The Poetics of Neil M. Gunn by Richard Price (1991)

Related Link

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall