What鈥檚 the best way to beat Stress?

Stress is extremely common in the UK. Chronic stress can increase the likelihood of developing more serious mental health conditions and is also linked to a host of problems with your physical health such as heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

There are many methods that claim to help reduce stress but only some are supported by scientific evidence.

Trust Me, I’m a Doctor wanted to put some of these to the test to find out which might be most effective.

How to measure changes in stress

No matter the source of the stress, the physiological response of the body is broadly the same. We produce a variety of stress hormones, chemical messengers that instruct the body to react. Adrenaline, noradrenaline and cortisol are examples of stress hormones.

Cortisol is one of the main players in this stress response. Levels of this hormone increase in times of stress, but it’s also produced as a healthy and normal part of the body’s 24 hour cycle.

Cortisol is at its lowest overnight and starts to rise prior to awakening with a peak as we wake up in the morning. It’s this peak of cortisol that wakes us up and provides us with the energy to cope with the day ahead. This is called the cortisol awakening response (CAR).

In someone who is not particularly stressed, CAR rises sharply in the morning and quickly tails off, dropping consistently during the day, falling to low levels towards bedtime and dipping still lower during the night.

If we suffer from chronic stress it can interfere with this healthy pattern. In someone who is chronically stressed, the peak of CAR is lower (we don’t produce as much in the morning to help us get going), levels of cortisol can remain higher during the day and do not fall to a healthy low level during the night.

In the long term this hormone imbalance can have a negative impact on your health.

The experiment

We teamed up with Prof Angela Clow and Dr Nina Smyth from the University of Westminster to compare the effect on CAR of three activities that are commonly thought to reduce stress.

We recruited 71 participants who described themselves as stressed, and split them into 4 groups to follow one of the selected activities for 8 weeks.

Group 1 joined weekly group gardening and conservation sessions. Research indicates that social interaction, physical activity and contact with nature can have positive effects on mental wellbeing.

Group 2 followed twice-weekly yoga classes. Traditionally believed to reduce stress, studies suggest that yoga can lower blood pressure and heart rate.

Group 3 did regular sessions of mindfulness. This is a form of meditation that aims to focus the mind on present sensations. This group used a leading mindfulness phone app for ten minutes a day.

We also included a control group who carried on their lives as usual. At the end of the study, all groups were given the opportunity to continue, or begin to take part in, the activities we tested.

We collected saliva samples throughout the day (to measure cortisol) on two days: at the start of the study and again at the end of the study. We also asked our volunteers to complete questionnaires designed to assess levels of stress, anxiety and depression during the study period. We recorded their activity levels and waking times using wrist-worn activity monitors.

We wanted to see if any of the intervention activities reduced our volunteers’ stress, as measured by their CAR and cortisol patterns over the test days, and responses to the questionnaires completed throughout the study period.

The Results

All three interventions reduced stress by the measures we used.

Looking at the cortisol data for the groups, mindfulness had the biggest positive impact on stress as defined by the greatest increase in CAR. Group gardening and conservation activities also improved CAR, though less so than mindfulness. Yoga did not make a statistically significant improvement to CAR, but did cause a healthy reduction in cortisol levels later in the day.

The questionnaire data also supported the benefits of these activities, with reported stress reducing on average in all three groups.

However, the most surprising finding from the cortisol data, was that these activities only helped to reduce stress if the participants enjoyed doing them.

When our volunteers enjoyed their activity, their CAR in the morning improved significantly. When they did not enjoy the activity, there was no significant increase in CAR.

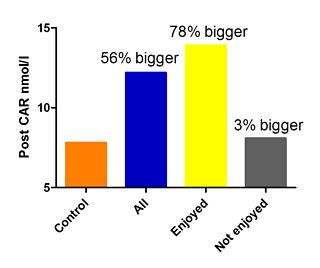

Figure 1: CAR for mindfulness group, post intervention vs control group

Mindfulness had the most significant impact on the CAR with an improvement of 78% in the people who enjoyed it.

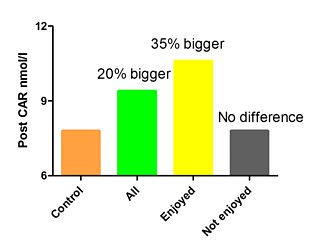

Figure 2: CAR for outdoor activity group post intervention vs control group

Next was the group gardening and conservation activity, where those who enjoyed it experienced a 35% increase in CAR.

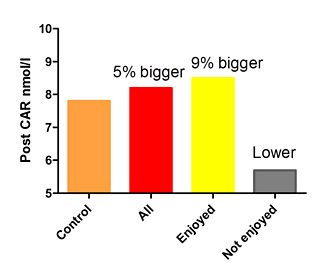

Figure 3: CAR for the yoga group, post intervention vs control group

Lastly, the yoga group: they did not experience a statistically significant increase in CAR (but did have the best impact on reducing cortisol levels during the day).

Conclusions

Taking part in any one of these activities can potentially help make a healthy improvement to your stress levels. Outdoor group activity, yoga and mindfulness all had a stress-reducing effect by at least one of the measures we used, with mindfulness appearing to be the most effective overall in our study.

However, whether you try one of these, or a completely different stress-reducing activity, our experiment suggests it is essential to choose something you enjoy in order for it to be effective.