Episode Transcript – Episode 90 - Jade bi

Jade bi (inscribed in the eighteenth century), from China

The first four programmes of this week were about the European Enlightenment's project of mapping and understanding new lands. Today's object is from China, at a time when it was pursuing its own Enlightenment, under the Qianlong Emperor who, like his European contemporaries, devoted considerable attention to exploring the world beyond his own borders. In 1756, for instance, he sent out a multicultural task-force - two Jesuit priests, a Chinese astronomer and two Tibetan lamas - to map the territories that he had annexed in Asia. The knowledge they gained spread across the world, and with it the Qianlong Emperor's reputation.

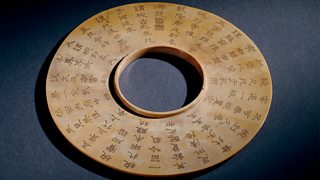

The object in this programme is another product of the Emperor's intellectual curiosity, this time about the Chinese past. It's a jade ring, called a 'bi'. This jade bi, already over three thousand years old when the Emperor decided to study it, is a fine, plain disc with a hole in the centre, of a type often found in ancient Chinese tombs. The Emperor took the unadorned bi, and then had his own words inscribed on it. In doing so, he transformed the ancient bi into a narrative of the eighteenth-century Chinese Enlightenment.

"It's an exploratory document, it reminds us that documents can be made of jade or bronze, just as much as on paper, of course." (Jonathan Spence)

"The piece represented is a deep link between the ancient past and now. It is very cultural, but also political." (Yang Lian)

For Enlightenment Europe, China was a model state, wisely governed by learned emperors. The philosopher and writer Voltaire wrote in 1764:

"One need not be obsessed with the merits of the Chinese to recognise that their empire is the best that the world has ever seen."

Rulers everywhere wanted a piece of China at their court. In Berlin, Frederick the Great designed and built a Chinese pavilion in his palace at Sanssouci. In the grounds of Kew, you can still see the ten-storey Chinese pagoda erected by George III.

In the nearly 60 years of the Qianlong Emperor's reign, from 1736 to 1795, China's population doubled, its economy boomed and the Empire grew to its greatest size for five centuries, more or less to its modern extent - it covered over four and a half million square miles (11,600,000 sq km). The Emperor was a member of the Qing Dynasty, which had displaced the Ming about a hundred years before, and which would rule China until the beginning of the twentieth century. The Qianlong Emperor, owner of the jade bi that is the object of this programme, was a shrewd intellectual and a tough leader, happy to proclaim the superiority of his territorial conquests over those of his predecessors, and to assert for his own Qing Dynasty the backing of the heavenly powers. In other words, he claimed the Mandate of Heaven:

"The military strength of the majestic Great Qing is at its height. How can the Han, Tang, Song or Ming dynasties, which exhausted the wealth of China without getting an additional inch of ground for it, compare to us? No fortification has failed to submit, no people have failed to surrender. In this, truly we look up gratefully to the blessings of the blue sky above to proclaim our great achievement."

This emperor was a successful military leader, an adroit propagandist and a man of culture - a renowned calligrapher and poet, a passionate collector of paintings, ceramics and antiquities. The astonishing Chinese collections in the Palace museums today hold many of his precious objects.

Our bi is one that thoroughly engaged the Qianlong Emperor's attention, and it is not hard to understand why. It is a thin disc of jade, pale beige in colour and just a little bigger than a CD, but with a hole in the middle, with a raised edge around it. We know from similar objects found in tombs that this bi was probably made around 1200 BC. We don't know what it was for, but we can see clearly enough that it is very beautifully crafted.

When the Qianlong Emperor examined this bi, he thought it was both beautiful and intriguing. He was moved to write a poem recording his thoughts on studying it, and he had the poem inscribed on the bi itself:

"It is said there were no bowls in antiquity, but if so, where did this stand come from? It is said that this stand dates to later times, but the jade is antique."

Modern scholars know that jade bi discs are usually found in tombs. The Qianlong Emperor thinks that the bi looks like a bowl stand, a type of object used since antiquity in China. He then shows off his knowledge of history by discussing arcane facts about ancient bowls, and finally decides that he cannot leave this bi without a bowl.

"This stand is made of ancient jade, but the jade bowl that once went with it is long gone. As one cannot show a stand without a bowl, we have selected a ceramic from the Ding kiln for it."

By combining the bi with a much later object, the Emperor has ensured that in his eyes at least, the bi now fulfils its aesthetic destiny. It's a very typical Qianlong way of addressing the past. You admire the object's beauty, you research the historical context, and you present your conclusions to the world as a poem. In the process, he created two new works of art - the poem, which was included in his literary works, and the bi.

The Emperor's poem is incised in beautiful calligraphy on the wide ring of the disc, and it fuses object and interpretation, in what he thought was an aesthetically pleasing form. Chinese characters are spaced so that they radiate out from the central hole like the spokes of a wheel, and these are the very words that I have been quoting. Many of us might see this as defacing an ancient object as a kind of desecration, but that's not how the Qianlong Emperor saw it. He thought that the writing enhanced the beauty of the bi. But he also had a more worldly, political purpose in inscribing his poem on this jade bi. Here's a historian of China, Jonathan Spence:

"There was very much a sense that China's past had a kind of coherence to it, so this new Qing Dynasty wanted to be enrolled, as it were, in the records of the past, as having inherited the glories of the past, and being able to build on them, and to make China even more glorious. And Qianlong was, there's no doubt about it, a great collector. This was Imperial centralised collecting, with a national focus, but also exploring other realms of world art at the same time. And there is a bit of nationalism about his collecting, I think, they wanted to show that Beijing was the centre of this Asian cultural world.

"And the Chinese - according to Voltaire, and other thinkers in the French Enlightenment - the Chinese did indeed have things to tell us Europeans, as it were, in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, important things about life, morality, behaviour, learning, genteel culture, the delicate arts, the domestic arts . . . "

. . . and politics. The Qing Dynasty had one major political handicap. They were not Chinese - they came from modern Manchuria, on the north-eastern border. They remained a tiny ethnic minority, outnumbered by the native Han Chinese by about 250 to 1, and they were famous for a number of un-Chinese things - among them, an appetite for large quantities of milk and cream. So was Chinese culture safe with this Qing Dynasty? In this context, the Qianlong Emperor's appropriation of ancient Chinese history was a deft act of political integration. His greatest cultural achievement was the 'Complete Library of the Four Treasuries', the largest anthology of writing in human history, encompassing the whole canon of Chinese writing, from its origins to the eighteenth century. Digitised today, it fills 167 CD-ROMs. The Chinese poet Yang Lian recognises the propaganda element in the Qianlong Emperor's lyrical description on the bi, and he takes a rather dim view of his poetry as well:

"When I look at this bi I have some very complex feelings. On one side I still very much appreciate [it]. I love this feeling, which is a link with the ancient Chinese cultural tradition, because it was a very unique phenomenon which started from a long time ago and never broke - continually developed until today, whatever [the] difficult times . . . the jade always represents the great past.

"Another side, the darker side . . . the beautiful things have always been used by the rulers, who often had bad taste, so they don't mind to destroy the ancient things with their bad writing, so they can carve the Emperor's poem on the beautiful piece. And also through the writings they tried to do a little propaganda, which for me is very familiar!"

The Qianlong Emperor was no master of poetry - he seems to have mixed classical Chinese with vernacular forms, to what is generally thought to be poor effect. But that didn't hold him back. He published over 40,000 compositions in his lifetime, part of his elaborate campaign to secure his place in history.

And he was largely successful. Although the Qianlong Emperor's reputation dipped dramatically in the Communist period, it is once again strong in China. And recently a very satisfying discovery has been made. You may remember that the Emperor wrote that : "As you can't show a stand like this without a bowl. He had selected a bowl from the Ding kiln for it." Very recently a scholar identified in the collections of the Palace Museum, Beijing, a bowl that carries the same inscription as the one on this disc. It is undoubtedly the very bowl chosen by the Quinlong Emperor to sit in this bi.

As he handled and thought about the bi, the Qianlong Emperor was doing something central to any history based on objects. Thinking about a distant world through things, is not only about knowledge but about imagination, and it necessarily involves an element of poetic reconstruction. With the bi, for example, the Emperor knows that it is an ancient and cherished object, and he asks the question that we are all still asking - what was it for? He decides it's a stand, and he finds a bowl that seems to be a perfect match - but he acknowledges there is a doubt about whether these pieces really belong together. It's unlikely that his answer was correct, that the bi was in fact a bowl stand, but I find myself admiring and applauding his method.

Next week, we're focussed not on the past but on modernity. We're looking at the defining characteristics of the nineteenth-century global order - mass production, mass consumption and mass markets - a world dominated by the economic interests of Europe and North America. It's the world that coined the phrase "time is money", and so we're going to begin with the challenge of accurately telling the time . . . through a ship's chronometer.

-

![]()

Listen to the programme and find out more.