Pillar of Ashoka

A global history of the world told through objects at the British Museum. This week Neil MacGregor is exploring power around the world over 2000 years ago. Today he is in India.

The history of the world as told through objects at the British Museum arrives in India over 2000 years ago. Throughout this week Neil MacGregor is exploring the lives and methods of powerful new leaders.

Today he looks at how the Indian ruler Ashoka turned his back on violence and plunder to promote the ethical codes inspired by Buddhism. He communicated to his vast new nation through a series of edicts written on rocks and pillars. Neil tells the life story of Ashoka through a remaining fragment of one of his great pillar edicts and considers his legacy in the Indian sub-continent today. Amartya Sen and the Bhutanese envoy to Britain, Michael Rutland, describe what happened when Buddhism and the power of the state come together.

Producer: Anthony Denselow

Last on

![]()

More programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects related to leaders & government

About this object

Location: Uttar Pradesh, India

Culture: Ancient South Asia

Period: About 238 BC

Material: Stone

��

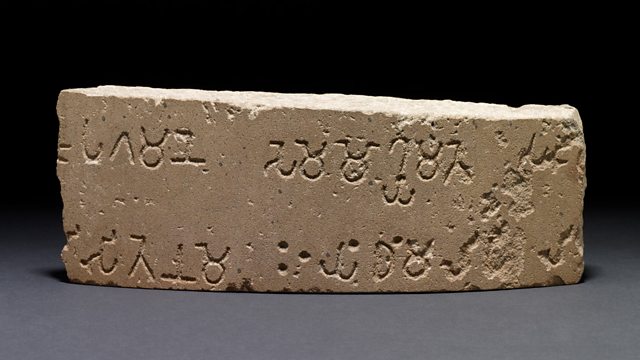

This fragment comes from one of the pillars erected throughout India by the Emperor Ashoka around 240 BC. The type of writing used for the inscription is known as 'Brahmi' and forms the basis for all later Indian, Tibetan and South-East Asian writing. This inscription outlines Ashoka's personal philosophy ? a system similar to Buddhism ? on how people should live their lives. In this pillar, Ashoka speaks of how the greatest conquest is over one's personal morals ? not over other people or lands.

Who was Ashoka?

Ashoka was the most famous king of the Mauryan Empire ? one of the largest empires in the history of South Asia. At their height, the Mauryans controlled most of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. As a young man Ashoka was renowned for his hedonism and cruelty. However, later in life he felt intense remorse triggered by a massacre that occurred during one of his conquests. This inspired him to renounce violence and follow dharma ? a self-defined path of righteousness that guided him through life.

Did you know?

- A carving of four lions that once topped one of Ashoka's pillars at Sarnath is now the national emblem of India.

A man of peace

By Michael Rutland, British Consul in Bhutan

��

It is always said that Ashoka, after winning a great battle, turned into a man of peace. Bhutan does not have great battles but some few years ago the fourth king personally led the very small Bhutanese army down to the south east to expel some thousands of Indian separatist rebels who were fleeing into Bhutan after attacking the Indian army in Assam.

Before he sent he made a speech to the army in which he said we must try not to kill people. It was a successful operation, in just three days all these rebels were flushed out and when the king returned to the capital there was some suggestion that there should be a triumphal entry and all the flags were put up and the invitation cards sent out. But no, that was not his style. His view was this; some people had been killed, there is nothing to celebrate. And so he returned quietly with no celebrations, no triumphalism – something I feel that Ashoka would have felt very at home with.

A griefless emperor

By Amartya Sen, University Professor and Professor of Economics and Philosophy at Harvard University.

��

Ashoka… Shok is grief in Sanskrit. Ashoka is griefless, so there is a kind of commitment to happiness. We don’t know if he was born with that name or not; he may have been called just that – my name, Amartya, means immortal – I know that’s not true. In his case, it might have been more true!

But certainly he is associated with good governance. He is associated with the unity of India as one of the first emperors ruling all over the land – the entire land – he is associated with Indian secularism because of his religious neutrality. He became quite famously converted from Hinduism to the new religion of Buddhism, but his argument was that all the religions would have equal status and recognition and get attention from the others. So secularism in the Indian form, not no religion in government matters, but not favouritism of any religion over any other. That interpretation of secularism, which Akbar pursues, actually originates in fact with Ashoka.

Then there is the issue of democracy, and democracy as governed by discussion, that’s very big in Ashoka, namely that you have to discuss and you have to arrive at a conclusion and that’s the best way to govern.

Broadcasts

- Tue 18 May 2010 09:45���˿��� Radio 4 FM

- Tue 18 May 2010 19:45���˿��� Radio 4

- Wed 19 May 2010 00:30���˿��� Radio 4

- Tue 1 Dec 2020 13:45���˿��� Radio 4

Featured in...

![]()

Leaders and Government—A History of the World in 100 Objects

More programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects related to leaders & government

Podcast

-

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, retells humanity's history through objects