Textiles and the Industrial Revolution

Before the Industrial Revolution, making textiles was a slow process carried out by people using simple equipment, mostly in their own homes.

By the end of the Industrial Revolution, the production of cloth and fabric was a huge industry based in factories, and the UK dominated the textile trade across the world.

What caused this transformation? And how did it change people's lives?

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYHow were textiles made before the industrial revolution?

The Industrial Revolution was a period of history that saw huge technological and social changes in Britain.

The arrival of complex machines and the development of power sources like water wheels and steam engines, led to the growth of factories and industry

Before the Industrial Revolution, most of the textiles made in Britain would have been made by people in their own homes.

What was the domestic system?

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYUnder this system, local textile manufacturers would have deals with individual families.

The manufacturers would provide them with raw materials, such as wool, and the families would produce finished textiles.

The families would use a spinning wheel to spin strands of wool or flax (used to make linen) into fine threads. They then used that thread on a hand-powered loom to weave it into cloth.

The manufacturer would then collect and pay for the textiles and send them to local markets.

This was known as the domestic system.

The arrival of the textile factories in the mid to late 1700s largely ended this system.

The use of large, automated machines meant that cloth could be mass produced at a cheaper cost than the cloth produced under the domestic system.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYNew inventions in the industrial revolution

In the decades before the Industrial Revolution, Britain imported huge amounts of cloth and textiles from India.

By the time the Industrial Revolution was in full flow, Britain could not only compete with the Indian imports, it produced such huge amounts of cloth and fabric that it became a major exporter of them to the rest of the world.

Several inventions made a significant difference in texture manufacturing in Britain. Here are some of the most important ones.

Flying shuttle, 1733

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe flying shuttle was the first invention to make weaving much quicker. Invented by John Kay in 1733, the flying shuttle had wheels and ran quickly along a track between the threads.

Instead of a weaver having to push the shuttle by hand, paddles at either side of the loom were operated by pulling a string. These would fire the shuttle back and forth. This allowed individual weavers to produce cloth much more quickly.

Image source, ALAMY

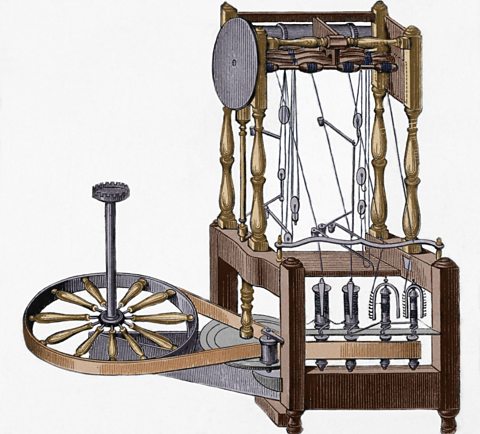

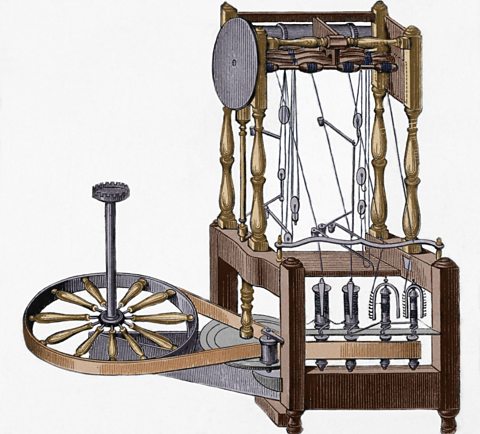

Image source, ALAMYSpinning jenny, 1764

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYOne of the earlies examples of machinery that was used to boost the production of the yarns and threads used to make cloth was the spinning jenny.

The spinning jenny was invented in 1764 by a Lancashire weaver called James Hargreaves.

Before the invention, all machines for making thread could only spin one thread at a time. This meant that created threads for cloth took a lot of time.

Hargreaves designed and built a machine that was capable of spinning several threads at the same time.

This could produce a lot of thread in a short space of time, which meant there was less need for people to carry out this work.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYWater frame, 1769

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYIn 1769, Richard Arkwright created the water frame. This was another spinning machine but it used a source of flowing water, such as a stream or river, to power it.

As a result large factories were built near sources of water, such as Stanley Mills in Perthshire.

Arkwright’s water frame could spin almost 100 threads at the same time and operate far faster and for far longer than human-powered spinning frames.

These mills could work 24 hours a day with workers at the machines for 12 hours a day.

Image source, ALAMY

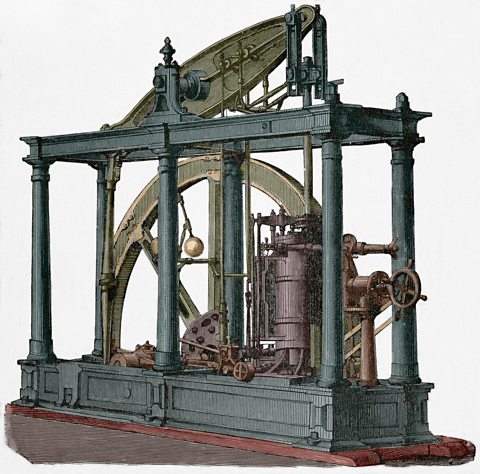

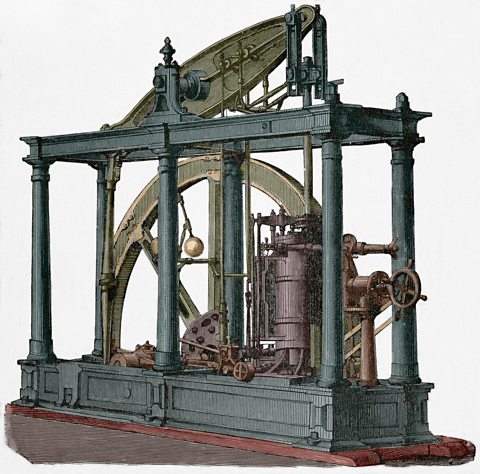

Image source, ALAMYWatt's steam engine, 1776

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe steam engine designed by Scottish engineer, James Watt, had a huge impact on the Industrial Revolution.

Before Watt’s engine, large spinning looms, like Arkwright’s water frame were powered by energy generated by giant wheels turned by water.

This meant that factories need to be built near water with a flow powerful enough to drive a water wheel.

The steam engine’s impact on the textile industry was that it freed factories from having to be located next to a source of running water.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYSpinning mule, 1779

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYIt was another Lancashire inventor who took the next major step in mechanising the manufacture of textiles.

In 1779, Samuel Crompton developed a yarn spinning machine that would borrow element from and improve on other machines such as the spinning jenny and the water frame. It became known as the spinning mule.

Like the spinning jenny, it had multiple spindles for making threads and, like the water frame, it was powered by water rather by human strength.

The spinning mules were huge – over forty metres long and using over a thousand spindles.

Crompton’s spinning mules could produce huge amounts of thread and they were in use in British textile factories for well over a hundred years.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYPower loom, 1785

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYEdmund Cartwright was destined for a career as a clergyman in the Church of England in Leicestershire until he visited one of the mills owned by Richard Arkwright, the inventor of the water frame.

Inspired by the visit, Cartwright decided to design his own machine and go into the textile industry.

Since machines for spinning thread already existed, Cartwright tried something else.

The machine Cartwright developed was the power loom. This machine helped to mechanise the process of weaving cloth using pre-spun thread.

While this early power loom did not make Cartwright rich, future developments and improvements to the power loom by other inventors helped the machine to revolutionise the manufacture of cloth.

Machines such as the power loom could do the equivalent work of lots weavers far quicker and at a much lower price.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYImpacts of textile machinery in the Industrial Revolution

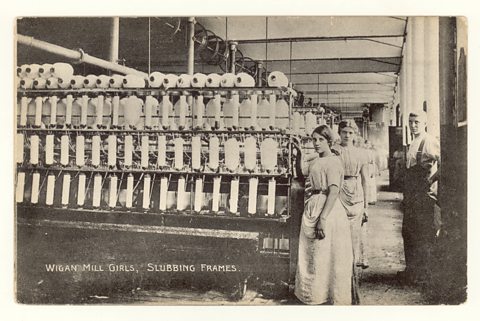

The arrival of machinery ended the domestic system and saw the manufacture of textiles move from the home to the factory.

No longer were textile workers skilled craftspeople, but unskilled workers employed only to look after the looms and machines.

Travel was difficult and so workers had to live near the factories where they worked. This meant that many people from the countryside travelled to towns and cities to live and work.

Working conditions in factories and mills

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe factories and mills employed tens of thousands of men, women, and children, some as young as four years old.

The hours of work were long – 12 hours shifts were common. Often the machines were operated night and day.

Factories were noisy, often poorly-lit and poorly-ventilated. Dust and damp caused breathing problems, noise led to hearing issues and deafness, and repetitive work, sometimes in cramped conditions, caused aches, pains and mobility problems.

There was no childcare in the industrial era, so children went to work with their mothers and were given jobs such as crawling between the looms to clear cotton waste.

This was a dangerous job that could result in a lost limb or life.

The overseer would hand out harsh punishments, such as beatings, for any child falling asleep on the job or any worker not working fast enough.

With only Sundays off, life in the factories and mills was severe.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe change to cotton

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYBefore the Industrial Revolution, the main textiles were made from wool and a plant fibre called flax. These proved difficult for factory machines to work with. Cotton was easier to work with machines and needed less preparation than wool or flax.

Cotton could also be produced more cheaply on plantations in the Americas. The cotton was imported into Britain, turned into textiles in British factories, and then sold all over the world for considerable profit.

This change from wool and flax to cotton had some serious impacts.

The cotton from the American plantations was grown and harvested by enslaved Africans. The conditions that they lived and worked in were terrible, and the cotton manufacturing was directly linked to the slave trade.

Image source, ALAMY

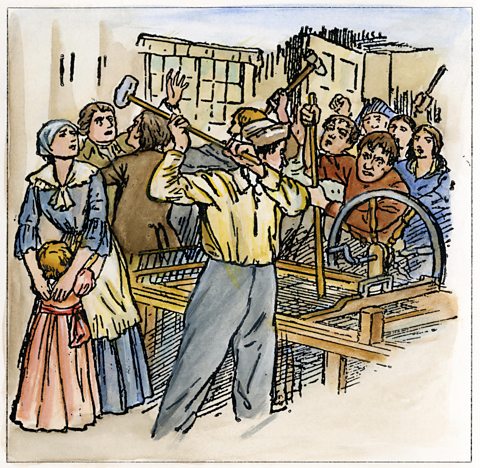

Image source, ALAMYWho were the Luddites?

Find out how new textile-manufacturing machinery threatened a centuries-old way of life during the Industrial Revolution.

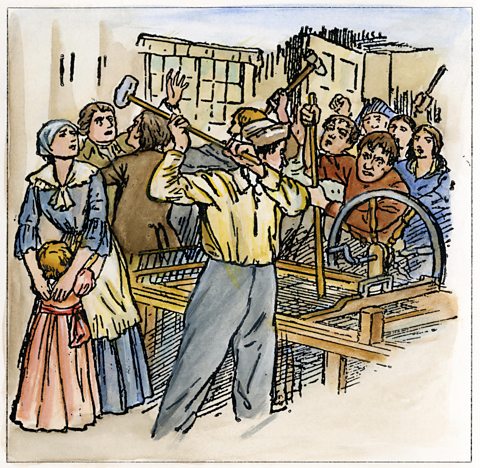

1812, a seething secret society meet late at night at the Shears Inn in Liversedge, Yorkshire, to hatch a destructive plan. They call themselves the Luddites.

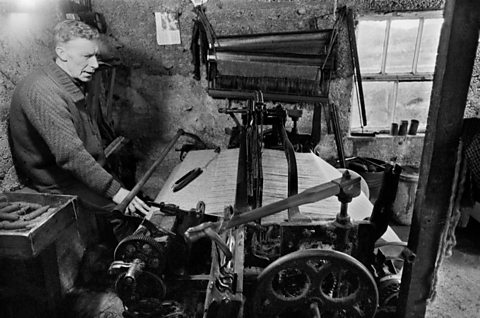

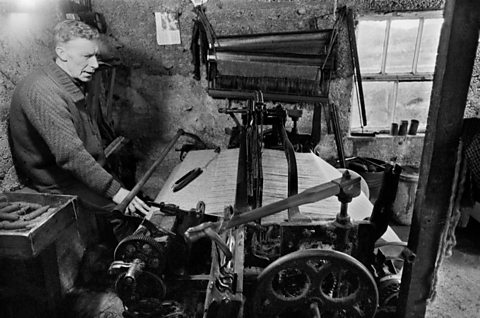

They are textile workers; men and women who earn a living making cloth the old fashioned way – at home on small weaving frames. Their way of life is under threat. The new, large machines in factories are taking all of their business. The Luddites are angry, and they intend to do something about it.

On the 12th April, 150 men descend on Cartwright’s Mill. They forced their way in and attack the textile machines with hammers and axes, smashing them to bits. Sadly for them, their protest does not end well.

Two men are shot, and many more are arrested. Even worse, the breaking of textile machines is an offence punishable by death. And seventeen of the Luddites from the Cartwright Mill attack are hanged at York castle.

In the battle between men and machines, the machines won.

For centuries leading up to this, textiles and cloth were made in people’s homes. Raw materials, such as wool, flax and cotton, would be spun into yarn using a spinning wheel and woven into lengths of fabric on a hand loom – all done by hand.

Once finished, weavers would be paid by textile merchants for the fabric they had worked so long and hard to make. This was called the domestic system, and this was the system that the machine destroyed.

Inventions such as the Spinning Jenny could spin over a hundred threads at once – far more than a worker at home.

Then came the water frame, powered by water flowing from rivers, it could run 24 hours a day with no need to rest of sleep.

All of this was bad news for home workers, and to make matters worse, anyone could work these machines. The old-fashioned home workers had been trained from a young age by their parents to spin and weave – they were really rather highly skilled. But these new machines could even be operated by children. As this handbill puts it, ‘your little children, by the help of machinery, can earn their own livelihood, and it is easy to rear a family!’

The home weavers simply couldn’t compete. The machines created tonnes of textiles far quicker and far cheaper than they ever could. And that was why the Luddites risked their lives to smash the machines; without work, they couldn’t afford to feed their families.

It was a brave protest, but it was all in vain. The machines turned small textile town like Paisley and Dundee into global powerhouses of textile production. Thanks to the power of the British Empire, cloth made in British textile mills were being sold all over the world at low prices which industries in India and other countries simply couldn’t compete with. British factory owners were getting rich.

And the British weavers? Given the choice of going hungry or going to work in the factories for less money and in bad conditions, many, reluctantly, chose the factories – working on the machines that they’d tried to destroy.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe harsh living and working conditions of the textile workers was not endured without protest.

In the early decades of the 1800s, a secret organisation of angry textile workers in the north of England formed to fight back against the factories and mill owners.

They became known as the Luddites – named after a man a man called Ned Ludd who was alleged to smashed two knitting machines in a protest in 1779.

The Luddites were textile workers who did not work in the new, large factories and mills.

The factories could produce large amounts of cloth faster and at a cheaper cost than smaller weaving workshops or individual, home-based workers.

As such, the Luddites believed that the factories were forcing down wages and making it impossible for them to earn a living.

In protest, the Luddites broke into factories and smashed the machinery used to make fabrics.

The manufacture and export of textiles was a huge business and important to the British economy. The spread of such protests to major centres of production such as Paisley and Dundee could jeopardise trade.

Luddite protests were seen as such a threat, that the government passed the Frame-Breaking Act, 1812.

The act made the destruction of textile machinery a capital offence – meaning that it carried the penalty of death.

During this period, around 60 people were hanged for their Luddite activities with lots more sent abroad to prison colonies, such as those in New South Wales, Australia.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYSecure employment

Some effects of the Industrial Revolution could be seen as positive.

Before the Industrial Revolution, employment was tied to the seasons.

Workers usually lived in rural areas and primarily worked in agriculture. Working on textiles was often secondary work to provide another income.

Agriculture work was not always secure employment. If harvests failed, workers would not be paid to pick the crops.

The textile factories offered employment all year round. The factories also employed women as well as men.

The factories also employed women as well as men, giving women the opportunity to earn their own wages and support themselves and their families financially.

While conditions in most mills were very difficult, some mill owners built accommodation for their workers and some provided facilities such as access to basic healthcare.

New ways of working and living

The poor wages, working conditions and living standards of textile workers prompted some mill owners to try to improve the lives of their workers.

One such example of this was the factory and village at New Lanark on the banks of the River Clyde in Lanarkshire.

New Lanark

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe mill was first built in 1786 by the Scottish industrialist, David Dale, and the Lancashire inventor, Richard Arkwright.

In 1799, the mill was bought by Dale’s son-in-law, Robert Owen.

Owen had worked in the textile industry since he was young and he became the mill's manager. He was also a keen social reformer who had his own ideas on how to improve the lives of the textile workers who worked for him.

Owen set about making a series of reforms at the mill:

- He improved the housing that his workers lived in.

- He built schools for young children.

- He limited the hours that people worked.

- He ended the physical punishment of workers for poor performance.

By 1860, New Lanark was Scotland's largest cotton-making mill, with over 2,500 men, women, and children working there.

Its progressive approach to improving the lives of the people who lived and worked there attracted attention from all over Europe.

New Lanark even inspired the UK Parliament to make some of Robert Owen's reforms law through acts such as the Factory Act of 1819.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYTest your knowledge

More on Industrial Revolution

Find out more by working through a topic