Durer's Rhinoceros

This week Neil MacGregor is describing empires around the world 600 years ago. Today he tells the story of the fledgling empire of Portugal through Durer's famous image of a rhino.

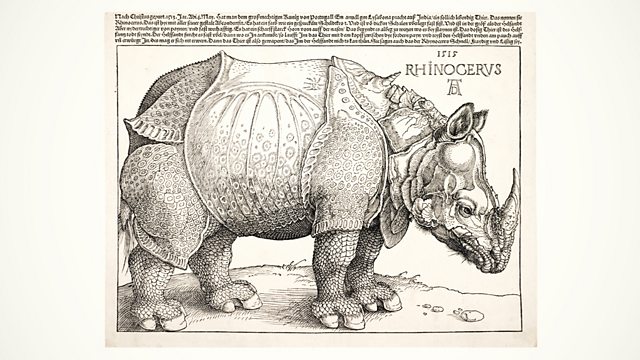

Neil MacGregor's world history as told through things that time has left behind. This week he is exploring vigorous empires that flourished across the world 600 years ago - visiting the Inca in South America, Ming Dynasty China, and the Timurids in their capital at Samarkand and the Ottomans in Constantinople. Today he examines the fledgling empire of Portugal and describes what the European world was looking like at this time. His chosen object is one of the most enduring in art history, and one of the most duplicated - Albrecht Durer's famous print of an Indian rhino, an animal he never had never seen. The rhino was brought to Portugal in 1514 and Neil uses this classic image to examine European ambitions. Mark Pilgrim of Chester Zoo considers what it must have been like to transport such a beast and the historian Felipe Fernandez-Armesto describes the potency of the image for Europeans of the age.

Producer: Anthony Denselow

Last on

More episodes

Next

You are at the last episode

![]()

Discover more programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects about art.

About this object

Location: Germany

Culture: European

Period: AD 1515

Material: Paper

��

This print of a rhinoceros was created by Albrecht Dürer, the most famous artist of his day. Dürer's celebrity was in part due to his ability to make his work both available and affordable to a mass audience. The new technology of woodcut printing allowed drawings to be mass produced; around 4000 to 5000 copies of the rhino print were probably sold in Dürer's lifetime. Dürer, however, never actually saw a live rhino and based his drawing on a brief sketch and a letter.

Which rhino inspired Dürer's print?

The rhino that inspired Dürer's print was given by an Indian sultan to King Manuel of Portugal in 1515. At the time Portugal's navy dominated the Indian Ocean and controlled the world's spice trade. The rhino was the first to arrive in Europe since the days of the Roman Empire and caused a sensation. Seeking approval for his Eastern empire, the Portuguese king sent the rhino as a gift to the pope. However, the ship carrying the rhino sank in a storm and the unfortunate rhino was drowned.

Did you know?

- The Indian rhinoceros is the world's fourth largest land animal, but can run up to 34 miles per hour.

Quite a journey

By Mark Pilgrim, Director of Conservation and Education, Chester Zoo

��

Clearly, it’s a big animal. A big male can easily weigh a couple of tonnes. They can be surprisingly fast, they’re very intelligent. But also they’re very docile in terms of they tame very quickly. So greater one-horned rhinos tend to be very laid-back, very calm in their personalities, and therefore can be moved around fairly easily. Compared to the Black Rhino which is much more highly strung, these animals are much calmer.

Of course, today we have all the bureaucratic issues; huge amounts of paperwork and veterinary certificates and all that bureaucracy that goes on with moving animals and transporting animals around, particularly exotics. But also of course these days they fly, so it’s a very quick transport, but keepers will travel with them to keep them calm. Sometimes we give them some little sedative just to keep them calm although usually we don’t need it, they’ll feed throughout the journey, and actually they travel pretty well generally.

We tend to find that while an animal’s moving, be it in a vehicle or an aeroplane, they stay pretty calm and they just eat while they’re travelling and the time they can get a little bit upset is if things actually come to a stop. But loading them on to the crate and loading them off the crate is challenging, and that’s done through long-term care and training; we train them to walk on to the crate for food, and walk off again. So it’s not that complicated if you put enough preparation time into it.

Transporting a rhino, presumably from India, to Portugal in the 1500s would have been a very different matter. I guess on the positive they didn’t have all of the paperwork to worry about in those days! But of course logistically it was an enormous challenge.

You can assume that actually their animal husbandry skills were good, they were probably extremely good people with horses, and the care that they would take transporting horses around would have been very useful in terms of transporting a rhino. But something of the size of the greater one-horned rhino, and the strength of a one horned rhino, on a sailing ship is clearly an amazing challenge.

Presumably this was a pretty calm animal, they carried huge amounts of hay and food aboard the ship, I really have no idea how long it would have taken but weeks and weeks I would imagine, probably over quite rough seas, and yes - it’s an incredible voyage.

It must have been quite a journey both for the animal and the people who were caring for it.

The richest arena of trade

By Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, historian and author

��

The arrival of the rhinoceros says a lot about the transmission of culture across the oceans, because it is true that the Portuguese were, as the historical tradition has it, pioneers in this business.

The Indian Ocean was the place to be, but to get there in antiquity and the middle ages you had this terribly laborious journey. I mean typically you had to get across Turkey or Arabia to get to the Persian Gulf. And that was terribly difficult in Christian Europe because of the hostility of the Islamic Empires that prevailed along the way. Or else you had to sail across the Nile and take a camel caravan across the Eastern Nubian Desert. Again, a ship on the red sea which was a very dangerous sea: it’s got these adverse currents and terrible rocks and things.

Eventually, you know, you get to the Indian Ocean. And when you got there you were in despair, you know, because you had nothing to sell! These guys round the Indian Ocean were so rich that they actually had everything they wanted in internal trading system and the Europeans had nothing to offer them, it was very difficult to break in.

When the Portuguese got in there via the Atlantic and found their way around the Cape of Good Hope they had ships with them which obviously, nobody in Asia particularly wanted. But they did want freighters. And Europeans could break into Asian trades by offering their ships as freighting vessels for existing commerce and that’s really the basis of the Portuguese breakthrough. The trips they made bringing spices back to Europe were tremendously important but they weren’t very important for the world because the scale of that trade was always negligible. The real importance of the Portuguese presence within the Indian ocean was just that – it was presence within the Indian ocean breaking into this immensely rich world from which Europeans had previously been largely excluded.

The first art world superstar?

By Giulia Bartram, curator, British Museum

��

By the year 1515, when the extraordinary animal known as a rhinoceros was despatched by the governor of Portugese India, Alfonso d’Albuquerque, to King Manuel I in Portugal, Albrecht Dürer was, through his printmaking skills, an international star of the art world.

He had established his reputation in the 1490s, by publishing large, elaborate woodcuts and engravings which showed a technical virtuosity and degree of sophistication that appealed to a new type of audience. Dürer effectively created a market for print collectors that did not exist before. The quality of his woodcuts of the Apocalypse and Passion of Christ and of his engravings such as Adam and Eve, Melancholia and Knight, Death and the Devil, all clearly signed with his trademark AD monogram, were sold at trade fairs and through Dürer’s agents across Europe. They even attracted the attention of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian, who commissioned Dürer to produce one of the largest prints in existence, the Triumphal Arch which was also produced in 1515.

The rhinoceros had not been seen alive in Europe for over 1,000 years and must have seemed almost mythical to contemporaries. It was primarily known from the Roman author, Pliny, who described its animosity with the elephant in his Natural History, written shortly before his death at the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79.

Dürer lived and worked in the central European city of Nuremberg and although he never saw this creature himself, he was shown a description (given above on the print) and sketches sent from Lisbon after the animal’s arrival. Dürer’s prints and drawings of horses, dogs and deer show that he had a natural affinity with animals; and his incomparable skill as a portraitist has come to the fore in this memorable image. What he did not know of the physical appearance of a rhinoceros is more than compensated for by his imagination.

The captivating effect this belligerent creature has had on admirers lasted well into the nineteenth century, mainly because so many thousands of impressions of the woodcut and copies of it were circulated across Europe.

Transcript

Broadcasts

- Fri 17 Sep 2010 09:45���˿��� Radio 4 FM

- Fri 17 Sep 2010 19:45���˿��� Radio 4 FM

- Sat 18 Sep 2010 00:30���˿��� Radio 4

- Fri 13 Aug 2021 13:45���˿��� Radio 4 FM

Featured in...

![]()

Art—A History of the World in 100 Objects

A History of the World in 100 Objects - objects related to Art.

Podcast

-

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, retells humanity's history through objects