Head of Alexander

Another chance to hear Neil MacGregor's global history told through objects from the British Museum. This week he is with the great rulers of the world over 2000 years ago.

Another chance to hear the first programmes in the second part of Neil MacGregor's global history told through objects from the British Museum. This week Neil is exploring the lives and methods of powerful rulers around the world 2000 years ago, asking what enduring qualities are needed for the perfect projection of power.

Contributors include the economist Amartya Sen, the politician Boris Johnson, political commentator Andrew Marr and the writer Ahdaf Soueif.

Neil begins by telling the story of Alexander the Great through a small silver coin, one that was made years after his death but that portrays an idealised image of the great leader as a vigorous young man. Neil then considers how the great Indian ruler Ashoka turned his back on violence and plunder to promote the ethical codes inspired by Buddhism. Neil tells the life story of Ashoka through a remaining fragment of one of his great pillar edicts and considers his legacy in the Indian sub-continent today. The third object in today's omnibus is one of the best known in the British Museum, the Rosetta Stone. Neil takes us to the Egypt of Ptolemy V and describes the astonishing contest that led to the most famous bits of deciphering in history - the cracking of the hieroglyphics on the Rosetta Stone. An exquisite lacquer wine cup takes Neil to Han Dynasty China in the fourth programme and the omnibus concludes with the 2000 year old head of one of the world's most notorious rulers - Caesar Augustus.

Producers: Anthony Denselow and Paul Kobrak.

Last on

More episodes

Previous

You are at the first episode

![]()

More programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects related to leaders & government

About this object

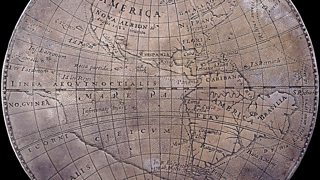

Location: Lampsakos (modern Turkey)

Culture: Ancient Middle East

Period: 305-281 BC

Material: Silver

��

This coin was issued by Lysimachus, the former general of Alexander the Great. After Alexander's death, Lysimachus ruled part of Alexander's empire in Bulgaria, northern Greece and Turkey known as 'Thrace'. Lysimachus used Alexander's portrait on his coins to emphasise his position as Alexander's successor. Alexander was worshipped as a god after his death. Here he sports the ram's horns of the god, Zeus Ammon, whom Egyptian priests claimed was Alexander's father. On the reverse of the coin is the goddess Athena.

Who was Alexander the Great?

Alexander was born in the kingdom of Macedon in 356 BC. By the age of 25 he had conquered Greece, Egypt and Persia, creating an empire spanning 2 million square miles. Following his death in 323 BC, Alexander's generals began to squabble over his legacy. Since they could not claim a blood-tie, these generals tried to legitimise their rule through other connections with Alexander. Eventually they divided the empire into three main kingdoms in Macedon, Egypt and Persia and went on to form powerful dynasties.

Did you know?

- Lysimachus was a great hunter and it was said that Alexander shut him in a cage with a lion to test his prowess.

Heads or tails?

By Andrew Meadows, Deputy Director, American Numismatic Society

��

With this startling image of Alexander the Great we are at the beginning of a tradition of portraiture on coins that extends to the modern day. But why does such portraiture begin only around 300 BC, three centuries after the invention of coinage, and why with Alexander the Great?

The clues lie in the portrait itself. Alexander is not portrayed as a man, but as a god. He bears the attribute of Zeus Ammon, an allusion to the claim that he was this god's son. As such, the 'portrait’, in fact fits into a tradition that had existed since the birth of coinage.

The head of a deity was an entirely appropriate subject for depiction on a coin, and thousands of examples exist in the corpus of Greek coinage. So Alexander the 'god', not Alexander the 'man' is the design of Lysimachus' coin. And this fact explains too why it was only now that the head of someone we would regard as a man could appear on a coin. For it is with Alexander the Great that the Greek process of deifying once mortal men begins in earnest. In the case of Alexander this portrayal began only after his death, but within a generation of this living kings would be portrayed on coins, albeit initially with attributes that suggested their deification.

At one level, it strikes the modern eye as odd that the Greeks should have been so reluctant to portray a man on their coins. We are used today, especially those of us who live in monarchies, to seeing the current head of state depicted on our coinage.

Yet the impact of such images, although perhaps muted to those who see such portraits on a daily basis, is still powerful in some cultures. One has only to think of the coinage of one of the world’s largest democracies, to see the taboo in action in the modern world. No living individual is yet portrayed on the circulating coinage of the United States, which uses instead a gallery of dead presidents where other nations acknowledge the living.

Transcript

Broadcasts

- Mon 17 May 2010 09:45���˿��� Radio 4 FM

- Mon 17 May 2010 19:45���˿��� Radio 4

- Tue 18 May 2010 00:30���˿��� Radio 4

- Mon 30 Nov 2020 13:45���˿��� Radio 4

Featured in...

![]()

Leaders and Government—A History of the World in 100 Objects

More programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects related to leaders & government

Podcast

-

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, retells humanity's history through objects