Jack Adcock wasn’t himself when he returned from school.

He later started vomiting and had diarrhoea, which continued through the night.

In the morning Jack was taken to the GP by his mother, Nicola, and referred directly to Leicester Royal Infirmary’s children’s assessment unit (CAU).

Nicola Adcock

Less than 12 hours later he was dead.

“Losing a child is the most horrendous thing ever. But to lose a child in the way we lost Jack – we should never have lost him,” Mrs Adcock says.

08:30

Trainee doctor Hadiza Bawa-Garba arrived at work expecting to be on the general paediatrics ward - the ward she’d been on all week.

She had only recently returned to work after having her first baby. Before her 13 months’ maternity leave, she had been working in community paediatrics, treating children with chronic illnesses and behavioural problems.

Dr Bawa-Garba

But when medical staff gathered to discuss the day’s work, they were told someone was needed to cover the CAU – the doctor supposed to be doing it was on a course. And Dr Bawa-Garba volunteered to step in.

She also carried the bleep – which alerts the doctor that a patient needs seeing urgently on the wards or in the Accident and Emergency unit, across four floors of the busy Leicester Royal Infirmary – and was required to respond to calls from midwives, other doctors or parents.

Soon after Dr Bawa-Garba took over, the bleep went off – a child down in the accident and emergency unit, several floors below, needed urgent attention and she missed the rest of the morning handover.

10:30

Back in the CAU, Dr Bawa-Garba was asked to see Jack Adcock by the nurse in charge, Sister Theresa Taylor, who was worried he had looked very sick when he had been admitted.

She was the only staff nurse that day. Because of staff shortages, two of the three CAU nurses were from an agency and not allowed to perform many nursing procedures.

“Jack was really lethargic, very sleepy. He wasn’t really very with it,” says Mrs Adcock. She told medical staff he had been up all night with diarrhoea and sickness.

The boy’s hands and feet were cold and had a blue-grey tinge. He also had a cough.

“I knew that I had to get a line in him quickly to get some bloods and also give him some fluids to rehydrate him,” says Dr Bawa-Garba. He didn’t flinch when she put his cannula in.

Because of a pre-existing heart condition, Jack had been taking enalapril – a drug to control his blood pressure and help pump blood around his body – twice a day.

But Dr Bawa-Garba says she didn’t want him to have the enalapril, because he was dehydrated and it might have made his blood pressure drop too much.

Because of this, she says, she left it off his drug chart.

She then asked for an X-ray to check Jack’s chest. Blood was taken – some was sent down to the labs, while a quicker test was done to measure his blood acidity and lactate levels – the latter being a measure of how much oxygen is reaching the tissues. The tests revealed his blood was too acidic.

“A normal pH is 7.34 – but Jack’s was seven and his lactate was also very high. A normal is about two and his was 11, so I knew then he was very unwell,” Dr Bawa-Garba says. She gave him a large boost of fluid – a bolus – to resuscitate him.

Her working diagnosis was gastroenteritis and dehydration.

But she didn’t consider that Jack might have had a more serious condition. It was a mistake she regrets to this day.

11:00

Jack had been admitted under the care of Dr Stephen O’Riordan, the consultant who was supposed to be in charge that day – but he hadn’t realised he was on call and had double-booked himself with teaching commitments in Warwick and hadn’t arrived at work.

Another consultant based elsewhere in the hospital had said she was available to help and cover him if needed – although she had her own duties.

After an hour of being on fluids to rehydrate him, Jack seemed to be responding well.

“He was a little more alert and we thought he was getting better,” Mrs Adcock says.

Dr Bawa-Garba thought that too.

One of the less experienced doctors in the unit had been unable to do Jack’s next blood tests. They had tried but couldn’t get blood, so Dr Bawa-Garba went to do it herself.

This time, when Dr Bawa-Garba went to take blood from his finger, Jack resisted, pulling away.

“That kind of response, to me, said that he was responding to the bolus,” she says. “Also, the result I got showed that the pH had gone from seven to 7.24. In my mind I’m thinking this is going the right way.”

However, not enough blood had been taken to get another lactate measurement.

12:00

Dr Bawa-Garba looked for Jack’s blood results from the lab. She had fast-tracked them an hour-and-a-half earlier. But when she went to view them on the computer system, it had gone down.

The whole hospital was affected. This meant not only that blood test results were delayed, but also that the alert system designed to flag up abnormal results on computer screens was out of action.

She asked one of the doctors in her team to chase up the results for her patients, and took on some of that doctor’s tasks.

Those tests would have indicated that Jack may have had kidney failure and that he needed antibiotics.

15:00

By this point, Jack was sitting up in the bed drinking juice.

“I automatically thought he was perking up,” says Victor, Jack’s father.

Because he had stopped vomiting, Dr Bawa-Garba prescribed some Dioralyte – rehydrating salts.

But the fluid he was losing from having diarrhoea had not been documented by his nurse.

Dr Bawa-Garba also reviewed Jack’s X-ray, which had been ready for a few hours. Dr Bawa-Garba says no-one had flagged it was available.

She says she had been busy with other patients – including a baby with sepsis that needed a lumbar puncture – and this was the first opportunity she had had to review it.

The X-ray showed that Jack had a chest infection so she prescribed antibiotics.

But Dr Bawa-Garba says she wishes she had given him antibiotics sooner.

This was the last time Dr Bawa-Garba treated Jack, who was also being cared for by an agency nurse. The nurse was doing his observations - including his temperature, heart rate and blood pressure - but did not record them regularly.

16:00

Consultant Dr Stephen O’Riordan arrived at the hospital.

“I hadn’t worked with him before, so I introduced myself,” Dr Bawa-Garba says.

She then went to chase up Jack’s blood results, which still hadn’t come through – the doctor she had assigned to do it hadn’t managed to get them.

Dr Bawa-Garba tried a number of extensions before managing to speak to someone. They read out Jack’s results and she noted them down. She says she was looking out for one particular test result called CRP, which would confirm whether Jack’s illness had been caused by bacteria or a virus.

She noted it was 97, far higher than it should have been, so she circled it. But she says she was concentrating so much on the CRP that she failed to register that his creatinine and urea were also high – signalling possible kidney failure.

16:30

During the afternoon handover, Dr Bawa-Garba told Dr O’Riordan about Jack – his diarrhoea and vomiting, heart condition, and enalapril medication. She says she told him Jack’s lactate level was 11, and mentioned some of the other blood test results. She said she had started him on antibiotics for a chest infection, and asked his advice about the fluids Jack was being given.

She says Dr O’Riordan noted down what she said and ordered repeat blood tests. Dr Bawa-Garba says she had assumed he would go to see Jack - based on the description she had given and the fact he had asked for further tests - but he didn’t.

19:00

By this time, Jack had been moved to ward 28 under the care of a different team. On his way up there, he had been sick again.

It was at this point that another failing in Jack’s care occurred.

Mrs Adcock says she asked a nurse looking after Jack on that ward if she could give him his enalapril – the medication to regulate his blood pressure. He was due his second dose of the day.

She recalls the nurse telling her she’d checked with another doctor on duty.

Mrs Adcock says she was told the nurse wouldn’t be able to give the medication to Jack, as it had not been prescribed, but his mother could. So Mrs Adcock gave it to him.

The nurse later said she had also asked for a doctor to come to see Jack.

“We’d got Toy Story on but he was still knocking his oxygen mask off,” Mrs Adcock says.

“I was just saying, ‘Come on sweetheart go to sleep,’ and I was rubbing his face. I’ll never forget – he closed his eyes and I thought something’s not quite right. His tongue, or his lips, looked blue. I ran out of the room, saying, ‘Can someone come and look at Jack?’”

20:20

Dr Bawa-Garba had been on call for more than 12 hours when an emergency call went out for a patient who had suffered a cardiac arrest on ward 28 and doctors and nurses rushed to help.

In the morning, Dr Bawa-Garba had had to intervene to stop doctors from trying to resuscitate a terminally ill boy who had a “do not resuscitate” order.

She assumed it was the same boy. What she didn’t know was that Jack had subsequently been moved to the same ward as the boy who had crashed in the morning – ward 28.

A terrible confusion was about to follow.

“While we’re running up the stairs, all I was thinking is, ‘It’s the child with the do-not-resuscitate again – that someone is trying to resuscitate. This is a mistake,’” she says.

When she reached the fourth floor, at least 11 people were already in the side room, she says.

Meanwhile, Nicola Adcock was waiting outside the room. In that moment, Dr Bawa-Garba didn’t recognise her. She says:

I walk in and say, ‘He’s not for resuscitation,’ because I thought it was the child with the ‘do not resuscitate’ order.”

Dr Bawa-Garba says she was then told by another doctor that the patient was not the same boy as earlier – but was Jack Adcock.

“I was shocked and I was like, ‘Why is Jack crashing?’” she says.

She told the team to continue the resuscitation.

“I remember going hysterical and just thinking, you know, ‘Please look after my little boy,’” says Mrs Adcock. “And then I remember somebody taking me back into the room and telling me, ‘Jack needs his mummy.’”

At 21:21 the decision was made to stop resuscitation. Jack had died of sepsis. Experts later said the interruption to the resuscitation had not contributed to his death – but he shouldn’t have been given enalapril and he should have been given antibiotics much earlier.

At the Adcocks’ home in Glen Parva, a suburb of Leicester, Jack’s sister Ruby has moved into his old room. His has been recreated in the room she vacated. Stars featuring handwritten messages from Jack’s schoolmates, saying how much they will miss him and his cheeky laugh, adorn the navy blue walls of the replica bedroom.

“It’s my way of coping,” says Mrs Adcock. She says she has yet to grieve.

The investigations, court proceedings, and appeals have taken a toll on the family.

I blame Dr Hadiza Bawa-Garba for my son’s death and I will never, ever, ever, ever forgive her.”

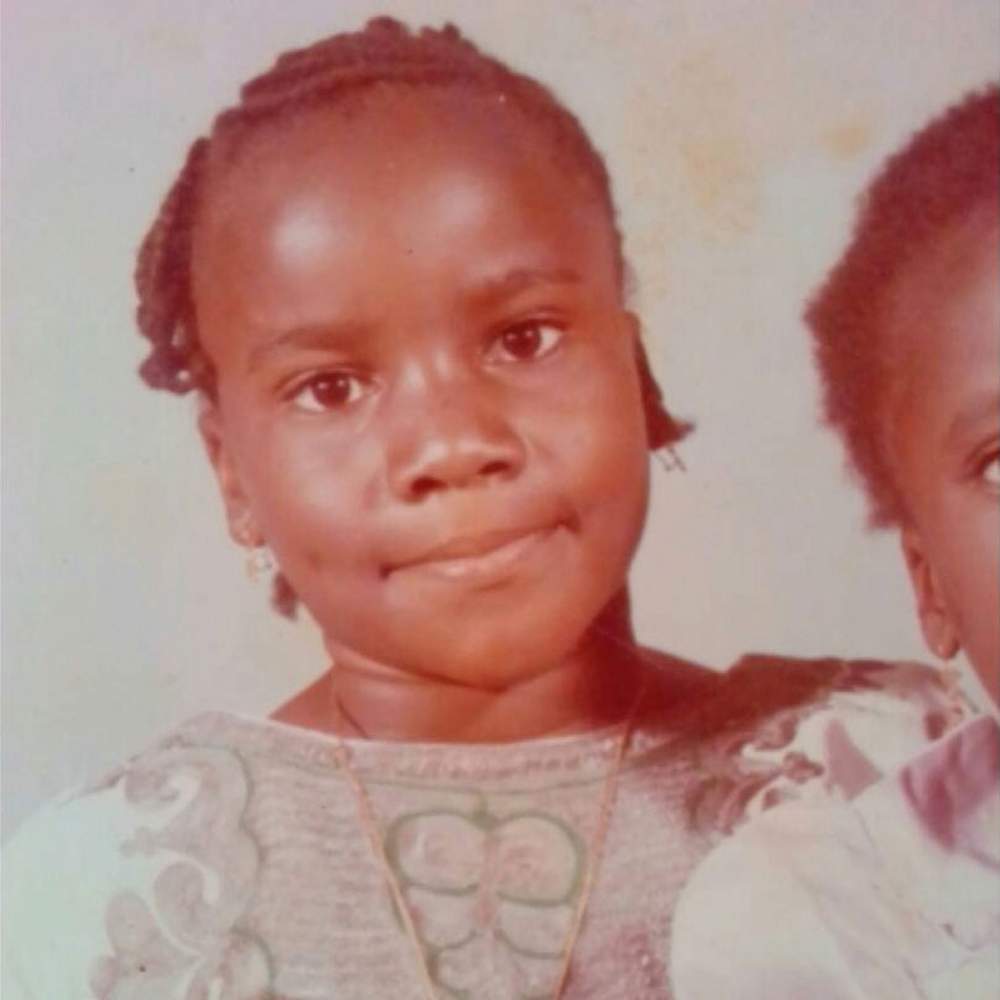

She describes Jack as a “joyful little boy” and says he and his younger sister, Ruby, adored each other.

Jack used to love dancing, swimming and going to watch Leicester City football team, says his father, even though he had been in and out of hospital during his short life.

“We were season ticket holders but since that happened [Jack’s death] I haven’t been able to go,” he says. “I can’t face it.”

Jack Adcock

The night Jack died, Mr and Mrs Adcock were taken into a room off the ward, where they were met by doctors they’d never seen before.

“We were told, ‘I’m really sorry but your son’s passed away,” says Mrs Adcock. “It just didn’t sink in.” She remembers them saying he had had pneumonia and an internal bleed.

She asked to see her son. The last time she had seen him, he had been asleep and had looked peaceful. “He had no tubes, he had nothing,” she says.

This time, “there was blood – I just couldn’t believe it was him, my baby, gone”.

Everyone on the ward was crying, she says, including Dr Bawa-Garba, who was sobbing. “Nobody expected Jack would die.”

The doctor came over to express her condolences and Mrs Adcock thanked her for looking after Jack.

“I wish I could take those words away. I never knew then what I know now,” she says.

The following day, Saturday, the family was invited back to the hospital to meet a group of doctors, nurses and managers from the trust to discuss what had happened.

Minutes taken by one of Mrs Adcock’s friends from university, whom the family had invited to the meeting, give an indication of what was discussed.

The hospital representatives apologised for the boy’s death and said they would investigate.

“They said he just wasn’t looked after; he didn’t have the right support; he wasn’t given the right care,” Mrs Adcock says. She wanted to know about the interrupted resuscitation and so they talked about that too.

The family was also told that a junior doctor had failed to recognise the severity of Jack’s condition, according to the minutes.

The police then arrived – there was to be an investigation after the unexpected death of the child.

“I remember being absolutely terrified, thinking, ‘I haven’t done anything, why are the police here?’” Mrs Adcock says.

After Jack’s post-mortem examination, two days later, the family was told that he had died of a streptococcal infection and had developed sepsis and they could make plans for his funeral.

Jack Adcock

“Everything was in place. There was an article going in the paper on the Friday to say when his funeral was going to be,” Mrs Adcock says.

But then they were asked to cancel their plans and meet the police at the coroner’s office to discuss an inquest.

“As you can imagine at that point, we felt physically sick – the anger raged. We just could not believe what we were hearing, so automatically we said, ‘So you’re telling us someone’s responsible for our son’s death?’” Mrs Adcock says.

There was then a second post-mortem examination in case criminal proceedings were opened.

“It took three months to get my little boy back, to be able to lay him to rest,” Mrs Adcock says.

Not a day goes past, Dr Bawa-Garba says, when she doesn’t think about the day Jack died.

I am sorry for not recognising sepsis and I am sorry for my role in what happened to Jack.”

The 41-year-old mother of three says the impact on her and her family has been huge.

She has had to move house and unpleasant material was posted on social media.

“I had parents from my daughter’s school asking if I was OK because they were getting leaflets in their letterboxes saying that they should sign a petition to say that I should be struck off,” she says.

The case attracted a lot of media coverage.

“I’m a very private person, but I had my face in the newspaper.”

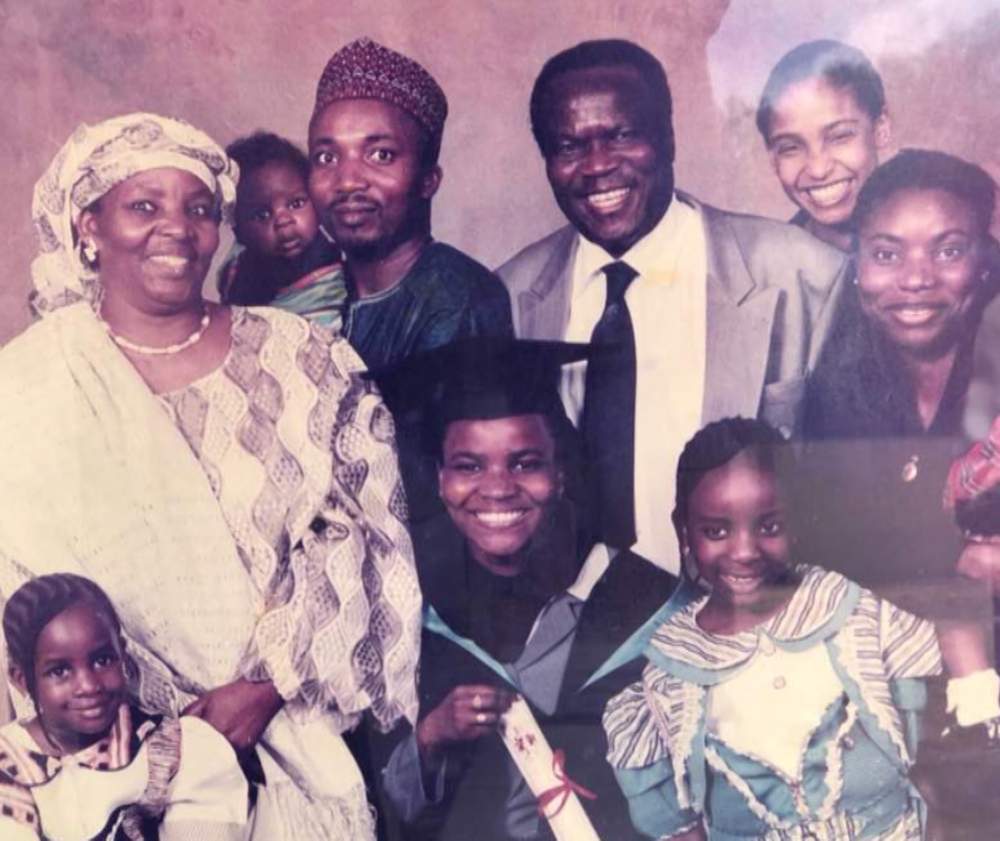

Dr Bawa-Garba had enjoyed an unblemished career before Jack’s death and was well-regarded by her colleagues.

Hadiza Bawa-Garba

Born in Nigeria, she had wanted to be a doctor since she was about 13 years old, after recovering from malaria. At 16 she moved to the UK to study for her A-levels.

After her first degree at Southampton University, she studied medicine at Leicester and set her sights on becoming a paediatrician.

Hadiza Bawa-Garba and family

“I've been in the UK for more than half my life,” she says. “I love the NHS. I love the fact that people can get access to free medical health and that you can be part of that process.”

But that all changed the day she covered for a colleague at the CAU.

“The last picture I have of Jack is him sitting up drinking from a beaker, nothing prepared me to see him crash,” she says.

“After I realised that we were actually resuscitating Jack, I just couldn’t understand why he had crashed. When the team wanted to stop, I didn’t want to stop - because in my mind I'm thinking he’s not meant to crash,” she says.

Afterwards, she went to the nurses’ station and sobbed.

“I just couldn’t control myself and I'm not usually a weepy person,” she says. “I just kept thinking, ‘How did that happen? Why did he crash? What went wrong?’”

Dr Bawa-Garba recalls the moment that Mrs Adcock came up to her to thank her for her help. “I said to her, ‘I'm really sorry about the outcome – I don't know how this happened,’” she says.

Later that night, Dr Bawa-Garba called Dr O’Riordan – the consultant who had arrived in the afternoon, after double-booking himself that day – to tell him about Jack’s death. She went home at 23:00 – some 15 hours after she had started her 12-hour shift – and updated Jack’s notes with what had happened at the resuscitation.

The following day, she was back at work at the assessment unit.

She knew the hospital was meeting the Adcocks and asked if she could attend. But she says Dr O’Riordan told her that she had to get on with her clinical duties.

The consultant then added to the notes that Dr Bawa-Garba had made.

He wrote that Dr Bawa-Garba had “not stressed” to him that Jack’s lactate level was 11.

On Sunday, struggling to process what had happened, Dr Bawa-Garba phoned Mrs Adcock to say she was sorry for the family’s loss.

“I just wanted to reach out to see how mum was holding up because it must be devastating,” she says.

The following day, she says, she was admonished by Dr O’Riordan for making that call and told not to have any more contact with the family because an investigation was to be launched.

He then told her that they needed to discuss Jack’s death properly because he thought she hadn’t highlighted to him how ill Jack was, she says. He wanted to talk about how things could have been done differently to stop it happening again, she adds.

Dr Bawa-Garba had already started to write down her reflections.

“When you have a case that has had an impact on you, you write down how you feel and what you would change,” she says. “I made my own action plan about how I would be able to address those things that I wish I had done differently.”

On 25 February, a week after Jack’s death, Dr O’Riordan asked Dr Bawa-Garba to meet him in the hospital canteen, rather than the office he shared with other consultants. She was told to list everything that she could have done differently, she says.

So she continued that personal reflective process with Dr O’Riordan in the canteen.

“I was beating myself up about every single detail and obviously wishing that I had recognised sepsis, so we spoke about that and I was very open and explained everything,” she says. “It contained what I felt I could’ve done better plus some of the things that Dr O’Riordan also felt that I could’ve done better.”

Jack died from sepsis. Sepsis is when the immune system overreacts to an infection and attacks the body’s own organs and tissues.

According to the UK Sepsis Trust, about 14,000 people die each year because it is not diagnosed or treated early enough.

At the meeting, Dr O’Riordan took notes, which he then transferred to what is called a training encounter form, she says. This contained one section for Dr O’Riordan to write on and one for Dr Bawa-Garba to document her learning points and reflections.

However, she didn’t agree with all Dr O’Riordan said and didn’t sign the form.

Both her reflections and the training encounter form were uploaded to her e-portfolio, an online system used for learning purposes.

As soon as the meeting finished, Dr Bawa-Garba says she was sent home by Dr O’Riordan.

Dr O’Riordan declined Panorama’s invitation to comment on Dr Bawa-Gaba’s account of the meeting.

Recognising her need for further training, the hospital took Dr Bawa-Gaba off the on-call rota and put her on to the paediatric intensive care unit under the supervision of a consultant.

There she would see lots of children with sepsis, some of whom would get better then get worse – like Jack, she says.

“I was probably slower than I used to be, because I was micromanaging and double-checking everything and second-guessing myself all the time,” she says.

Using what she had learned from Jack Adcock’s death, Dr Bawa-Garba says, she helped carry out a sepsis study and formed a junior doctor weekly teaching programme where doctors would discuss “near misses” or incidents when patients had died so they could learn from them.

The hospital had carried out its own investigation and Dr Bawa-Garba continued to work there.

But five months after Jack’s death, Dr O’Riordan left the Leicester Royal Infirmary and moved to Ireland.

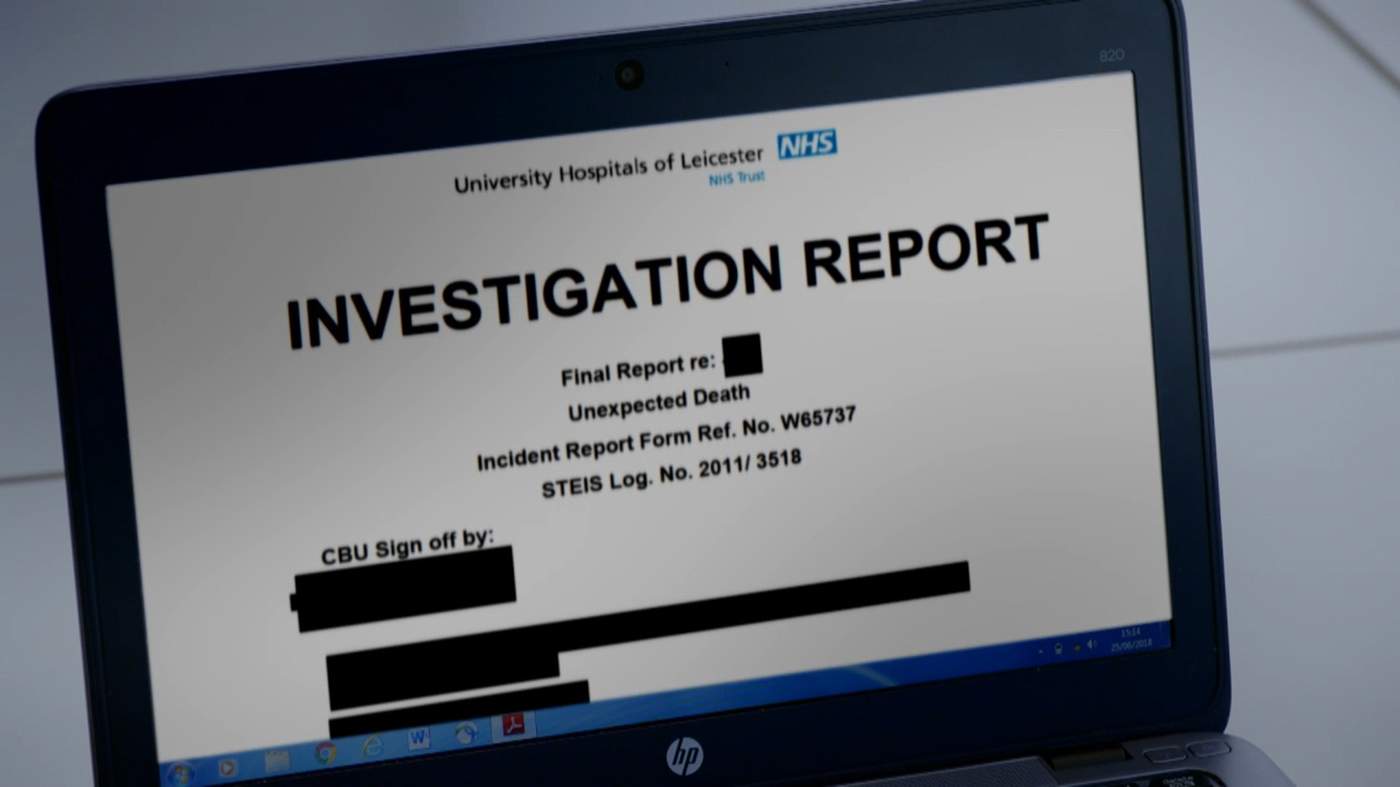

Because Jack’s death was unexpected, the hospital conducted an investigation to identify what had gone wrong with the little boy’s care. They produced a report in August 2011 and updated it six months later.

It not only pointed to errors made by Dr Bawa-Garba and nursing staff - including Dr Bawa-Garba’s failure to recognise the severity of Jack’s illness - it also found a series of “system failings”.

“I think that we let Jack Adcock down - there’s no doubt about that in my mind,” says Andrew Furlong, medical director since 2016 of University Hospitals Leicester, which includes the Leicester Royal Infirmary.

Andrew Furlong

There were six root causes for Jack’s poor care, the report said, listing 23 recommendations for improvement and 79 actions to minimise the risk of another child dying in such unacceptable circumstances.

The recommendations were wide-ranging but included:

- Robust processes for helping staff return to work after periods of protracted leave or maternity leave

- A dedicated presence of consultants on the children’s assessment unit

- New guidelines on the use of agency nurses

- Better visual prompts for staff about abnormal blood results

“Best practice shows that when you’re trying to identify learning, the way to do that is in an open culture, where people can give evidence without fear of sanction or blame,” Mr Furlong says.

Panorama has spoken to doctors who worked in the paediatric department shortly before Jack’s death. None felt able to go on the record.

They said doctors and nurses at the hospital had been raising concerns about staffing before Jack’s death.

They said consultant cover had been patchy and that factional infighting between consultants had caused problems for trainee doctors - it wasn’t something they could speak out about, they had had to keep their head down.

Junior doctors did try to raise their concerns that trainees were being used to plug rota gaps, often at the last minute. The CAU was one of the areas where there was never enough staff, and the hospital recognised that this posed a risk.

One doctor said she would pray before she went into work because she was worried something bad would happen.

In response, Mr Furlong says that as the only children’s emergency department serving 1.2 million people, the CAU was always busy.

“That isn’t unique to this trust, nor was the difficulty in recruiting doctors and nurses, too few were coming out of training nationally, a fact which the NHS locally and nationally is still struggling with. At the start of every shift, the nurses and doctors in charge routinely review staffing levels and move resources to where they are most needed,” he says.

After Jack’s death, the police started their own investigation and the Adcocks praise them for the support they have given the family.

But they say they heard very little from the hospital. They were sent a copy of the Leicester Royal Infirmary investigation and invited to discuss it, but they didn’t want to.

Dr Bawa-Garba

In February 2012 – a year after Jack’s death, and just after Dr Bawa-Garba had given birth to her second child – she received a phone call from the police. At first, she thought she had misheard what she was being told.

“The officer said, ‘We’re investigating Jack’s death as a possible manslaughter case and we need you to come down to the station,’” she says.

She went along thinking it would be a similar process to the hospital investigation. But suddenly she found herself under arrest and being read her rights. Her photograph and fingerprints were taken.

During the six-hour interview, all she could think about was her two-week-old daughter who would need breastfeeding. During phone calls home, she could hear the hungry baby crying.

The police investigation came to nothing. Seven weeks later, Dr Bawa-Garba was told that no charges were going to be brought against her.

More than a year later, in July 2013, Jack’s inquest started at Leicester Town Hall.

“We didn’t really know anything until it went to the inquest,” says Mrs Adcock. “We couldn’t speak to anyone – we weren’t really told anything.”

It was only then, the Adcocks say, they heard the “true facts” and “listened to the detail” about the errors that Dr Bawa-Garba had made.

According to Mrs Adcock, the expert witness at the inquest, Dr Gale Pearson, a paediatric intensive care consultant, stated that if Jack “had been given the right treatment, antibiotics, correct bolus, intensive care, consultant treatment, he would have not died when he died, how he died, the way he died – he may have still been here”.

“I think I collapsed, nobody could believe it,” Mrs Adcock says.

The inquest was adjourned shortly after Dr Pearson’s expert testimony and the case was referred back to the Crown Prosecution Service, which reviewed its decision to prosecute.

The family are clear about who they blame for Jack’s death – Dr Bawa-Garba and one of the nurses who had treated him. If they had done everything they could, the Adcocks say, they would have been devastated but could have said “Thank you,” and walked away. But as Mrs Adcock puts it, “All they did was contribute to my son’s death.”

Dr Bawa-Garba continued to work at Leicester Royal Infirmary, but one evening in December 2014, while she was on call on the neonatal unit, she was contacted by her educational supervisor, who asked to meet her.

Dr Jonathan Cusack

Dr Jonathan Cusack was the head of the unit, so she didn’t think much of it. But, as she sat down, he told her she had been charged with manslaughter.

“I don’t think I registered because I said, ‘Er, OK – but I need to finish my shift and I have teaching tomorrow.’ I was supposed to be teaching some medical students the next day.

He said, ‘No, you need to go home, you have been charged with manslaughter.’”

Dr Bawa-Garba passed her bleep on to another doctor and went home, her head spinning with thoughts about what would happen to her family if she were to be convicted of manslaughter and sent to prison.

As the police were investigating Jack Adcock’s death, other failings in patient care across Leicestershire were emerging.

Following the Mid Staffs scandal – where hundreds of patients were exposed to “appalling” levels of care at Stafford Hospital – a new measure to help hospitals spot problems was introduced.

The Summary Hospital-Level Mortality Indicator (SHMI) uses adjusted data from individual trusts to flag up a higher-than-expected number of deaths. It acts as an early warning system highlighting a need for further investigation.

In 2013, Leicester GPs had started to become concerned about the University Hospitals of Leicester Trust’s SHMI. It had been higher than it should have been since the SHMI was introduced in 2010.

After deliberating with the Trust, they asked Dr Ron Hsu, then a public health consultant and now associate professor at the University of Leicester, to investigate further.

He met representatives from the local Clinical Commissioning Groups, the hospital and NHS England to devise and agree a plan.

Teams of doctors and nurses were tasked with going through the records of patients who had either unexpectedly died in hospital or died within 30 days of leaving between 1 April 2012 and 31 March 2013. It didn’t look at paediatrics.

They focused on a sample that would help them identify systematic clinical issues. This is where you learn the most, Dr Hsu says.

In large rooms set aside in the hospital, the teams pored over patients' notes looking at the kind of care they were receiving and identifying things they thought had gone wrong.

The bar was set high – a team of doctors or nurses had to be unanimous before they agreed a patient had received poor care, Dr Hsu says.

When Dr Hsu came to tally the results, he did not believe what he saw. “It was shocking. Based on what I read I was expecting around 10% of patients to have received unacceptable care,” he says.

But in fact nearly a quarter of patients in the report had received “unacceptable care” – serious errors had been made that would have increased the risk of harm.

In over half, there were “significant lessons to learn” – aspects of care that could be done better.

It included issues with “do not resuscitate” orders, delayed antibiotics, failure to detect serious illness despite multiple clinical signs, unexpected deterioration, medication errors, and IT failures.

The problems ran across all health care in Leicestershire and Rutland, but the “vast majority” of lessons came from the hospital.

“The issues were obviously longstanding and the consultants and nurses working in the hospital were not necessarily surprised by what we were finding,” says Dr Geth Jenkins, a former GP in Earl Shilton and a member of the team that carried out the review.

Dr Hsu asked to meet the medical directors of the Trust.

But at a meeting between the local clinical commissioning groups, hospitals, community organisations and NHS England to discuss the findings, the discussion soon turned from how to fix the problems to how to get the message out, Dr Hsu says.

“They were concerned about their reputation,” he says.

That December he was asked to see officials from NHS England. “They were concerned about the abruptness of the presentation, they would like it softened, as it were, maybe made user-friendly,” he says.

Later that month, he says he received a list of 50 changes – mostly relating to the colour and presentation of the report and the size of the charts. Then, the following February, he received another raft of changes.

Dr Hsu says he’s been around long enough to know if reports don’t work out well for someone, people have ways of of ensuring that the report doesn’t really get anywhere.

“They were worried that people will lose faith in the health services,” he says. “We were at the time, the fifth or the sixth largest NHS trust in England and it’s a trust that whatever happens to it, you couldn’t ignore.”

Dr Jenkins says:

It was clear NHS England wanted the report to go away.”

The University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust was not the worst, neither was it the best, he adds.

“If they found these kinds of issues when the Trust’s SHMI was high but not that high, what would they find with other hospitals that had higher ones?" he asks.

Nine months after Dr Hsu submitted his report, it was posted on the Trust website. A summary version was produced for the press and the public.

The media were carefully managed, Dr Hsu says.

“It took ages for the conclusions to become public,” says Dr Orest Mulka, a former GP in Measham, and one of the reviewers.

“And when I discovered that the media, including the ���˿���, had portrayed them as relating to the care of terminally ill patients receiving palliative care, I thought this was completely untrue. Most of the patients who died were emergency admissions who were not expected to do so.”

Mr Furlong says the Trust was the first to use this review method and now others are using similar techniques to look at what can be learned from patients who have died.

The hospital appointed Dr Ian Sturgess to consider improvements in the emergency sector. But some local GPs were frustrated and thought there was a resistance to change and a reluctance to talk openly about the problems.

In October 2014 they sent a letter sent to former Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt and Simon Stevens, chief executive of NHS England, warning of “broken systems serving patients and carers in our area”.

“Every week we receive reports from our constituent GPs informing us of incidents of distressing medical and nursing care that patients are being exposed to at Leicester Royal Infirmary,” the letter said.

The GPs went on to say that in their view the hospital was “potentially on a par with Mid Staffordshire Hospital”.

It’s a description Mr Furlong rejects. Far from ignoring problems, he says, the Trust went looking for them.

“In the Mid Staffs enquiry they found that there had been hundreds of avoidable deaths, the reviewers drew no such conclusion in this review,” he says.

NHS England declined to comment to the ���˿���.

Mr Furlong says that improvements have been made and that the review has now been repeated, with results due for publication in September.

While the review cannot be extrapolated to all admissions, both Dr Mulka and Dr Jenkins see parallels in what they found with the care of Jack Adcock.

“The issues were all laid bare - poor staffing levels; communication problems and poor handovers; IT systems not working; no senior staff on duty, with juniors left to do everything," Dr Jenkins says.

"They all walked into a toxic environment that day," he adds.

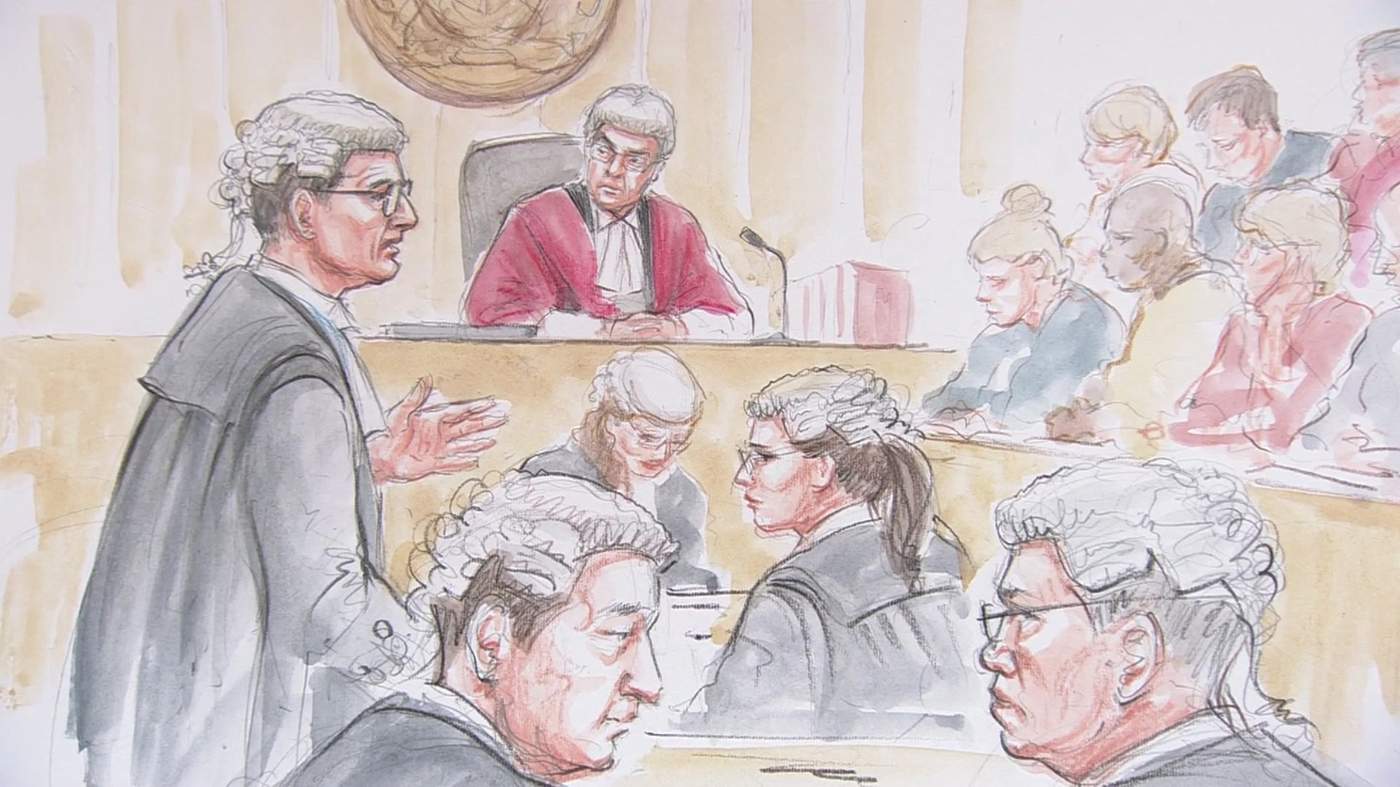

On 5 October 2015, Dr Bawa-Garba found herself in the dock in Nottingham Crown Court, along with two other defendants - nurses Theresa Taylor and Isabel Amaro.

The cells below were a constant reminder of what might happen to her.

The three pleaded not guilty to the charge of manslaughter by gross negligence at the start of what was to be a four-week trial.

“I remember sitting there and listening to their account of my actions and I felt like a criminal,” says Dr Bawa-Garba.

The case attracted a lot of media attention. Dr Bawa-Garba would travel from her home in Leicester up to Nottingham.

“I remember vividly one time we were sitting on the train and I was in The Metro paper. My picture was there and the passenger sitting opposite me kept looking at the paper and looking at me and looking up,” she says.

Dr Bawa-Garba on her way to court

Several staff from the hospital were witnesses for the prosecution and barristers representing the other defendants each cross-examined Dr Bawa-Garba.

It was the same for CAU ward sister Theresa Taylor. Isabel Amaro didn’t give evidence.

The jurors were instructed to decide whether the three defendants were guilty of unlawfully killing Jack Adcock, basing this decision exclusively on the evidence put before them.

Aspects of the trial have caused consternation among the medical profession.

“Doctors became particularly concerned when they heard about all of the systems failings at the hospital and felt these weren’t heard fully in court,” says Dr Cusack, Dr Bawa-Garba’s educational supervisor, who attended parts of the trial.

The hospital’s own investigation, which flagged up all the contributory factors and failings that had led to Jack’s death, wasn’t put before the jury, he says. Not all failings were heard, he says.

A number of other aspects of the case have also given rise to controversy.

On the fifth day of the trial, Dr Stephen O’Riordan, the consultant who was meant to be on duty the day Jack died, took the stand. As the consultant, he had ultimate responsibility for the patients admitted on the CAU that day.

Attached to his witness statement was the training encounter form containing details of his discussion with Dr Bawa-Garba in the canteen eight days after Jack’s death - the form Dr Bawa-Garba refused to sign.

Dr O’Riordan told the court that he recalled the pH was 7.08 and “the lactate was high” saying he couldn’t remember if Dr Bawa-Garba had told him the actual value at their afternoon handover, before Jack died. He said:

At no time was this patient highlighted to me as urgent, unwell, septic or that I needed to see him.”

The point of a handover, he said, was the passing of information from one junior doctor to another - the consultant’s role was supervisory to ensure the information was transferred.

Some doctors, however, contest this saying that the handover is to provide an opportunity for consultants to decide how best to manage patients, and to pick up on points that trainees have failed to flag.

“Doctors work in teams and the consultant is in charge of that team. While doctors are responsible for their actions, many feel Dr Bawa-Garba was let down by the consultant on call both on the day that Jack died and subsequently,” Dr Cusack says.

The role of the enalapril, the drug given to regulate Jack Adcock’s blood pressure, has also generated debate. Some doctors have expressed concern that its role in Jack’s cardiac arrest has been underplayed. Mrs Adcock says she feels that these doctors are blaming her for her son’s death.

At the coroner’s inquest in August 2014, Dr O’Riordan’s barrister suggested that enalapril had been a significant factor.

But the coroner, Mrs Catherine Mason, dismissed this idea.

“I have no evidence of that at all,” she said. There was nothing in the report by Dr David O’Neill, the pathologist, or from toxicology, that suggested it played a role, she said. She then repeated the point, saying that there was “no evidence that the enalapril was incorrect or caused or contributed to his death”.

Measurements of the levels of enalapril in Jack’s blood were not taken as they were thought not to be useful.

At the criminal trial, experts agreed that Jack shouldn’t have been given the drug in the condition he was in, though all accepted that Mrs Adcock had behaved perfectly responsibly by giving it to him.

They didn’t agree on how much it had affected him, though.

Dr O’Neill said whether or not enalapril played a role was beyond his expertise. But when asked if it was a “significant factor” in Jack’s rapid deterioration, he said this was “consistent with the clinical history”. His post-mortem results could not confirm or refute it.

The jury also heard from Dr Simon Nadel, a paediatric intensive care consultant in London, who thought enalapril had aggravated Jack Adcock’s condition, but wasn’t the cause of death. Another prosecution expert agreed.

Dr Nadel said the little boy was “well on down the slippery slope by then” and had a “barn door” case of sepsis. This was the most important cause of his death, he said.

Dr Bawa-Garba’s defence expert, however, thought the signs of sepsis were “more subtle”.

After two weeks, it was Dr Bawa-Garba’s turn to give evidence.

Mr Andrew Thomas QC, for the prosecution, told Dr Bawa-Garba that no-one was suggesting that she deliberately set out to harm Jack Adcock. What was at stake was whether she fell below the standard of a reasonably competent junior doctor.

He pressed Dr Bawa-Garba on the reflection she did after Jack’s death.

“List for us, please, all of the mistakes,” Mr Thomas said.

“After this case happened, I reflected on my practice and this can be found in my e-portfolio, and I listed deficiencies that I felt were in the care that I provided on that day,” Dr Bawa-Garba replied. One of them, she said, was her failure to register warning signs in the blood tests.

Mr Thomas told her to pause as people were going to write the list down. He then pressed her further and one by one, she listed how she felt she should have done better.

“I wish that I had been clearer in my communication with the consultant,” she said

“That's two. Keep going,” Mr Thomas said.

“When I reassessed Jack, I was falsely reassured because he was alert, drinking from a beaker, responding to voice, pushing his mask away because he didn't want it on his face,” she replied. She added: “I should not have relied on the nurses to get back to me with the clinical deterioration as I normally do.” She should have looked at the nursing chart, she said.

“That’s three. Number four?”

“I underestimated the severity of his illness,” Dr Bawa-Garba said.

“Number five?”

“On the reflection I did following this incident, those were the points that I looked at,” she said.

The next day was spent exploring all the points in detail. Dr Bawa-Garba continued to describe where she should have done better.

Dr Cusack says the use of her reflections made by the prosecution has made doctors fearful about admitting their errors. “All doctors are expect to regularly reflect honestly and openly on their practice to improve patient care,” he says.

At the end of the trial, the judge summed up the case to the jury. The prosecution relied on the fact she ignored “obvious clinical findings and symptoms”; did not review Jack’s X-ray and give antibiotics early enough; failed to obtain the morning blood test results early enough and act on the abnormalities they showed; and failed to make proper clinical notes.

The judge told the jury they could only convict the health professionals in front of them if they were negligent and that their negligence significantly contributed to Jack’s death or its timing. The negligence had to be gross or severe, he said - what they did or didn’t do had to be truly, exceptionally bad.

He said they should set aside any criticisms or feelings towards others involved in Jack’s care. They had to consider the circumstances within which the defendants were working when considering if they were guilty.

Dr Bawa-Garba in police custody

On 4 November 2015, the jury found Dr Bawa-Garba guilty. She was led away in handcuffs to a cell while her team worked out her bail conditions.

“I sat in that small room and prayed,” she says.

Then she asked for a pen to write. After initially being denied one, in case she harmed herself, she was given a pen outside the cell.

“I remember writing and writing until the ink ran out in the pen,” she says. “I had two very young children - my oldest is severely autistic and goes to a special needs school. So I made plans that if I was to go to prison he would have to go out and live with my mother in Nigeria.”

Nicola and Victor Adcock outside court

For the Adcocks it was the day they had been waiting for. “For a split second you think, ‘Yes, we’ve got justice for our son’s death,’” says Mrs Adcock.

Dr Bawa-Garba spent the next six weeks trying to plan for every scenario. She returned to court in December for sentencing. She had brought a rucksack with her in case she was sent to prison.

“I remember on the morning of the sentencing telling my parents that I didn’t want them there in the court in Nottingham,” she says.

I didn’t want my dad to see me being taken away in handcuffs. But he just started sobbing on that morning because I wouldn’t let him come to court with me.”

Dr Bawa-Garba was given a two-year suspended sentence. Nurse Isabel Amaro received the same sentence. Ward sister Theresa Taylor had been found not guilty.

Dr Bawa Garba applied for leave to appeal against her conviction, but this was denied in November 2016.

At the heart of this story is the tragic death of a much-loved little boy and the loss felt by the family. But there’s been a much wider impact too.

In 2017, the General Medical Council’s tribunal service suspended Dr Bawa-Garba for a year. They said that while her actions fell “far below the standards expected of a competent doctor”, they had taken into account other factors.

These included that fact she had learnt from her errors; had an unblemished record before and after Jack Adcock’s death; and the system failures at the Leicester Royal Infirmary.

The tribunal’s decision angered Mrs Adcock.

“How can somebody make that many mistakes, be found guilty by a jury and be able to practise again? It doesn’t give the public any faith in the NHS,” she says.

If you walked into a hospital and saw that doctor, would you be happy for her to treat your child?”

So Mrs Adcock approached the GMC to see if she could appeal. She set up an online petition, with thousands of people pledging support.

Charlie Massey, chief executive of the GMC, says that after receiving legal advice the GMC applied to the High Court to overturn the decision made by its own tribunal.

He denies being influenced by the Adcocks’ petition, and says the GMC acted out of the need to protect public confidence in the profession, given the seriousness of the conviction.

Charlie Massey

Dr Bawa-Garba was struck off in January 2018, meaning that she could no longer practise medicine in the UK.

“The best way to protect patients is by supporting doctors. But we are also a regulator, and sometimes we have to make tough and unpopular decisions,” Charlie Massey says.

The decision has certainly been unpopular among the medical profession. Dr Bawa-Garba’s striking off caused outrage, and led to allegations that she had become a scapegoat for a failing and unsafe NHS.

A social media storm ensued, accompanied by the hashtag “#IamHadiza”, with doctors wearing T-shirts and badges in her support.

One said:

An overworked and under-supported doctor was thrown under the bus by the GMC.”

“Drs working flat out in a broken and unsafe system,” said another.

“Huge solidarity with this doctor who could be any one of us NHS doctors working in an overstretched, purposefully underfunded and dangerously understaffed service,” added another.

For Dr Hsu, the outcry from around the country suggested that what he had seen at Leicester was widespread across the NHS.

A crowdfunding campaign also got under way to enable Dr Bawa-Garba get another legal opinion. It raised over £360,000 in about a month with contributions from around 180 countries.

Dr Chris Day, a junior doctor and one of the people behind the crowdfunding, says he was overwhelmed by the response.

“I think people want to know how it was possible that a junior doctor could get convicted for gross negligence manslaughter, going about her duties as a junior doctor - and when there were so many systemic factors at play,” he says.

Dr Chris Day

After Dr Bawa-Garba was struck off, The British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin, an organisation that aims to promote diversity and equality, has expressed concerns that healthcare workers from BAME groups are disproportionately referred to their respective regulators. They have written to the GMC.

Indeed, one official review concluded that BAME groups are also disproportionately prosecuted for gross negligence manslaughter - although it only looked at a small number of cases.

The GMC’s Charlie Massey says he understands these concerns. He says that nearly twice as many black and minority ethnic doctors are referred to the GMC by their employer than white doctors.

“And that's important, because the vast majority of referrals that come to us from employers, do result in investigations, whereas it’s a minority of complaints that are made to us by the public,” he says. A review is underway to look at the disproportionate referral rate.

Others in the medical profession have found different ways of registering a protest.

One group of doctors tore up their GMC registration certificates in front of its headquarters in London and others took themselves off the register completely.

Doctors protesting in Scotland with the politician, Anas Sarwar

Dr Peter Wilmshurst, a Midlands-based cardiologist, wrote to the GMC to ask them to investigate him. All doctors make mistakes and that is understandably scary for patients, he says.

“I’ve made clinical mistakes including delayed diagnosis and errors in treatment. Some sick patients died. I suspect that many would have died anyway but in some cases my errors are likely to have contributed to poor outcomes and some patient deaths,” he says.

“I therefore feel obliged to ask the GMC to investigate my clinical practice over the last 40 years to see whether I should be struck off the medical register.”

But Mrs Adcock says the doctors are mistaken in their interpretation of what happened. “The reason the doctors are doing what they’re doing, they’re scared for themselves. I understand that because they’re thinking if we make an honest mistake we’re going to be charged. That isn’t the case. They need to look at the number of errors that doctor made on the day for the judge to say ‘truly exceptionally bad’,” she says.

The Adcocks

In 2013, Professor Don Berwick MD, president of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in the US, was asked by the then prime minister, David Cameron, to advise about how to improve patient safety in the NHS following the Mid Staffs scandal. His report made a raft of recommendations including moving away from blaming an individual to looking to learn from errors.

“We said if there’s fear in the system people are frightened about identifying hazards, about speaking up when they make a mistake about speaking up when something goes wrong then how could it ever get safer?” he says.

Dr Don Berwick

“You could fire everybody, punish everybody and put in an entirely new workforce, you will have the same injuries and the same errors occur again unless you’ve actually changed the systems of work,” he adds.

He says that when there’s been a serious tragedy families are understandably angry.

“We have to help them understand what happened, to be open about what happened, to apologise for what happened,” he says.

But he says he has sympathy for Dr Bawa-Garba.

“Even though she made mistakes she was trapped - she was trapped in a set of circumstances which set her up for failure.”

Dr Bawa-Garba

Dr Bawa-Garba has been on a long journey. The story began in an overstretched hospital in February 2011 when she was 34. She was charged with manslaughter in December 2014 and convicted in November the following year. She was struck off the medical register in January this year. And on Monday she was reinstated to the medical register by the Court of Appeal.

The judges ruled that Dr Bawa-Garba's actions had been neither deliberate or reckless and she should not have been struck off.

The GMC has accepted the judgement.

“The lessons that I’ve learnt will live with me forever. I welcome the verdict because for me that’s an opportunity to do something that I’ve dedicated my life to doing, which is medicine. But I wanted to pay tribute and remember Jack Adcock, a wonderful little boy who started this story,” Dr Bawa-Garba said.

“My hope is that lessons learnt from this case will translate into better working conditions for junior doctors, better recognition of sepsis, and factors in place that will improve patient safety.”