Our son’s final days

‘It was like he didn’t matter’

By Sophie Hutchinson

NHS investigators are to meet the family of a young, autistic man - left starving and desperately thirsty in hospital while waiting for a delayed operation.

Mark Stuart spent five days in agony and died following a catalogue of failings by NHS staff. His parents say they have been battling for answers for four years.

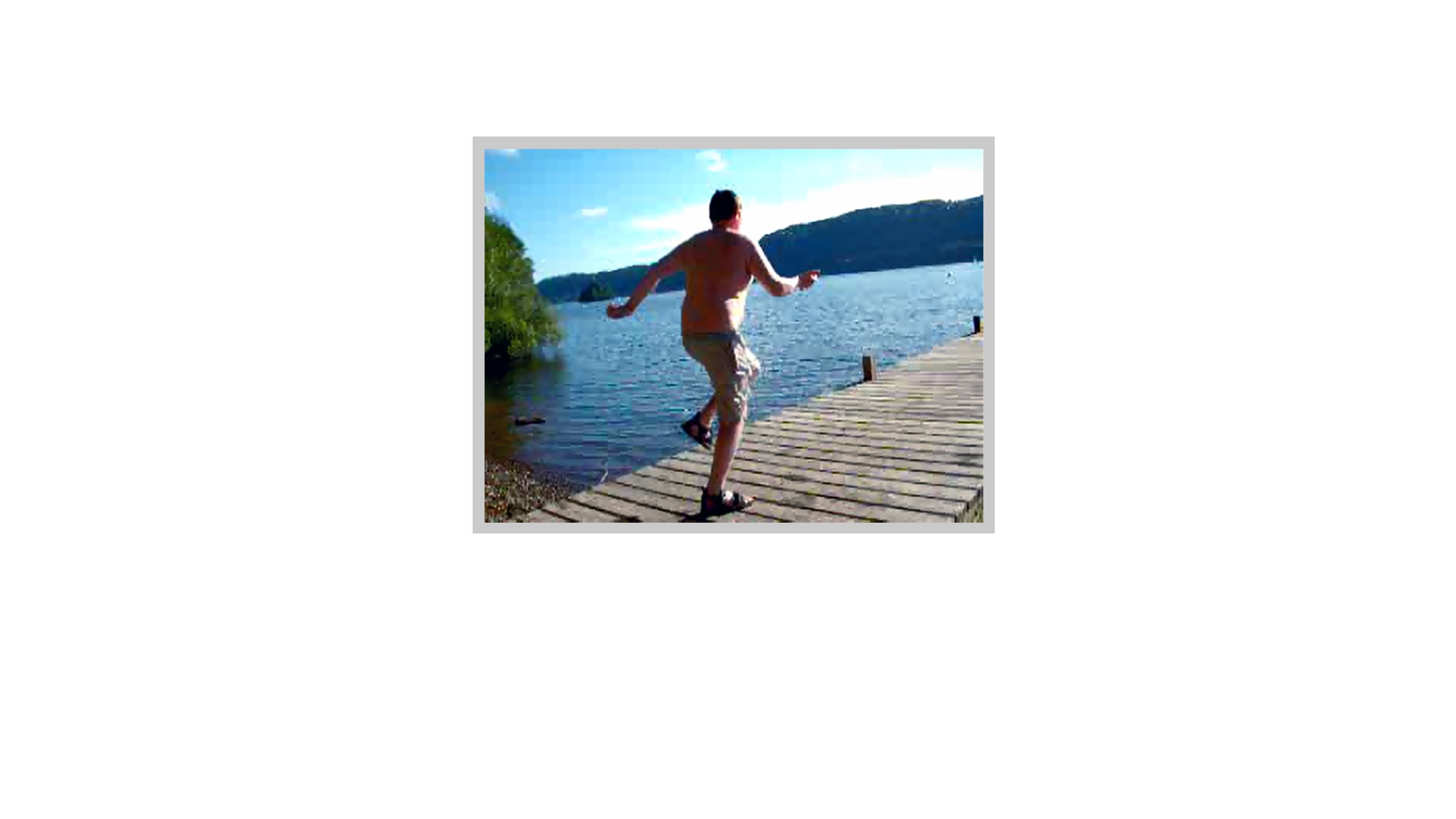

“I feel so guilty that I didn’t raise the roof," says Mark Stuart's father Richard. “I just sit on the end of the jetty and say, ‘I’m sorry Mark.’"

It’s four years since Richard and Janet Stuart scattered their son’s ashes at his favourite swimming spot at Windermere, Cumbria.

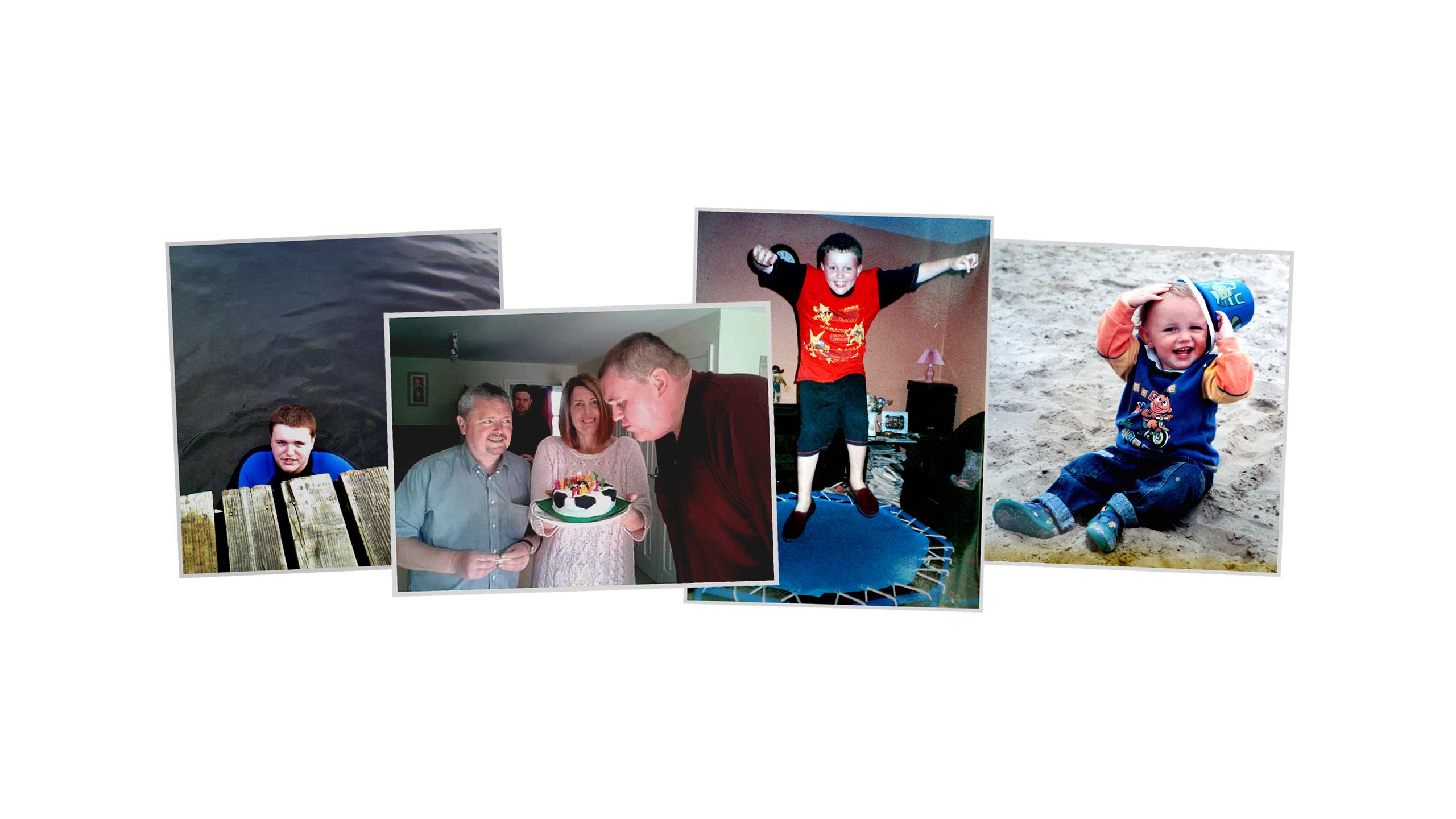

Mark had a passion for open-water swimming. He had lived most of his life with his parents in the grey-stone town of Kendal on the edge of the Lake District. As a result he could boast that he had swum in all the lakes there. His favourite spot was at Millerground, on the eastern shore of Lake Windermere, where he would go most days during the summer. He loved running along the jetty and jumping in.

His family say it was like having a huge, open-air swimming pool on their doorstep.

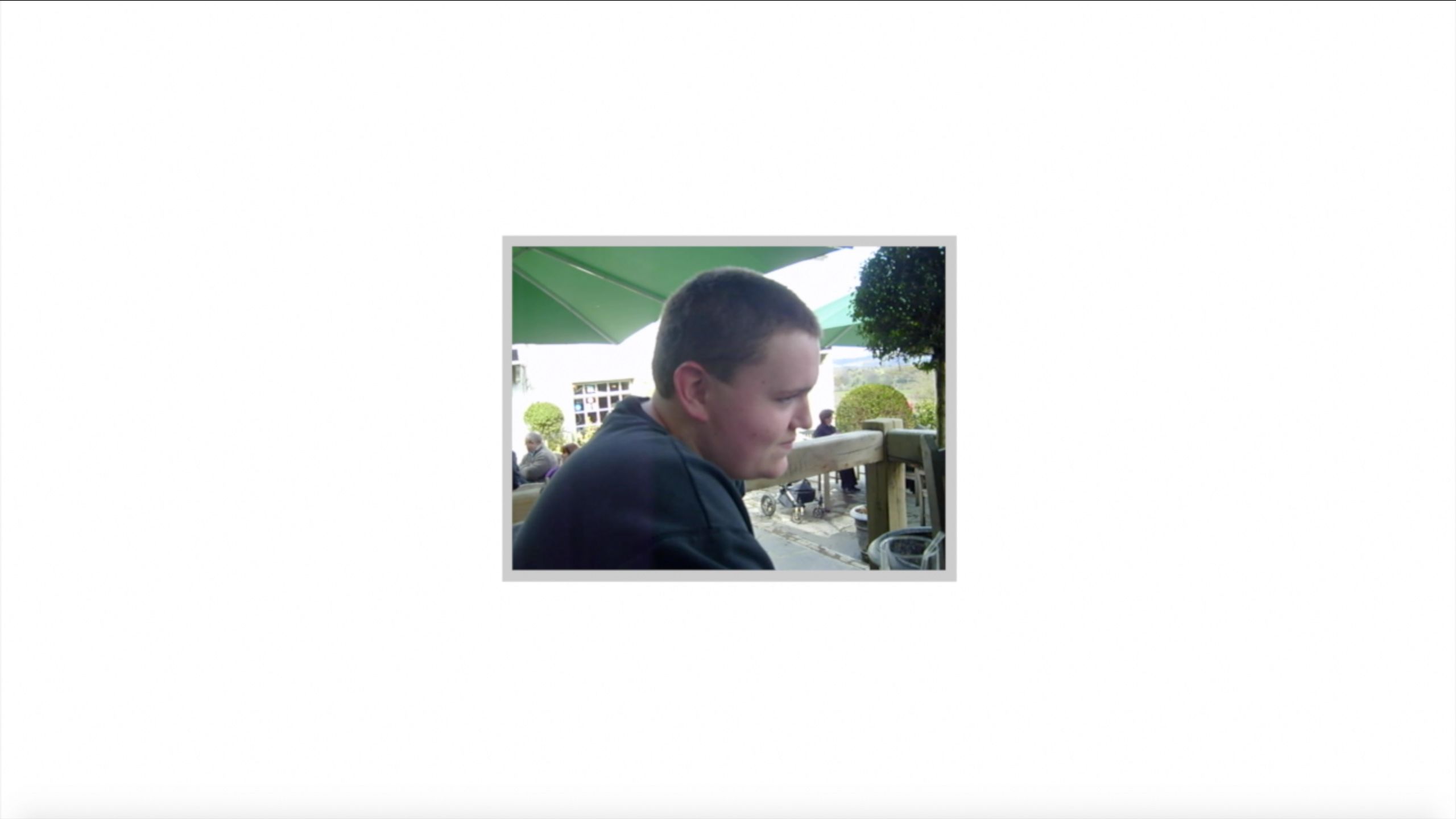

Like his father, Mark was autistic and highly intelligent, but unlike his father, Mark’s obsession for detail could be overwhelming. His mother says the family didn’t need a satnav on holiday because Mark had memorised the entire national motorway network, including every junction.

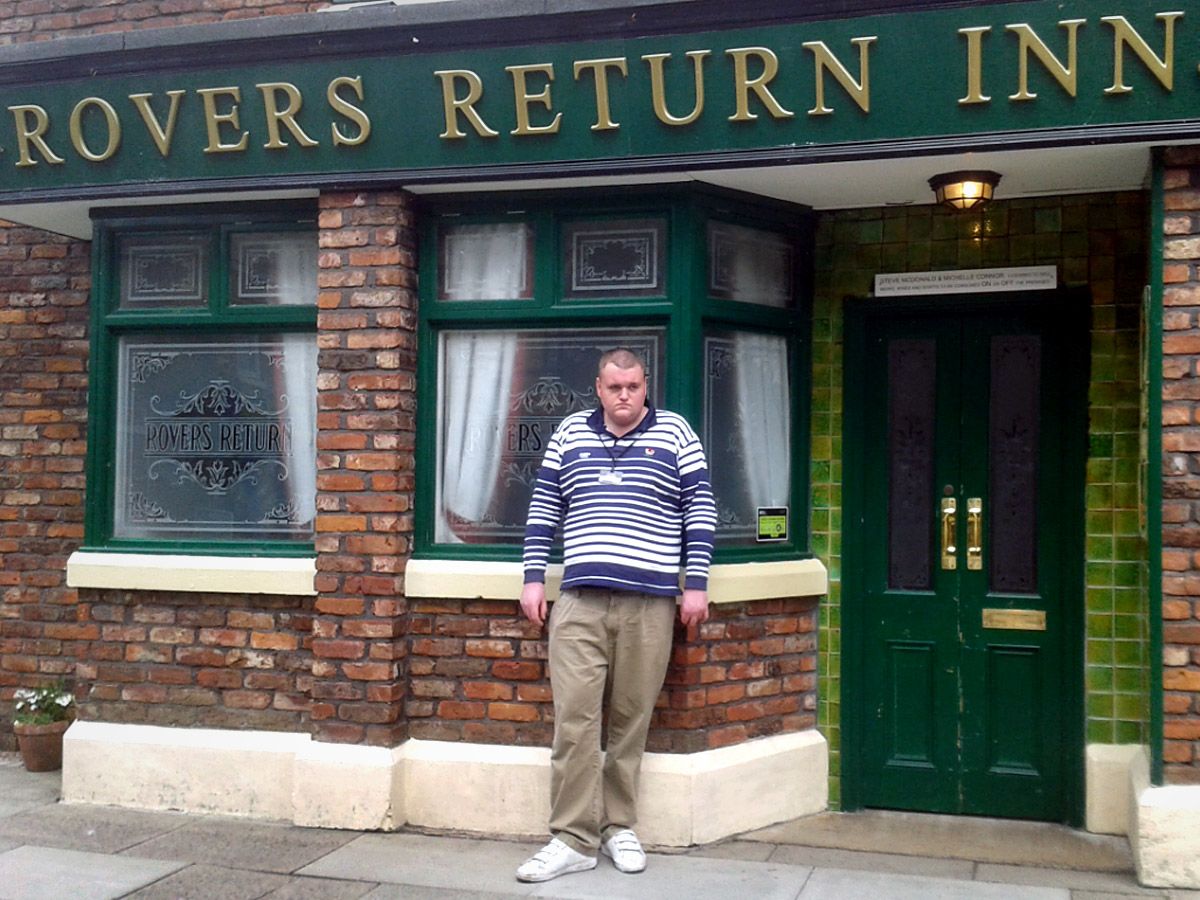

Television and films were also a great love - he would record episodes of Coronation Street and watch them again and again.

As a young boy, Mark had been full of life, even exuberant, but as a teenager his autism became more pronounced and he was increasingly afraid of speaking to people. At 6ft 7in, to some people he was a giant of a man, but in the year he died - aged 22 - he was only just gaining enough confidence to make his first friends.

This new-found social potential would never be realised. Mark developed problems with his digestive system and was in and out of his local hospital.

He had an operation to create a hole, or stoma, in his stomach so that the food waste could leave his body more easily. This led to further problems, however, because the food seemed to pass through him undigested. Mark suddenly started losing serious amounts of weight.

In the six months before he died, he lost a staggering seven stone - a third of his body weight.

Eventually Mark’s stoma had to be reversed, but then his bowel became blocked. He developed an agonising stomach ache, accompanied by vomiting and diarrhoea.

On an autumn night in 2015, things got much worse for Mark.

“I feel so guilty that I didn’t raise the roof," says Mark Stuart's father Richard. “I just sit on the end of the jetty and say, ‘I’m sorry Mark.’"

It’s four years since Richard and Janet Stuart scattered their son’s ashes at his favourite swimming spot at Windermere, Cumbria.

Mark had a passion for open-water swimming. He had lived most of his life with his parents in the grey-stone town of Kendal on the edge of the Lake District. As a result he could boast that he had swum in all the lakes there. His favourite spot was at Millerground, on the eastern shore of Lake Windermere, where he would go most days during the summer. He loved running along the jetty and jumping in.

His family say it was like having a huge, open-air swimming pool on their doorstep.

Like his father, Mark was autistic and highly intelligent, but unlike his father, Mark’s obsession for detail could be overwhelming. His mother says the family didn’t need a satnav on holiday because Mark had memorised the entire national motorway network, including every junction.

Television and films were also a great love - he would record episodes of Coronation Street and watch them again and again.

As a young boy, Mark had been full of life, even exuberant, but as a teenager his autism became more pronounced and he was increasingly afraid of speaking to people. At 6ft 7in, to some people he was a giant of a man, but in the year he died - aged 22 - he was only just gaining enough confidence to make his first friends.

This new-found social potential would never be realised. Mark developed problems with his digestive system and was in and out of his local hospital.

He had an operation to create a hole, or stoma, in his stomach so that the food waste could leave his body more easily. This led to further problems, however, because the food seemed to pass through him undigested. Mark suddenly started losing serious amounts of weight.

In the six months before he died, he lost a staggering seven stone - a third of his body weight.

Eventually Mark’s stoma had to be reversed, but then his bowel became blocked. He developed an agonising stomach ache, accompanied by vomiting and diarrhoea.

On an autumn night in 2015, things got much worse for Mark.

Five days in hospital

9 - 13 November 2015

Monday

In the early hours of the morning, Mark’s mother rushed him to the Royal Blackburn Hospital - about an hour’s drive from home. It wasn’t their local hospital but they chose it because Mark had a planned appointment with a specialist bowel doctor there later that week.

06:12

Mark arrived at A&E in severe pain. He was being sick and had an extremely bloated stomach.

His medical notes from the week before indicated he was so malnourished that he was at risk of Refeeding Syndrome - when too much food taken into the body too quickly can lead to a fatal shock.

Mark was starving and in desperate need of carefully prescribed nutrients, but staff failed to take this into account.

07:30

An X-ray confirmed Mark had a partial bowel blockage.

09:00

To try to relieve pressure on Mark’s stomach, nurses used a tube to draw a pint and a half (800mls) of backed up, intestinal fluid out of his stomach.

His parents remember a nurse saying: “No wonder you were in pain Mark.”

But while this gave him some short-term relief, Mark’s bowel was still blocked. He continued to have episodes of pain all day - they were so severe that he required morphine.

He was at risk of dehydration because he was regularly vomiting and had diarrhoea. At this point he hadn’t eaten anything for 12 hours.

The doctors’ orders were that he should be “nil by mouth”.

He was hooked up to a drip, which meant he could be given vital fluids and - if appropriate - nutrition, directly into his bloodstream.

A blood test indicated possible sepsis, which is a dangerous overreaction by the body’s immune system to an infection. He was prescribed antibiotics.

- Nil by mouth

- No intravenous nutrition

- Mark received a basic three-litre dose of intravenous fluid, which didn’t take into account his increased risk of dehydration because of vomiting and diarrhoea

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) recommends a fluid maintenance dose of 2.5 - 3 litres a day, but more is required if there is significant fluid loss.

Tuesday

Mark had now been in hospital for 24 hours with no nutrition and no extra fluids to make up for his diarrhoea and vomiting. He was extremely thirsty.

He was on an acute surgical ward in his own room, because his parents needed to be with him at all times to help him communicate. He continued to be in severe pain.

During the morning ward round, Mark’s mother Janet says the consultant commented on his “alarming weight loss and unwell state”.

By early evening, a surgeon had visited and set out three options for surgery.

The family didn’t know how to choose and felt confused. They asked the surgeon about Mark’s lack of nutrition and claim he replied curtly, “Of course he can’t eat, he has a bowel obstruction.”

- Nil by mouth

- No intravenous nutrition

- One litre of intravenous fluid, far below the recommended basic daily dose of 2.5 to 3 litres and that’s without the extra needed for Mark’s considerable fluid loss

Wednesday

Forty-eight hours in, and Mark had been given no nutrition and very limited fluids. He was starving and desperately thirsty. It was a busy hospital ward but no-one seemed to have realised the gravity of his condition.

A third consultant visited Mark. The medical opinion was that he should have a colostomy. His parents voiced their concerns that their son might not be well enough to undergo an operation.

11:00

The same consultant decided Mark’s condition was not acute and placed him on the operating list for the next day.

Mark was in severe and increasing pain throughout the evening.

- Nil by mouth

- No intravenous nutrition

- One litre of intravenous fluid

Thursday

By now Mark had gone more than 72 hours without nutrition, and for nearly 20 hours he didn’t receive any fluid at all, according to his patient records. In addition, nobody was taking into consideration or monitoring his considerable fluid loss.

Mark was desperately thirsty and starving. His lips were dry and flaky, his parents say. They explained again and again to their son that he couldn’t have a drink because he was about to have an operation.

As his pain escalated, Mark became increasingly anxious and desperate for the operation. He was supposed to be third on the list that day.

Janet says her son sat on his bedside chair all day wearing his operating gown, waiting to go to theatre. But nothing happened.

She and Richard put all their energy into reassuring Mark that everything would be alright and keeping him calm.

18:20

Doctors informed the family that the plans for surgery had changed and that Mark would have an operation using a stent - a tiny tube which they would insert into the bowel to keep it open.

At this point Janet said her son simply said, “I am desperate for an orange juice, I am so thirsty”. This is a moment that still haunts her. “All Mark wanted was a drink and I could not do this for him,” she says.

Eventually, Mark was told he could have sips of clear fluid - the first liquid to pass his lips in four days.

That night, Janet went home exhausted. She had had nowhere to sleep but the plastic hospital chair for four days and needed some rest.

22:20

Mark became extremely agitated according to his father, and described the pain he was in as “the worst of his life”.

He requested that a nasogastric tube be inserted down his throat to relieve the pressure in his stomach. It was something the consultant had told him to ask for if his pain increased. Richard says his son was desperate.

But a nurse refused his request, saying the tube wasn’t appropriate.

Richard says he lost his cool at that point and said angrily: “For God’s sake can’t anybody in this hospital do their job properly, that’s not what the consultant said.”

Just before midnight

Mark phoned his mother at home. He pleaded with her to come back to the hospital, saying he was in terrible pain and the nurses were refusing to put a tube in.

Janet overheard her son tell another nurse that he needed a tube and he wanted it now. She said the nurse replied sharply: “Well you can’t have it now, you will have to wait.”

Mark was beside himself with pain. “I thought nurses were supposed to care for you and not shout at you,” his parents remember him saying.

Mark did eventually get the pressure-relieving tube, but it didn’t work. A subsequent independent report - published in 2018 - said it may have been the wrong size or become blocked.

This was the last night of Mark’s life.

His failing health should have been flagged up by the hospital’s Early Warning System (EWS), which scores patients according to key markers including heart rate and temperature, but the nurses failed to do this properly.

The independent investigation later concluded the poor calculation of the Early Warning System was a “significant missed opportunity to recognise the severity of Mark’s condition” because this would have triggered an urgent review and could have saved his life.

- Nil by mouth

- No intravenous nutrition

- Two litres of intravenous fluid

Friday

Early hours

There were some indications that this is when Mark’s bowel ruptured, which would be one explanation for his excruciating abdominal pain.

A nurse bleeped a doctor twice but nobody came.

08:00

Janet joined her husband back at their son’s bedside. She was appalled by Mark’s weakened state and obvious deterioration. She says he was very pale, tired and in excruciating pain.

A new nurse started her shift and recorded Mark as having an alarming high score on the EWS. She immediately called for help.

She contacted the Critical Care Outreach Team, who said they would see Mark, but they were called away to another patient. Mark would never be assessed by them.

Mark’s parents say a doctor asked to see his fluid charts and described him as dehydrated. They say he remarked on the fact that Mark had only been given a maintenance dose of fluid.

Mark needed a higher fluid intake than the normal maintenance dose, to make up for days of fluid loss. The doctor immediately prescribed extra fluids and the first intravenous liquid nutrition of Mark’s five day stay in hospital.

Just how much fluid he was then given has become of great significance.

Mark's last hours

Mark’s parents say staff pumped more and more fluid into him.

At one point he sat on the side of the bed in “absolute agony”. Janet says she asked him if he was struggling to breathe. Her son replied that he was, and he wondered if this would mean his operation would be brought forward.

His mother says she could hear a strange, crackling noise in his lungs when he breathed.

She rushed out to speak to a junior doctor. She claims that doctor described Mark as having mottled skin and cold hands.

It’s significant because it would indicate that Mark’s body was shutting down. The 2018 report into his death later concluded that it was unlikely that Mark’s skin was mottled.

The junior doctor told the family that the crackling sound was the fluid going into Mark’s lungs. Since Mark’s death, that doctor has said she may have been wrong about this and the report has supported this.

After months of research, however, the family believes the doctor had correctly spotted a condition called “fluid overload” and that Mark had been “drowning”.

An earlier version of the report suggested that in the final five hours of Mark’s life he was given more than seven litres of fluid, that’s more than double the dose that many medical experts would recommend in such a short space of time. But that was adjusted down to four litres in the latest version of the report.

Richard describes how his son’s face and body visibly swelled up. “They were just pumping it through and we could see Mark getting bigger,” he says.

Some of the doctors involved have defended this rapid rehydration as an attempt to save Mark’s life through what’s known as fluid resuscitation. The report concluded that Mark had needed “aggressive fluid resuscitation” and that it would have been “negligent” not to do so. It states that did not affect his outcome.

By 10:30

Mark had been seen by five doctors, but it would be at least another two hours before the true extent of his deterioration was recognised by senior staff.

12:30

A phone call came through to say Mark’s operation would be delayed by at least an hour.

13:35

Another doctor came to do pre-op checks on Mark and realised that he was “critically unwell”. He was pale, clammy and breathing quickly.

Within minutes, Mark was being wheeled towards the operating theatre.

His parents say their son lifted off the oxygen mask and asked: “Nothing terrible’s going to happen is it? I’m not going to die?”

Richard answered: “Of course you’re not going to die Mark, it’s not allowed on this ward.”

The lift was only a short distance away. His parents asked if they could go with him but they were told to take the stairs.

“He was terrified,” says Janet.

“We’d always gone in the lift with him before,” says Richard. “The lift doors were just closing and he looked at me absolutely terrified and that’s the last time I saw him alive.”

Mark was taken into a room next to the operating theatre where more fluids were rapidly put into his body. An anaesthetic was then administered.

Approximately two minutes later, Mark had a cardiac arrest.

Staff tried to resuscitate him for 45 minutes.

CPR was still being carried out when Richard and Janet entered the room. They had been desperate to be with Mark.

14:53

Mark was pronounced dead.

His parents held their son’s hand.

Janet said she just felt numb and Richard, who was very distressed, simply said: “I’m sorry Mark.”

- Nil by mouth

- Oral and intravenous glucose nutrition

- Mark’s estimated fluid intake - an initial report concluded 7.175 litres - but that was adjusted down to 4 litres in the later report

Mark's family

Janet says she and Richard have an overwhelming sense of guilt that they didn’t do more to protect Mark.

Richard has taken to sleeping downstairs in the front room of their small, two-bedroom house in Kendal. He cannot bear to go upstairs and walk past his son’s bedroom.

“He was 6ft 7in and quite heavy, and if he was moving around the house, you knew it. What I can’t stand is the permanent silence,” says Richard.

“We scattered his ashes in his favourite swimming spot at Windermere and we go there every Christmas.” From the end of the jetty, he drops a card addressed to his son into the freezing water and says, “I’m sorry Mark.”

Four years later, the pain of leaving the hospital on the day Mark died is still raw.

“I had been constantly with Mark for 22 years,” says Janet. “Leaving someone like that is terrible. Even though they are dead, you still think of them as being on their own.”

She says that she and Richard walked back to the ward alone and asked if they could see one of the nurses who had looked after Mark that morning. When they saw her, the nurse gave them a hug and was in tears.

Then they went to Mark’s room, collected his clothes and left the hospital alone, without any support.

They were in complete shock.

Mark's family

Janet says she and Richard have an overwhelming sense of guilt that they didn’t do more to protect Mark.

Richard has taken to sleeping downstairs in the front room of their small, two-bedroom house in Kendal. He cannot bear to go upstairs and walk past his son’s bedroom.

“He was 6ft 7in and quite heavy, and if he was moving around the house, you knew it. What I can’t stand is the permanent silence,” says Richard.

“We scattered his ashes in his favourite swimming spot at Windermere and we go there every Christmas.” From the end of the jetty, he drops a card addressed to his son into the freezing water and says, “I’m sorry Mark.”

Four years later, the pain of leaving the hospital on the day Mark died is still raw.

“I had been constantly with Mark for 22 years,” says Janet. “Leaving someone like that is terrible. Even though they are dead, you still think of them as being on their own.”

She says that she and Richard walked back to the ward alone and asked if they could see one of the nurses who had looked after Mark that morning. When they saw her, the nurse gave them a hug and was in tears.

Then they went to Mark’s room, collected his clothes and left the hospital alone, without any support.

They were in complete shock.

“I was promising him he’d be home for Christmas and would be swimming in the lake in the summer, and then he’s just left lying unsupervised in the room,” says Richard.

The family had been told by one of the doctors that there would need to be a post-mortem examination because Mark had been so young and his death was unexpected.

A week later, however, when Janet went back to the hospital she was told that the coroner had decided not to carry out a post-mortem and that the coroner’s decision was final.

She has since discovered that’s not correct and that families can request a post-mortem.

Janet says in the following days and weeks in the lead-up to Christmas, a time of year Mark had loved, she was numb. Richard says he became very angry - he just couldn’t believe the hospital could have let their son die.

Mark had always been with them. Because of his autism, he had relied heavily on his parents as his link to the outside world. His mother had become his voice. He would tell her what he wanted to say so that she could repeat it for him. That was why they had ensured he was never left alone at the hospital.

They have since been described as his own personal CCTV, because they witnessed Mark’s ordeal minute by minute. In the weeks following his death, they increasingly questioned what they had seen.

Eventually, they took their concerns to their family doctor, who wrote to the hospital seeking answers.

Detective work

Richard describes himself as having high-functioning autism, with a high IQ and a scrupulous attention to detail. In particular, he says he’s good at analytical work and spotting patterns.

So, as Mark’s final five days played over and over in his mind, he felt compelled to try to understand what had gone wrong at the Royal Blackburn Hospital.

The couple had requested Mark’s full patient notes and, after several months, they say the hospital sent them a bundle of loose documents in no particular order.

Some of the paperwork was unsigned and undated, with names and times missing. In fact, one of the documents didn’t relate to Mark at all - it concerned another patient.

Richard set about reviewing them, trying to piece together the medical events in the week of Mark’s death. He wanted to see if there were warning signs.

Richard learned how to read patient notes, to spot where crucial information was missing and compare Mark’s care with NHS guidelines.

Where he had concerns, he fired off requests to the hospital for more information - but he says each new piece of information prompted more questions.

“I spent three-and-a-half years virtually chained to my laptop,” Richard says.

“I think there have been times when Janet and [their other son] Alan wished I had stopped doing what I was doing,” he says. But as more question marks arose about their son’s treatment, Janet wholeheartedly supported her husband.

“His care was appalling from start to finish,” says Janet. “After he died, it carried on because they [the hospital] didn’t want to come forward and admit anything.

“We’ve had to push and push to get information out of them and that’s why we’re here in 2019 discussing something that happened in 2015 because of the pushing. [There have been] delays in responses. Our opinion is, they want this brushed under the carpet and gone away.”

The couple were to learn that the coroner had decided not to carry out a post-mortem examination after receiving the death referral certificate from the hospital - which indicated that Mark had died of a “natural cause”.

They were astonished that anyone might reach that conclusion and raised more questions. The hospital has since described this as a “slip up”.

The Royal Blackburn Hospital reported Mark’s death as a “Suspected Serious Incident” almost two months later. Hospitals are required to report such incidents within two days.

Further concerns arose when it emerged that the hospital Trust’s internal investigation did not compel the staff who treated Mark to give evidence.

Eventually, they turned to their MP, the former Liberal Democrat leader Tim Farron, for help.

He arranged for them to meet the then Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt. The Stuarts say that within minutes of explaining Mark’s ordeal, Hunt had ordered an independent report into the 22-year-old’s death.

The new investigation was carried out by a company called Verita, which had to rely heavily on information provided by the hospital. The Stuarts had a number of meetings with investigators but weren’t happy with the questions they were asking hospital staff.

“Mark’s care fell below our usual standard and immediate actions were taken”

The Verita report published in 2018 revealed a catalogue of serious failings at the Royal Blackburn Hospital, but the family say it failed to get to the bottom of who had been responsible for Mark, where they were at key moments, why other patients were prioritised ahead of him and why nobody realised how desperately ill he was until it was too late.

“Many of the key questions remain unanswered,” says Farron. “And much of what has come to light has been thanks to the painstaking and relentless detective work undertaken by the family, who have left no stone unturned in their pursuit of the truth. If ever a case paints a damning picture of systemic problems at all levels of an organisation, then this is it.”

East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust, which oversees the Royal Blackburn Hospital, has apologised unreservedly to the family for “a number of shortcomings in relation to Mark’s care”.

It has said: “It was immediately recognised and acknowledged by the Trust at that time that Mark’s care fell below our usual standard, and immediate actions were taken.”

It said the Trust had acted on the recommendations of all the investigations.

But because of the family’s ongoing concerns, NHS investigators in north west England have offered to meet the Stuarts to discuss the independent report into Mark’s case. Those investigators could address any shortcomings in the report.

Autism

While the family says many questions remain unanswered about their son’s care, what seems clear is the profound lack of understanding about Mark’s autism by hospital staff and the risks he ran as a result.

“The conduct of the nursing staff on duty overnight fell short in relation to treating people with kindness, respect and compassion”

The Verita report specifically mentions Mark’s autism as a factor leading to his death.

“Mark and his parents were disadvantaged from day one by a lack of reasonable adjustments at crucial stages of his treatment. We believe this did contribute to the final outcome,” it said.

On Mark’s final night when he was in agony and desperate for pain relief, there was a heated exchange with nurses.

“The conduct of the nursing staff on duty overnight… fell short of the standards set out in the nursing and midwifery code of practice in relation to treating people with kindness, respect and compassion.” the report concluded.

Jane Harris, Director of External Affairs at the National Autistic Society, describes the findings as “disturbing and completely unacceptable”.

“It’s a tragedy that Mark’s life was cut short. The report found no evidence that the health care professionals involved in his care considered his needs as an autistic man.”

Autistic people often need more time to understand and answer questions - or they express pain differently - she explains.

“They can be over-sensitive or under-sensitive to things like light, sound or touch, which can make already stressful situations overwhelming.

“If these reasonable adjustments aren't made their health can be at risk. It’s 10 years since the Autism Act and almost 25 years since the Disability Discrimination Act - all public services should be adapting their work for autistic people.”

Verita says it stands by its 2018 conclusions. It also says his parents were fully involved in the report investigations.

“We believe our report, which was highly critical of the NHS Trust involved and supports the majority of the family’s concerns, is thorough and fair,” says Verita’s Managing Director Ed Marsden.

“We understand how important it is that Mr and Mrs Stuart feel the tragic death of their son is properly investigated. We welcome any further scrutiny of our approach and findings.”

Although Janet and Richard welcome the offer to meet NHS investigators, they are unsure whether it will help them uncover the full facts about how Mark died. They have been waiting since August to hear when the meeting will take place.

Meanwhile, the NHS in England is beginning work to develop a new training programme for all staff who come into contact with patients with autism and learning disabilities. It will spend £1.4m on it and around 1.1 million NHS staff - working in hospitals and the community - are likely to be eligible for training.

A new national system is also being rolled out across hospital trusts to improve the way patient deaths are handled. Each trust in England will have a Medical Examiner who will check death certificates for errors and liaise with families to see if there are any concerns.

“The introduction of this strategy cannot come soon enough for this family, where patients, staff and families will all be able to submit data to the system, or log concerns about their care,” says Tim Farron.

He says that had this been in place when Mark died, his parents Janet and Richard might have been spared their fight for justice.

“If they’d told us at the beginning what had gone wrong, and they were very sorry -if they’d done a post-mortem and it had come back that he had died of something they’d caused - it would have been awful for us. But we would have accepted it a lot sooner,” says Janet.

Correction: An earlier version of this article indicated that the Department of Health and Social Care had ordered a review into the independent investigation. Instead, NHS England has said investigators will meet with the family to discuss their concerns.

Credits

Author: Sophie Hutchinson

Producer: Matthew Flintoff

Photography: George Carrick, Stuart family, Google

Graphics: Sana Jasemi

Online production: Paul Kerley

Editor: Kathryn Westcott