‘A life wasted’: Who was the real Ebenezer Scrooge?

13 December 2022

Mark Gatiss brings A Christmas Carol: A Ghost Story from stage to television screen this Christmas, and Simon Callow's acclaimed one-man adaptation is on ≥…»ÀøÏ ÷ Four and iPlayer on 18 December. The classic holiday season morality tale played a huge role in popularising many of the Victorian ideas of Christmas. But where did Charles Dickens get the idea for curmudgeonly old miser Ebenezer Scrooge?

Charles Dickens was not only one of the greatest novelists of the 19th Century, but also an inspired actor and director, who performed A Christmas Carol around the country as a one-man show. Known for his innate ability to summon each of the 38 characters, Dickens was lauded for his ability to create a riveting world for his audience to inhabit.

Dickens couldn’t have been more wrong about the real Scroggie

But how did the author create Ebenezer Scrooge – "a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner," as Dickens describes him?

It’s been suggested that during a walk in Edinburgh’s Canongate kirkyard in June 1841, Dickens came across the gravestone of one Ebenezer Lennox Scroggie. The gravestone gave ‘meal man’ as Scroggie’s profession, referring to his trade as a merchant.

Somehow Dickens misread this as ‘mean man’ and later wrote in his notebook: "To be remembered through eternity only for being mean seemed the greatest testament to a life wasted."

He couldn’t have been more wrong about the real Scroggie.

Research by political economist Peter Clark has shown that he had been a corn trader and vintner whose family had supplied Captain Cook’s ship Endeavour as it charted the Pacific.

Scroggie imported wine in bulk and exported whisky in return, building a reputation and gaining royal patronage, leading to two years acting as Edinburgh’s Lord Provost. He was a jovial man and a scallywag who once interrupted the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland by goosing the Countess of Mansfield.

He may have taken advantage of one of his servants too, having a child out of wedlock - not the behaviour you would expect from Dickens’ Scrooge; well, maybe after the visitations.

Unfortunately, the grave marker was lost during restoration of the Kirk in 1932. But there are plans to recognise Scroggie and his life by erecting a memorial and drawing attention to his literary influence.

Where do our Christmas traditions come from?

Griff Rhys Jones and historian Daru Rooke discuss the history of Christmas decorations.

Rowan Atkinson's take on the character of Scrooge can be seen in Blackadder's Christmas Carol on Thursday 22 December 2022 at 6:15pm, ≥…»ÀøÏ ÷ Two, or watch now on iPlayer.

Piggy Carol Singers

Ebenezer Blackadder has a surprise in store for some unwitting carol singers.

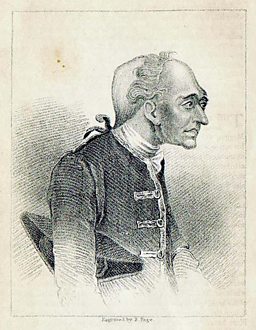

The other inspiration for Scrooge is likely to have been John Elwes (1714-1789), the MP for Berkshire who was born in to a prestigious and wealthy family of reputed skinflints.

Unusually for a miser, Elwes could be affable, considerate and generous with his cash.

Dickens would have known of Elwes through a biography written by Edward Topham, Life of the Late John Elwes (1790), which became a bestseller, going through 12 editions and establishing ‘Elwes the miser’ as the archetypal penny-pincher:

“All earthly comforts he voluntarily denied himself: he would walk home in the rain, in London, sooner than pay a shilling for a coach: he would sit in wet clothes sooner than have a fire to dry them: he would eat his provisions in the last stage of putrefaction sooner than have afresh joint from the butcher's…”

And this was a man who was bequeathed an estate by his uncle which exceeded £18million in today’s money.

Unusually for a miser, Elwes could be affable, considerate and generous with his cash, often lending to those in need (without the usury terms that Scrooge would recognise) - and losing it. “His avarice,” says Topham, “consisted not in hard-heartedness, but in self-denial.” He left the equivalent of over £28million to his children after his death in 1789.

Dickens is certainly no stranger to the miser as a type. It could be said he expanded on the character of Gabriel Grub from The Pickwick Papers (1837).

But while the name Scrooge is now a byword for a selfish, miserly person, the book ends on a note of optimism: “God bless us, every one!” Surely Scroggie and Elwes would applaud that sentiment too.

- A version of this article was originally published in 2015.

Arts Unwrapped

-

![]()

Mark Gatiss on the Christmas ghost story

With Count Magnus coming to TV, The League of Gentleman and Sherlock star reveals why he loves a festive fright

-

![]()

Is this the real Ebenezer Scrooge?

The possible inspiration behind Dickens' Ebenezer Scrooge, literature's most famous misanthropic businessman

-

![]()

Kermode on Christmas: Dark secrets and bad Santas

Mark Kermode's recipe for the perfect Christmas movie... there's one for every taste

-

![]()

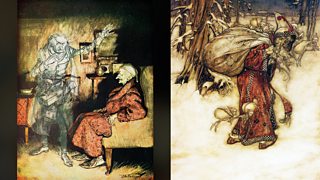

The magical worlds of Arthur Rackham

Christmas gift books and the Golden Age of Illustration with A Christmas Carol, Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens and The Night Before Christmas.

Christmas movie magic from ≥…»ÀøÏ ÷ Arts

-

![]()

Merry Christmas

How cinema has brought Christmas cheer to our screens for over a century, from It's a Wonderful Life to Elf.

-

![]()

Kermode on Christmas

From ≥…»ÀøÏ ÷ Alone and It's a Wonderful Life to action films like Die Hard and slasher favourite Black Christmas, there's something for every taste

-

![]()

Unmerry Christmas

From The Grinch to Bad Santa, this festive trip to the cinema is guaranteed to bring an icy tear to your cheek.

-

![]()

Five life lessons from classic Christmas movies

Unwrapping the hidden wisdom in Christmas movies.

More from ≥…»ÀøÏ ÷ Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms