Episode Transcript – Episode 72 - Ming Banknote

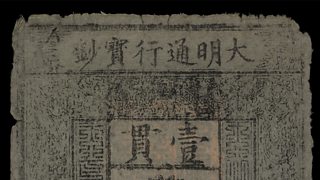

Ming banknote (made around 1400), from China

There's a famous moment in the play of "Peter Pan", when he asks the audience to save Tinkerbell by joining him in believing in fairies - and it's an unfailing winner. That ability to convince others to believe in something they can't see, but wish to be true, is a terrific trick - take the first paper money. Someone in China printed a value on a piece of paper and asked everyone else to agree with them that that paper was actually worth what it said it was. The paper notes, you could say, like the Darling children in "Peter Pan", were supposed to be as good as gold, or in this case as good as copper - literally worth the number of copper coins printed on the note. The whole modern banking system of paper and credit is built on this one simple act of faith - paper money is truly one of the revolutionary inventions of human history.

Today's object is one of those early paper money notes. The Chinese called them "feiqian" - "flying cash" - and the object comes from China at the time of the Ming, around 1400.

"I think the right aphorism is that 'evil was the root of all money'! Money was invented in order to get round the problems of trusting other individuals. But then the question is, could you trust the person who issued the money?" (Mervyn King)

"Here is a note that has managed to, in some sense, stay in circulation for over six centuries - it's extraordinary!" (Timothy Brook)

This week we're circling the world in empires, around five to six hundred years ago, before anybody had in fact physically circled the world. They did know though what made it go round - money and trade were the great drivers of wealth then, as now, and they were essential to the building of empires. Most of the world until this point was exchanging money in coins of gold, silver and copper that had an intrinsic value that you could judge by weight - but the Chinese saw that paper money has obvious advantages over quantities of coin. It's light, it's easily transportable, and it's big enough to carry words and images to announce not only its value but the authority of the government that backs it, and the assumptions on which it rests. Properly managed, paper money is a powerful tool in maintaining an effective state.

At first glance, this note doesn't look at all like modern paper money. It's paper, obviously enough, and it's larger than a sheet of A4. It's a soft, velvety grey colour, and it's made out of mulberry bark, which was the legally approved material for Chinese paper money at the time. The fibres of mulberry bark are long and flexible, so even today, though it's around six hundred years old, this paper is still soft and flexible.

It's fully printed on only one side, a woodblock stamp in black ink, with Chinese characters and decorative features arranged in a series of rows and columns. Along the top, six bold characters announce that this is the "Great Ming Circulating Treasure Certificate". Below this, there is a broad decorative border of dragons going all round the sheet - dragons of course being one of the great symbols of China and of its emperor - and just inside this decorated border are two columns of text, the one on the left announcing again that this is the "Great Ming Treasure Certificate" and the one on the right saying that this is "To Circulate Forever".

That's quite a claim. How permanent can forever be? In stamping that promise on to the very note, the Ming state seems to be asserting that it too will be around forever to honour it. We asked the governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, to comment on this bold assertion:

"Well, I think it's a contract, an implicit contract, between people and the decisions they believe we'll be making in the years and decades to come ... about preserving the value of that money. It is a piece of paper, there's nothing intrinsic in value to it, but its value is determined by the stability of the institutions that lie behind the issuance of that paper money. If people have confidence that those institutions will continue, if they have confidence that their commitment to stability can be believed, then they will accept and use paper money, and it will become a regular and normal part of circulation. And when that breaks down - as it has done in countries where the regime has been destroyed through war or revolution - then the currency collapses."

And indeed, this is exactly what had happened in China around 1350, as the Mongol Empire disintegrated. So one of the great challenges for the new Ming Dynasty, which took over eighteen years later in 1368, was not just to re-order the state, but to re-establish the currency. The first Ming emperor was a rough provincial warlord, Zhu Yuanzhang, who embarked on an ambitious programme to build a Chinese society which would be stable, educated and shaped by the principles of the great philosopher Confucius. Here's the historian Timothy Brook:

"The goal of the founding Ming emperor was that children should be able to read, write and count. He thought literacy was a good idea because it had commercial implications - the economy would run more effectively. It also had moral implications - he wanted school children to read the sayings of Confucius, to read the basic moral texts about filial piety and respecting elders, and he hoped that literacy would accompany the general re-stabilisation of the realm. I would be curious to know how many people could read the banknote, but I would imagine it was ... I'm going to say a quarter of the population could read what's on this note which, by European standards at the time, was remarkable."

As part of this impressive political programme, the new Ming emperor decided to re-launch the paper currency. A sound but flexible monetary system would, he knew, encourage a stable society. So he founded the Imperial Board of Revenue and then, in 1374, a "treasure note control bureau". Paper notes began to be issued the following year. The first challenge was fighting forgery.

All paper currencies run the risk of counterfeiting, because of the enormous gulf between the low real value of the piece of paper, and the high promise value that appears on it, and this Ming note carries on it a government promise of a reward to anyone who denounces a counterfeiter. And alongside this carrot, there was a terrifying stick for any potential forger:

"To counterfeit is death. The informant will receive 250 taels of silver, and in addition the entire property of the criminal."

The much bigger challenge was to keep the worth of the new currency intact. Here, the key monetary decision of the Ming was to ensure that the paper note could always be converted into copper coins - the value of the paper would equal the value of a specific number of coins. Europeans called these coins quite simply "cash" - they're the round coins, with a square hole in the middle, which the Chinese had already been using for well over a thousand years.

One of the things I love about this Ming note is that right in the middle of it is a picture of the actual coins that the paper note represents. There are ten stacks of coins with a hundred in each pile, so a total of one thousand cash or, as it says in writing on the note, one "guan". You can get some idea of just how useful and welcome this early paper money must have been, when you compare carrying the paper around with the actual coins represented. And I have here beside me one thousand cash: five feet (1.5m) of copper coins all on one piece of string! They weigh about seven pounds (about three kilos), they're extremely cumbersome to handle, and very difficult to subdivide and pay out. This note must have made life, for some people, very very much easier.

"Whenever paper money is presented, copper coins will be paid out, and whenever paper money is issued, copper coins will be paid in. This will never prove unworkable. It is like water in a pool."

It sounds easy as can be, doesn't it? But the words "never prove unworkable" would come back to haunt the Ming emperor. As usual, the practice turned out to be more complicated than the theory. The exchange of paper for copper, copper for paper, never flowed smoothly - and like so many governments since, the Ming just couldn't resist the temptation of simply printing more money. The value of the paper money nose-dived, and 15 years after the first Ming banknote was issued, an official noted that a 1,000-cash note like this one had plummeted to an exchange value of a mere 250 copper coins. What had gone wrong? Here's Mervyn King:

"They didn't have a central bank, and they issued too much paper money. It was backed by a copper coin, in principle - you should take this money because it was backed by a copper coin, but in fact that link broke down. And once people realised the link had broken down, then the question of how much it was worth was really a judgement about whether a future administration would issue even more, and devalue its real value in terms of purchasing power. And in the end this money did become worthless because it was over-valued."

This is the first attempt by a state to use paper in such a systematic way, and in the British Museum's collections we've got many many notes from many different countries where that attempt has failed. Is paper money always doomed to failure? Here's Mervyn King again:

"No, I don't think it's always doomed to failure. And I think if you'd asked me four or five years ago, before the financial crisis, I would have said, 'No, I think we've now worked out how to manage paper money'. Perhaps in the light of the financial crisis, we should be a bit more cautious, and maybe if ... to quote Zhou Enlai, another great Chinese figure, when asked about the French Revolution, he said. 'Well, it's too soon to tell'. Maybe we should say about paper money, after seven hundred years, it is perhaps still too soon to tell."

Eventually, around 1425, the Chinese government gave up the struggle and suspended the use of paper money. The fairies had fled, or, in grander language, the faith structure needed for paper money to work had collapsed. Silver bullion would now be the basis of the Ming monetary world. But however difficult it is to manage, paper currency has so many advantages that, inevitably, the world came back to it, and no modern state could now think of functioning without it. And the memory of that paper currency, printed on Chinese mulberry paper, lives on today in a little garden in the middle of London. In the 1920s, the Bank of England, in conscious homage to these paper notes, planted a small stand of mulberry trees.

In the next programme, we'll be with an empire bigger than either the Ottoman or the Ming - the largest on earth at the time - which, in the rarefied air of the High Andes, managed without either writing or money. It's Inca Peru ... embodied in a little gold llama.

-

![]()

Listen to the programme and find out more.