Transplant

Emma’s long wait for a

life-saving call

By Dominic Hughes and Rachael Buchanan

It is the small hours of the morning in the depths of winter, and Emma Watson is sitting in a dimly lit room in Ward 10 of the transplant unit in the Manchester Royal Infirmary.

She looks drawn and tired. It has been a long night.

The previous evening, Emma received a phone call at home to say the moment had come. She has been waiting for a kidney and pancreas transplant for more than a year, and donor organs are on their way to Manchester.

She’s been here before - not once, but a dozen times.

It’s nearly always the same - a phone call, a hurried goodbye to her husband who mostly stays at home to look after their 10-year-old daughter, the dash to the hospital. And then the wait, knowing that she could be just hours away from an operation that has the potential to change her life.

Or, if things go wrong, end it.

But Emma is not the only one on the ward waiting - across the corridor another patient is going through the same process of blood tests, ECGs and health checks.

For each transplant operation, two people on the transplant list are called in. One is a primary recipient, the other a backup. Both are evaluated to establish the best match for the precious organs. Staff do their best to ensure the patients don’t meet.

A transplant could be derailed for many reasons. The donated organs may be in poor condition, they may not suit the recipient, or the patient might have an underlying illness. Something as innocent as a mild cold could be enough to halt the process.

It’s the tail end of 2018, and the last time Emma was on the ward was August. That time, she was carrying too much weight for the operation to go ahead safely. As on previous occasions, hopes had been raised, only to be dashed.

When we meet her, she is downbeat, exhausted, her eyes puffy and smudged with dark rings. Emotionally, she seems flat - wrung-out and resigned.

“When you know you’ve got to go home and carry on living the life you’re living, it’s hard,” she says.

“How long can I carry on like this for? You go home and have a little cry out loud, and then you have one to yourself. You build your hopes up, and then nothing comes out of it.”

Coming to the hospital full of hope, only to be sent home after hours of waiting, disappointed and frustrated, is taking its toll. Emma is on tenterhooks every day, hoping for the call.

“After a year and a half, everyone else gets excited for you. ‘Oh yeah, you’ll get it this time,’ they say. But the more excited you get, the more of a fall you are going to have.”

After all this waiting, will this finally be Emma’s time?

Shortly after 05:00, it is decided who will receive the organs. Once again, it will not be Emma. Her weight is fine, but surgeons have looked at the organs and feel they are a better match for the other patient.

By this time, Emma is dozing on a bed on the ward. Staff decide it is kinder to let her sleep a little while longer, before gently breaking the news to her.

Despite the counselling patients receive, and the compassion of the staff who have to break the bad news, it’s tough to take.

“You just think, ‘Back to square one, start all over again.’ And then you think, ‘Can I do this again? Can I keep doing this?’”

Emma’s wait for a suitable donor continues, but the strain is becoming unbearable. And all the time the 38-year-old’s health is slowly failing. Her kidney function - a measure of how her organs are coping - is about just 7%.

Time is running out.

It’s the tail end of 2018, and the last time Emma was on the ward was August. That time, she was carrying too much weight for the operation to go ahead safely. As on previous occasions, hopes had been raised - only to be dashed.

When we meet her, she is downbeat, exhausted, her eyes puffy and smudged with dark rings. Emotionally, she seems flat - wrung-out and resigned.

“When you know you’ve got to go home and carry on living the life you’re living, it’s hard,” she says.

“How long can I carry on like this for? You go home and have a little cry out loud, and then you have one to yourself. You build your hopes up, and then nothing comes out of it.”

Coming to the hospital full of hope, only to be sent home after hours of waiting, disappointed and frustrated, is taking its toll. Emma is on tenterhooks every day, hoping for the call.

“After a year and a half, everyone else gets excited for you. ‘Oh yeah, you’ll get it this time,’ they say. I think the more excited you get, the more of a fall you are going to have.

After all this waiting, will this finally be Emma’s time?

Shortly after 05:00, it is decided who will receive the organs. Once again, it will not be Emma. Her weight is fine but the surgeons have looked at the organs and feel they are a better match for the other patient.

By this time, Emma is dozing on a bed in the ward. The staff decide it is kinder to let her sleep a little while longer before gently breaking the news to her.

Despite the counselling patients receive, and the compassion of the staff who have to break the bad news, it’s tough to take.

“You just think, ‘Back to square one, start all over again.’ And then you think, ‘Can I do this again? Can I keep doing this?’”

Emma’s wait for a suitable donor continues but the strain is becoming unbearable. And all the time the 38-year-old’s health is slowly failing. Her kidney function - a measure of how her organs are coping - is about just 7%.

Time is running out.

The machine at home

Emma has type 1 diabetes.

About 8% of people in the UK with diabetes have type 1.

She was first diagnosed at the age of 10, the age her daughter is now. Emma had been feeling unwell but when her mother phoned the family doctor, she was told it was probably just a bug.

“It got to the third day and I was very poorly.”

Emma’s blood-sugar levels had soared, and when the doctor came out to see her, he said she needed to go to hospital straight away.

“In the space of a couple of weeks, I lost a couple of stone in hospital and the doctor said I was close to being in a coma.”

That was the beginning of a life that would eventually be dominated by type 1 diabetes.

It’s a condition that is not caused by diet or lifestyle, and despite years of research, it is still not clear why it happens. But it has a profound effect on the lives of those who have it.

After being diagnosed, Emma needed to take insulin and to be very careful about what she ate, and when. And like many of those diagnosed not far off their teenage years, it was a real struggle.

“You want to do what everyone else is doing. You want to go out, you want to enjoy life. You don’t tend to think, ‘I need to get up, I need to take my insulin, I need to eat the right food.’ That’s the last thing on your mind. You want to fit in.”

With type 1, the body attacks the cells in the pancreas that produce insulin, the hormone that allows glucose in our blood to enter our body’s cells and provide us with fuel.

The body still breaks down the carbohydrates in food and drink to glucose - or sugars - which enter the bloodstream, but in the absence of insulin these sugars have nowhere to go. The glucose builds up and over a prolonged period can damage the heart, eyes, feet and kidneys.

By the time she reached her 20s, Emma was struggling. Her eyesight was affected and her weight had shot up to about 19 stone (121kg). Perhaps most seriously, her kidneys were under pressure, compounded by a series of infections.

A gastric bypass helped get her weight under control and eased the strain on her kidneys, but gradually their performance started to deteriorate once again.

Emma’s kidneys were in a bad way by the time she was in her late 30s. But with type 1 diabetes, simply having a kidney transplant would be only a temporary measure. She needed a new pancreas as well, so that her body could start producing the insulin it needed on its own. Without the pancreas, any new kidneys would just become damaged in the same way.

Emma manages to hold down a 40-hour-a-week job as an office administrator, despite the gruelling process of dialysis that now dominates her life.

She started doing what is known as peritoneal dialysis in May 2017. It’s a process that helps her failing kidneys flush out the waste products from her body.

It involves her attaching a tube to a valve fitted in her stomach wall. The tube is then attached to a machine that pumps fluid into her stomach, causing it to swell up.

“You feel your stomach getting bigger and bigger, because your peritoneal cavity is at the front of your stomach.”

It makes moving around uncomfortable and sleeping difficult, she says.

“It’s like you’ve eaten too much and you can’t move. You’ve got to try to sleep with that feeling. [Then] it drains out and starts again. You’ll have that feeling all night.”

The fluid is then flushed out through another hose that trails across her bedroom floor and into the bathroom, where it empties into the toilet. The process is repeated four or five times a night - 10 litres of fluid altogether.

There is also a lot of infection control that needs to be done. Everything has to be cleaned with anti-bacterial wipes to make sure no germs get introduced.

The machine makes a swooshing sound as it flushes the fluid in and out of Emma’s body. It will often sound an alarm during the night - if the hose gets a kink when Emma rolls over in her sleep, for example. It is an exhausting process.

“I can’t remember the last time I had a decent night’s sleep,” says Emma.

“And then sometimes you just sit down and shout. And you’re like, ‘I’m shouting at a machine.’ You just get so annoyed with it. It just goes on and on.”

There are also significant logistical challenges to carrying out dialysis at home. Emma must make sure she has adequate stocks of all the fluid packs, sterile wipes and other bits of kit that she uses every night.

In her new-build house on a modern estate in Cheshire, an entire room is given over to storing the things she needs. But without dialysis, her kidneys will fail.

Emma relies heavily on her husband Lee to do the washing, cleaning and cooking. Her brother and sister are also available to help out.

She does, however, try to do the school run in the morning before going to work - even though it means waking up really early to allow the fluid to drain from her body first.

“My daughter’s been late a couple of times because I’ve just been stuck on my machine.”

After a day at work, fighting off exhaustion, Emma struggles to fit in any family time.

“I pick my daughter up, come back home and then go to bed for about four hours. Then I’ll get up for about an hour. I’ll prepare my machine and then I will plug up and I’ll go back to sleep. Some nights I may sit up for a couple of hours.”

Emma worries that managing her condition means that her daughter is missing out on things. But there is a deeper, nagging anxiety - that her daughter might have inherited diabetes.

“My niece got it when she was 10, so it seems to be hereditary. You do think, ‘Is my child going to get this?’ I’ve always tried to keep her active. And you do try to push [the message], ‘Treat your body well, so you don’t end up like your mum.’”

The dialysis, the phone calls, the waiting, the gnawing worry over her daughter. There is no escape.

“I think I’m just existing. I’m not living. And it does get soul destroying, doing it day in and day out.”

Dialysis will keep Emma going, but she is running out of road. Kidneys that are functioning at just 7% are not a long-term option. On average, a 35-year-old with diabetes and kidney failure stands to see their life shortened by about 25 years.

Emma needs that transplant.

Finding a match

We first met Emma on a bright autumn afternoon in November 2017, when she had been on the organ transplant waiting list for just three months. At the time, she was one of 175 people in the UK waiting for both a pancreas and kidney. But they are just a small element of the wider UK organ waiting list.

Each year about 6,000 people have their lives put on hold for want of a replacement heart, kidney, liver, lungs or bowel.

Patients like Emma - who need a simultaneous kidney and pancreas transplant - have an average wait of just under a year. For those needing other organs, it can be much longer - an average of 706 days for a kidney and 1,085 for a non-urgent heart transplant - and many don’t make it.

About 400 people die each year while waiting for an organ, with more than 700 a year taken off the list because they are no longer well enough for a transplant.

So with more patients in need than organs on offer, how is the decision made to give those life-saving donations?

It’s not just the people who have waited the longest. A range of complex medical and biological factors weigh in, most notably regarding the body’s immune system.

Its job is to seek out and destroy foreign organisms - a welcome function when talking about bacteria or other pathogens, but a problem when an organ is being transferred from one person into another.

The key to a successful transplant is finding a donor who is as biologically similar to the recipient as possible. Crucial to that match is a collection of markers on the outside of nearly all of our cells - HLAs (Human Leukocyte Antigens).

They are like little flags that tell our immune systems which cells belong in our bodies and which don’t. An identical line-up of HLAs is extremely unlikely, but in kidney transplants, for example, doctors like to match at least a third of the key HLAs to be more confident of success.

When Emma joined the transplant list, her blood group and HLA profile were put on file.

Since then, every time a kidney and pancreas was donated, the blood group and HLA profile of the donor were compared to Emma’s.

This and other factors - such as time on the waiting list, age difference between the donor and recipient, the rarity of HLA profile, and whether a patient’s immune system has developed antibodies to certain tissue types - all form part of the regularly revised algorithm that is used to match donor to recipient.

When a new organ becomes available, the UK transplant computer system, rather than a human, combs through all those data points to produce the closest, and fairest, match.

That search takes in the whole of the UK, which means organs could be matched to patients anywhere in the four nations, even though there are differences in the way donation systems operate.

Wales and Jersey have moved to an opt-out system, which means everyone is presumed to be a donor unless they state on the register that they don’t want to donate. Elsewhere, there is an opt-in system – people need to sign the organ donor register if they want to donate.

But England and Scotland will also switch this year, and Guernsey and the Isle of Man have plans to follow later. Northern Ireland is sticking to opt-in.

The jury is still out on whether this move to what is sometimes called “presumed consent” will increase the number of organs available for transplant, as families will still have the last word on whether donation goes ahead.

But the disparity in the maths is clear - with about 6,000 patients on the waiting list and just 3,941 transplants from UK deceased donors going ahead in 2018, there are not enough donors to meet the need.

A key factor is whether a person dies in circumstances suitable for donation.

It is a common misconception that someone can be a donor regardless of how they die, for example at the side of the road in a traffic accident. Because of the fragility of our organs, death needs to have occurred in a controlled environment.

As soon as a heart stops beating, blood and oxygen cease circulating around the body and its organs begin to deteriorate.

For a kidney, ideally there is a window of up to 18 hours to remove the organ from the donor, transport it and transplant it into the recipient. For the heart it is just four hours.

So, every donor will have been on an intensive care unit.

For about 40% of patients, death will come when their heart has stopped beating - following either cardiac arrest or a planned withdrawal of life support. But most donations are from patients who are “brain-dead” - having suffered such a severe injury to their brain that they have permanently lost the potential for consciousness and the capacity to breathe on their own.

A series of tests is carried out over 30 minutes - often in front of the family - to confirm the diagnosis. They include shining a light in the donor’s eyes, trying to induce a gag reflex, and seeing whether they are able to breathe unaided. Brain death is confirmed if the patient fails to respond to all of these tests.

Only about 1% of the 600,000 people who die each year in the UK do so under conditions that would enable the organs to be used. The pool is already small, but if you add in lack of awareness about the dying patient’s wishes, the numbers shrink further.

Donating a loved one’s organs - NHS intensive care staff show the 成人快手 the test for brain stem death and how families are approached for organ donation

Under all UK laws, families have the final say on donation. Fewer than half consent if they are unaware of their deceased relative’s views. Nine in 10 agree to donate when they know it was what the person wanted.

There are concerns among medics and patient groups that the change to the new system, where a patient is presumed to have consented, could foster the belief that there is no need to sign the organ donation register, leaving even more families uncertain of their relative’s wishes.

The organisation in charge of organ donation - NHS Blood and Transplant - is clear that if you want to donate, it is vital you sign the register and share your wishes with your family.

The personal touch

The renal transplant unit at the Manchester Royal Infirmary is the busiest in the country, with more operations than any other hospital in the UK.

At the heart of the process is a relatively small team of transplant co-ordinators. All are experienced nurses and they act as the bridge between the patients and the hospital.

One of them is Brian Kelly, a 42-year-old softly spoken Irishman who radiates a kind of calm compassion. It is he, or one of his colleagues, who will phone patients like Emma and let them know that a potential donor has been identified and that they should come into hospital.

They are also often the ones who have to tell them when a transplant is not going ahead. But Brian says it helps that each patient is given counselling when they go on the transplant list.

“It’s actually OK, because we’ve pre-empted everything. When I call somebody on the phone, I always say there’s a ‘potential’ offer, and this may be a dry run.”

Brian says that when a patient is called in and then sent home, it increases their chances of getting another call soon.

The MRI has about 900 people on its transplant list, most of whom are waiting for a single kidney rather than the dual transplant Emma needs. Only 500 or so are what is called “active”.

Some patients may be on holiday, others may need a break for personal or health reasons. But every day there are fresh cases to manage.

It may come as a surprise to know that some patients will receive more than one transplant over the course of a lifetime.

Brian, who has been working with the team for more than a decade, says that while some patients have kidneys that have lasted 30 years or more, the average is only 10 to 12 years. So he is beginning to see patients who he cared for when he first started on the post-operative ward.

For Brian, what matters even more than all the logistics that he carries out every day, is that human contact with patients. But there is always the knowledge that some may not make it.

“It’s very depressing sometimes. A couple of young people recently passed away while waiting on the list. And someone came around for another transplant - a woman in her 30s. We knew the family, we saw her here for her first transplant, and unfortunately she passed away.

“But [there have been] more highs than lows, without a doubt. Over the past 10 years, I have seen many people who have done so, so well, and who recognise and appreciate what we’ve done.

“I think about the donors, as well. They’re not all people that have led very full lives. A lot of them are very young, and you are just very grateful.”

‘A beautiful operation’

It’s a curious thing but most transplants seem to take place at night, or at least in the early hours of the morning.

We are told this is when the operating theatres are most likely to be free for what can be long and complicated procedures.

Just 10 days after Emma was last called in, only to be sent home again, she is back at the MRI on another cold, dark winter’s night.

Once more she has packed a bag, said goodbye to Lee and her daughter, and headed off alone, unsure of what lies ahead. This is the 14th time she has been called with news of a potential donor.

In contrast to the last time she was here, she is brighter and definitely more upbeat. Blood tests are under way to make sure she is in good health.

There is a feeling that this time, things may be moving in the right direction.

And soon the news Emma has been waiting for comes.

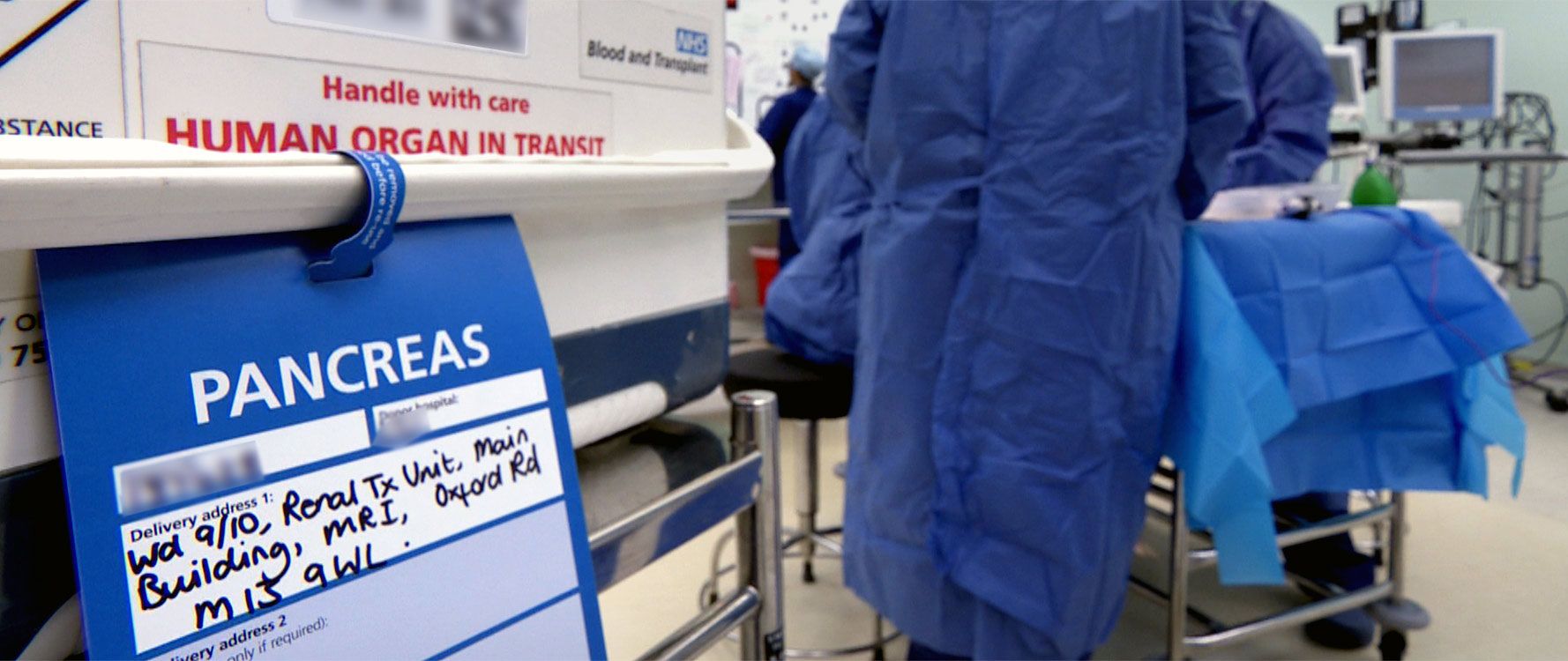

Out there in the darkness, an ambulance is making its way through the rain towards Manchester, carrying with it a precious cargo of donor organs.

At about 04:20 they arrive, the flashing blue light of the ambulance illuminating an otherwise deserted, rainswept hospital forecourt. The organs are taken quickly up to the transplant unit in what looks like a cool box. Forms are signed and the organs officially checked in at 04:26.

There are still a few hurdles to clear. The surgical team needs to be sure that the organs are a good match for Emma. Doctors also want to have a good look at the state they are in.

Nearly two hours are spent delicately examining and repairing the kidney and pancreas. Extracting them from the donor can cause some damage. This time, there is intricate stitching to be done.

Each organ sits in fluid in a shallow bowl, bathed by a pool of light from the bright surgical lamps that hang from the ceiling. Three doctors are hunched over them, talking to each other in low, controlled voices.

The whole procedure is overseen by consultant surgeon Raman Dhanda, who has been working for more than 15 years in transplant surgery.

He feels the pancreas is the biggest cause for concern.

“It has quite a complex blood supply and we have to ensure that there’s no damage, and the blood vessels are properly reconstructed,” he says.

“It’s a delicate organ by nature, so the main risk with the pancreas is the development of inflammation, a condition called pancreatitis. The more you touch it, the more likely the patient is going to get pancreatitis.

“So we try not to touch it, but at the same time prepare it in a way that there are the fewest risk factors associated with the organs themselves.”

There is less demand for the pancreas than other organs. The waiting list is one of the shorter ones, with just 250 people as of April 2019. So with nearly 500 pancreases donated each year, you would expect the list to be cleared pretty quickly.

But given how easily damaged it can become, more than half never make it into a patient. This means just 204 organs were transplanted in 2018, while about the same number of new patients joined the queue.

Most people know what to expect when they see a kidney. Human kidneys are not that different, at least in external appearance, from those you might see in a butcher’s window. The pancreas resembles what you might imagine an alien from another world could look like – vaguely triangular, sort of ruffled around the edges, slightly bobbly, a creamy grey colour as it sits in its bowl of fluid.

Eventually Dhanda is satisfied and the news is good. The organs look healthy. Emma is prepped for surgery.

It’s just after 06:00 when she goes into the operating theatre. Two anaesthetists check Emma’s vital signs to make sure she is unconscious but stable. Dhanda is there with two surgeon colleagues.

Emma has been warned there is a risk she may not survive the surgery if something goes wrong. But the team is confident, calm, efficient.

Surgeons begin what will turn out to be an operation lasting more than four and a half hours. The first incision into Emma’s abdomen is made at about 07:45.

The whole procedure is overseen by consultant surgeon Raman Dhanda, who has more than 15 years of experience in transplant surgery.

He feels the pancreas is the biggest cause for concern.

“It has quite a complex blood supply and we have to ensure that there’s no damage and the blood vessels are properly reconstructed,” he says.

“It’s a delicate organ by nature, so the main risk with the pancreas is the development of inflammation, a condition called pancreatitis. The more you touch it, the more likely the patient is going to get pancreatitis.

“So we try not to touch the pancreas, but at the same time prepare it in a way that there are fewest risk factors associated with the organs themselves.”

There is less demand for the pancreas than other organs. The waiting list is one of the shorter ones, with just 250 people as of April 2019. So with nearly 500 pancreases donated each year, you would expect the list to be cleared pretty quickly.

But given how easily damaged it can become, more than half never make it into a patient. This means just 204 organs were transplanted in 2018, while the same number of new patients joined the queue.

Most people know what to expect when they see a kidney. Human kidneys are not that different, at least in external appearance, from those you might see in a butcher’s window. The pancreas resembles what you might imagine an alien from another world could look like – vaguely triangular, sort of ruffled around the edges, slightly bobbly, a creamy grey colour as it sits in its bowl of fluid.

Eventually Dhanda is satisfied and the news is good. The organs look healthy. Emma is prepped for surgery.

It’s just after 06:00 when she goes into the operating theatre. Two anaesthetists check Emma’s vital signs to make sure she is unconscious but stable. Dhanda is there with two surgeon colleagues.

Emma has been warned there is a risk she may not survive the surgery if something goes wrong. But the team is confident, calm, efficient.

Surgeons begin what will turn out to be an operation lasting more than four and a half hours. The first incision into Emma’s abdomen is made at about 07:45.

“This operation is one of the most beautiful operations we can actually perform because it’s very different from other surgeries. Here you are giving something to the patient.”

“This operation is one of the most beautiful operations we can actually perform because it’s very different from other surgeries. Here you are giving something to the patient.”

“It’s a complex operation,” says Dhanda. “But it’s enjoyable because it needs a lot of surgical skills. Most of the time whilst you’re doing the operation, you’re just thinking about the benefit the patient is going to get straight away.

“I’m very passionate about it. This operation is one of the most beautiful operations we can actually perform because it’s very different from other surgeries. You are giving something to the patient, rather than removing abnormal or pathological organs from a patient. At the time you’re just concentrating on getting the pancreas in right, as quickly as possible.”

The new organs will sit in the body alongside Emma’s existing ones. It takes a few hours to get to the point when they can be transplanted.

First, the pancreas goes in, lifted carefully from its bed of ice. The tension in the room rises. This is a crucial moment. If the pancreas retains its creamy grey colour, something has gone wrong.

There is palpable relief when, at about 09:20, the pancreas quickly turns a rosy pink, showing that blood is flowing through the organ as it should.

“It’s a complex operation,” says Dhanda. “But it’s quite an enjoyable because it needs a lot of surgical skills. Most of the time whilst you’re doing the operation you’re just thinking about the benefit the patient is going to get straight away.

“I’m very passionate about it. This operation is one of the most beautiful operations we can actually perform because it’s very different from other surgeries. You are giving something to the patient, rather than removing abnormal or pathological organs from a patient. At the time you’re just concentrating on getting the pancreas in right, as quickly as possible.”

The new organs will sit in the body alongside Emma’s existing ones. It takes a few hours to get to the point when they can be transplanted.

First, the pancreas goes in, lifted carefully from its bed of ice. The tension in the room rises. This is a crucial moment. If the pancreas retains its creamy grey colour, something has gone wrong.

There is palpable relief when, at about 09:20, the pancreas quickly turns a rosy pink, showing that blood is flowing through the organ as it should.

Dhanda is pleased.

“The patient is not requiring any insulin. The blood sugars are already falling. We would like [the pancreas] to be salmon pink, which you can see it is, so you can see it is functioning really well.”

The kidney is transplanted next. It will be a few hours before the operation is complete and Emma is taken to the intensive care unit, where she will spend several days recovering.

While the operation itself was a success, Emma experiences some complications.

The new kidney is a bit reluctant to start working properly and there is a suspected bleed in her abdomen that involves a second investigative operation.

She spends much longer in hospital than was originally expected and her recovery is long and slow. But essentially she has been cured - at least for the moment - of the type 1 diabetes that has plagued her life for nearly 20 years.

‘I can live my life rather than just exist’

We catch up with Emma in the spring of 2019 in a park near her house. Although she is still recovering and is moving a little gingerly, the change in her is immediately obvious.

“It’s been a long recovery,” she says. “But every day it has got better. Like any big operation, it’s a shock to the system. But in the long term, it’s going to be worth it.”

And the diabetes is now a thing of the past, although it has left her with a legacy of poor eyesight and problems with her feet. As long as her new pancreas lasts, Emma can live a much more normal life.

“I do feel like somebody that isn’t diabetic. Obviously, I’ve got complications that are hard because of the diabetes. Hopefully, I should get at least 10 years out of it. But sometimes things do last longer, sometimes shorter.”

Emma will have to take immunosuppressants - drugs to ensure her body doesn’t reject the transplanted organs - for the rest of her life.

But so far, things are going well. She is gradually picking up the threads of her life and has been thinking about doing some of the things that her condition had made impossible.

When we first met in 2017, one of the things that obviously weighed heavily on Emma was the impact on her family. So what about now?

“I’ve got plans. I’d like to go on holiday and just live my life, instead of just existing. So now there’s nothing to stop me doing anything that I want to do - holidays, further my career, do something that I’ve not been able to do.

“I want more time with my daughter. I can take her for her dance exams and things like that, which I wasn’t doing before.”

Emma still needs to be careful about what she eats. Her body is relying on one new kidney, and it is possible that her kidney function will start to decline again.

Her gratitude to the team in Manchester is genuine and heartfelt.

“They’ve definitely done a fantastic job. They’ve been there for me. I can’t fault them at all. They are such a lovely team. And very, very supportive.”

But there is also the selfless decision by one donor and their family. That person’s death gave Emma the gift of a new life. She doesn’t know who that person was, but the hospital provides support to transplant patients so they can write to the donors’ families to express their gratitude. So does she think about them?

“Oh God, of course I do. It’s a grieving process, obviously, for the donor’s family. When you’re in that situation and you’ve lost somebody, it’s hard to think about organ donation.”

Emma will be living with the consequences of the transplant for years to come. But if it wasn’t for the donor whose life ended prematurely, Emma’s story would also have been over far too soon.

Credits:

Authors: Dominic Hughes and Rachael Buchanan

Online production: Paul Kerley

Photography: Emma Lynch

Graphics: Joy Roxas

Video: Phillip Edwards, Stephen Fildes, Brijesh Patel and Paul Walker

Additional images: Getty Images, Alamy

Editor: Kathryn Westcott

With thanks to:

The staff at Manchester Royal Infirmary Renal Transplant Unit - particularly Brian Kelly, Lorraine McClean, Afshin Tavakoli and Raman Dhanda

More long reads:

The battle to separate Safa and Marwa

Why was our son left starving for five days?