The Green Book – A Visual Journey

Jonathan Calm, artist and assistant professor of photography at Stanford University, travelled across America's southern states with Alvin Hall, for .

The image of the open road and the idea of free travel across a boundless land of opportunity lies at the core of the American spirit. The struggle for civil rights has historically revolved around overcoming limitations of mobility based on racial prejudice. Major activist efforts like the 1962 Freedom Rides, or their little-known 1947 predecessor, the Journey of Reconciliation, carried the powerful symbolism of mixed-race groups of passengers who sat together on bus rides through the South to protest segregation. The Green Book guides, published between 1936 and 1967, were about different, far less chronicled right of African-American mobility: the right of upwardly mobile black citizens to travel with a sense of dignity as well as security with the knowledge of welcoming accommodations and services had been mapped out for them.

As locations I had only read about in The Green Book came into focus, I realized that our words and pictures go beyond merely documenting the safe places for travellers of colour during the last three decades of the "Jim Crow" era (1890-1965). Our words and pictures also include the forbidding narrative of the South from that time as well as today’s racial realities. My grandfather and grandmother occasionally talked about road-side confrontations with Southern racism, but mostly kept those stories to themselves for fear of unduly burdening the next generation – or maybe because words just couldn't do justice to the all of the dimensions of experience.

I vividly remember that when I got my driver's licence, I was clearly told how I should and shouldn't behave as a young black male when interacting with law enforcement: never pass a police car ahead of you, make sure you don't speed, be sure your tail lights are working and know the company in the car with you in case you get pulled over, and if so, keep both hands on the wheel and tell police what you are doing without making any sudden movements.

As Alvin, producer Jeremy Grange and I drove through the South looking for places featured in the Green Book and people who remembered them, I sat in the back seat, sometimes listening to Mahalia Jackson's voice recorded decades ago. The lyrics about the delayed gratifications that would be rewarded in heaven, made me reflect on the slowness of the South, and how it can feel like a place where time seems to have come to a standstill. So many of the images I saw out of the car window reminded me of a photographs from another era; yet many of the sites we are searching for are gone. What remained was frequently only street names, some surviving buildings and architectural fragments bearing witness to formerly thriving black businesses and communities. Such deterioration feels like a dispiriting testament to the lack of opportunity beyond low-wage, fast food types of jobs. The safe havens have been wiped out irrespective of the purportedly simple, cheap and easy way of living they support.

Signs and plaques bear witness to the people and places that have disappeared, expressing a geography of absence. Some historical landmarks still stand, like the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where the 1965 Bloody Sunday Civil Rights march from Selma to Montgomery took place. Others, however, are now long-unoccupied decaying properties or empty, weed-covered lots. Some sites look like surreal time capsules. The interior of a shop in Jackson, Mississippi on North Farish Street that belongs to the man whose father invented the pig ear sandwich, looks like an art installation organised around the image on an old TV, with a jukebox, Pepsi machine and ubiquitous wood panelling completing the still life. Even Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, preserved behind glass as it looked at the time of his death, appears neatly detached from the reality surrounding it, like an eerie tableau.

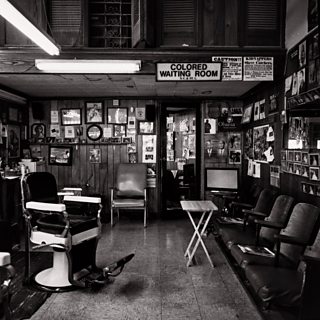

A living, evolving memorial to the halcyon days of the civil rights movement, as well as a shrine to the global black experience, is the Malden Brothers Barbershop in Montgomery, Alabama. (The memorabilia adorning its walls range from a "Colored Only Waiting Room" sign to pictures of President Obama and the late Nelson Mandela.) This is where Dr. King began having his hair cut the year before he led the 1955 Bus Boycott against racial segregation on the city's public transit system. The shop occupies the basement of the four-story Ben Moore Hotel building at the intersection of High and South Jackson, once a vibrant hub of African-American activism and social life. Today, the hotel has fallen into disrepair, with only the sign of the Majestic Cafe on the first floor attesting to its former glory, when it was one of the important crossroads of local culture and commerce.

Of all the Green Book locations we saw and first-hand recollections of these places we gathered during the trip, maybe the most poignant Southern monument to the hidden and missing is held in the urn-like gallon jars of the Soil Collection Project, an extraordinary undertaking by the Equal Justice Initiative and its founder, Brian Stevenson. The Project is a growing exhibit of earth samples collected from every location in Alabama where a person was lynched. The colour and texture of the dirt in each jar immediately evokes thoughts of the variety and colours of Black people’s complexions. This wall of jars, labelled with the names of the people lynched, makes for an imposing and moving sight. It symbolically transports the minds of those looking at it, especially African-Americans of different generations, from a discourse about historical trauma to thoughts about what has been physically lost and what remains to commemorate that loss. From this perspective The Green Book, this radio programme about it, and the photographs I’ve assembled are not just about the places, they are also about the people who gave these places life, but who are now gone.

The Green Book is broadcast at 8pm on .

Further reading and listening on Civil Rights

-

![]()

The US Supreme Court orders schools to become racially mixed.

-

![]()

Soul Music explores a song that has become synonymous with the American Civil Rights Movement.

-

![]()

Craig Charles outlines the history of America's greatest protest songs.

-

![]()

A collection of programmes and content marking Black History Month.