Mysterious and mischievous medieval doodles

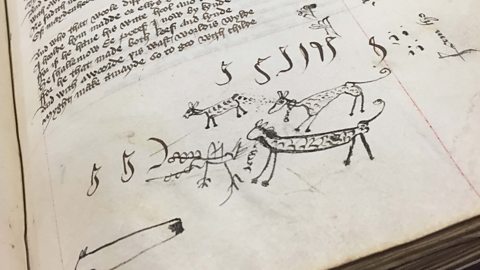

Radio 4’s Knight Fights Giant Snail explores the world of medieval ‘marginalia’ - the absurd and outlandish doodles found in the margins of medieval prayer books and secular manuscripts.

Whilst marginalia might sound like a niche amusement, Dr Alixe Bovey investigates how images of walking fish, knights fighting snails, murderous rabbits and mischievous monkeys can give us insight into the beliefs, inventions and ideas in society at the time.

-

![]()

Knight Fights Giant Snail

The images in medieval margins range from the playful to the bizarre.

What exactly is marginalia?

Marginalia are essentially cartoons that were found in the margins of prayer books and other manuscripts in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, when books were bound by hand and the pages had a large amount space around the intended text. As Dr Bovey notes, the images were “often funny, sometimes rude, obscene or absurd” and had “no meaningful relationship to the texts they accompany.”

Just how absurd are we talking?

Dr Bovey explains that medieval illuminators “found humour and pathos in mixing things up: comedy next to tragedy, obscenity next to devotion, monsters next to heavenly creatures, order next to disorder.”

Marginalia images were often funny, sometimes rude, obscene or absurd.

There’s a lot of inverting the natural order between humans and animals, for example rabbits hunting a man, and a cow milking a woman. Meanwhile, among weird and wonderful animal creations are a serpent whose tail turns into a tree; dogs walking along on their hind legs playing bagpipes; a snail with the head of a lynx (among other wacky gastropod representations); monkeys baring their bottoms at funerals while monks are giving the service; goats with pink horns and men with fish tails and wings. Among other highlights discussed is a figure that looks like Yoda and nuns picking penises from a tree.

The mystery of the medieval doodle

Can you figure out what these medieval doodles or marginalia depict?

Where did marginalia originate?

Professor of the History of Medieval Art at the University of Cambridge, Paul Binski believes that the first examples of marginalia started in the university towns, in particular in Oxford and Paris. The university towns were home to the book markets, but also places with, as now, “immense concentrations of raucous young people who have student humour.”

Why were these marginalia created?

Professor Binski links the rise of marginalia to the expansion of bureaucracy within church and state governments. “You have an immense expansion of people who wield pens and sit in offices, and they get fed up”, he explains. “It first started in the papal administration of Pope Innocent III where you have a huge secretariat, room after room full of people copying out boring papal documents. Young men who have Latin and are bored sick of the tedium of bureaucracy start to draw these little marginal drolleries – and the Pope doesn’t mind them.”

-

![]()

Marginalia

Would you write in the margins of books? Simon Armitage travels to the edge of the page to explore marginalia.

Did anyone complain?

Senior Lecturer in Medieval History, Damien Kempf notes that there is very little sign of censorship, and Dr Bovey notes that the dissenting voices were few and ignored.

Was there any meaning behind them?

As political cartoonist, Martin Rowson notes, lowering tone appeared to be the agenda. As, to what end, there’s a strong likelihood that satire was the intent.

Sarah J Biggs from the Department of Medieval Manuscripts at the British Library says that such marginalia reflect: “the idea of mocking the powerful, mocking the clergy, mocking everybody actually.”

She adds: “We have very compartmentalised lives today, but medieval people lived in a world where they were constantly surrounded by death and disease and birth, and other people’s poo and their own smells. These manuscripts reflect that, they include all of life.”

Why do people draw?

Drawing is something we all do unselfconsciously as children before we learn to write.

Are there any other schools of thought?

Quite a few, yes.

Sonia Drimmer, Associate Professor of Medieval Arts at the University of Massachusetts Amherst suggests that the playful element was designed to be an exception to the rule. She describes how carnival season, preceding lent, was a time when people would briefly reverse traditional roles, dress like monsters, “behave like devils and play loud music.” Some commentators saw this as a pressure valve, while others saw it as a way of reaffirming the conventional order. “It points to those activities as against the grain,” says Drimmer, “and you only get to do them once a year, or for that moment, or in the margins of the book.”

Finally, in the programme at least, Emma Dillon, Professor of Music at Kings College, London, suggests marginalia was a kind of ‘health warning’. She recounts a tale by Caesarius of Heisterbach about a group of fellow monks losing themselves in song - all of sudden the devil appears and collects all of their superfluous notes. The moral of the story was: don’t get distracted.

How drawing can improve your memory

A look at the results of a new study about what effects drawing can have on your memory.

“There was huge anxiety among theologians of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries about the dangers of distraction, Dillon says. “So another way to understand these margins maybe as part of that, showing what distraction looks like.”

Dr Bovey adds that marginalia could even simply have been an “indexical function”, helping the reader to find or remember a phrase.

What happened to marginalia?

Sarah J Biggs explains that the “return to classical ideals and classical modes of representation” of the Renaissance heralded the beginning of the end of marginalia. While the definition of marginalia to include notes, rather than images, applies to writers such as Edgar Allan Poe and Mark Twain, we’ve not seen a return to these fascinating images.

The PC game Inkulinati is described as, "a turn-based strategy with medieval animals inspired by 700 years-old real-life medieval marginalia."

However, there is a very recent homage to the phenomenon – the PC game Inkulinati, described as, "a turn-based strategy with medieval animals inspired by 700 years-old real-life medieval marginalia." Inkulinati's developers, Yaza Games, encourage players to, "lead your illustrated animal army on the pages of medieval books. Create your own bestiary, duel with medieval celebrities and go on wild quests, encounters and challenges."

One has to wonder what Pope Innocent III would have made of this!

More from Radio 4

-

![]()

Knight Fights Giant Snail

The images in medieval margins range from the playful to the bizarre.

-

![]()

Why it鈥檚 good to fidget

Why some of us repeatedly click pens, doodle and knee jiggle.

-

![]()

12 fascinating facts about dots

Have a gander at these fun facts about the shape that we are, quite simply, dotty about.

-

![]()

In Our Time: Medieval

Browse the Medieval era within the In Our Time archive.