Poet, playwright, muse: Celebrating Shakespeare at the 成人快手 Proms

Whether in songs or dances, serenades or marches, Shakespeare’s plays suggest music at every turn.

Scholar Stanley Wells explores how sound permeates word and why Shakespeare’s characters and scenarios have proved an enduring inspiration for composers across the centuries.

-

![]()

The World's Greatest Classical Music Festival - find out full details and book tickets.

-

![]()

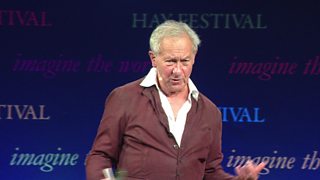

A pioneering partnership produced by the 成人快手 and British Council with partners The RSC, Shakespeare's Globe, BFI, Royal Opera House and Hay Festival.

We cannot say for certain that these words, spoken by Lorenzo in The Merchant of Venice, reflect its author’s own opinions but Shakespeare undoubtedly knew a lot about music and cared greatly for it.

The man that hath no music in himself, Nor is not moved with concord of sweet sounds, Is fit for treasons, stratagems and spoils [鈥 Let no such man be trusted.Lorenzo, The Merchant of Venice

His plays are full of cues for fanfares and marches, dances and serenades; music heightens emotional situations such as the suffering of Richard II in his prison cell and the reunion of King Lear with his daughter Cordelia; it is often associated with the supernatural, as with the Witches in Macbeth and the spirit Ariel in The Tempest (perhaps the most musical of all the plays); it accompanies the apparent resurrection of Thaisa in Pericles and of Hermione in The Winter’s Tale; Ophelia in her madness sings snatches of old songs; in Othello Desdemona’s singing of the Willow Song provides a poignant moment of repose before her murder.

Dislike of music is a symptom of malignancy in Shylock and Iago

Shakespeare writes tender songs for Feste in Twelfth Night and for Lear’s Fool, both with the singing actor Robert Armin originally in mind. Even the monster Caliban, in The Tempest, knows that Prospero’s island is ‘full of sounds and sweet airs that give delight, and hurt not’. In Twelfth Night and in The Tempest, raucous music underpins drunken revels, and dislike of music is a symptom of malignancy in Shylock and Iago.

Lorenzo speaks in blank verse, the standard form for Shakespearean drama, made up of 10-syllabled iambic pentameter lines, ‘blank’ in the sense that it is generally unrhymed, though rhyme may be used too. But Shakespeare never uses blank verse for words that he intends to be sung, which are always set off from the surrounding dialogue by being written in lyric measures, often marked by repetitions and refrains, and with a relatively low density of meaning.

Shakespeare knew that verse meant to be set to music benefits from simplicity of expression and can accommodate repetitions – as in these words sung by the page boys in As You Like It:

It was a lover and his lass, With a hey, and a ho, and a hey-nonny-no, That o鈥檈r the green cornfields did pass In spring-time, the only pretty ring-time, When birds do sing, hey ding-a-ding ding, Sweet lovers love the spring.As You Like It

This helps to explain why few of the great musical settings of Shakespeare’s words draw on the dialogue of the plays. There are exceptions, such as Vaughan Williams’s ravishing Serenade to Music, which sets Lorenzo’s speech from The Merchant of Venice quoted at the start of this article, but there the music is lyrically rhapsodic rather than dramatic, reflecting the ‘soft harmonies’ of the verse, and casting the words into second place. Among the few outstanding English operas based on Shakespeare, Benjamin Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is unusual in making few changes other than cuts to the original dialogue; whereas Thomas Adès’s The Tempest has a libretto that strips Shakespeare’s words to the bone, turning even long speeches into brief verses resembling the lyrics of his plays.

Sadly, although some of the greatest composers of Shakespeare’s time, such as Thomas Morley, Robert Johnson and John Dowland, wrote for the theatre, very little original music for his plays survives. On the plus side, however, this has stimulated many composers of later periods – as various as Mendelssohn, Arthur Sullivan, Erich Korngold, William Walton and Patrick Doyle – to write new music for the stage and, in more recent times, for films. Changing staging methods call for new styles of music, so that for example Mendelssohn writes a wedding march for A Midsummer Night’s Dream lasting some seven minutes for an episode which in Shakespeare’s theatre would have been far shorter.

Shakespearean drama – with its high passions, its soliloquies and mad scenes, its dances and battles and formalised conversations, its love scenes and lyrical interludes, and even its comic set pieces – has much in common with opera and indeed has exerted a profound influence upon operatic conventions. Ophelia’s musical mad scene is surely the origin of many bravura set pieces in the operas of composers such as Bellini, Donizetti and Ambroise Thomas, and even of the mad episode in Britten’s Peter Grimes. Mozart is said to have been contemplating an opera based on The Tempest late in his life – what a loss was there! Rossini’s Otello, with three virtuoso tenor roles and a lovely setting of Desdemona’s Willow Song, would be better known than it is had it not been eclipsed by Verdi’s late masterpiece.

Ophelia鈥檚 musical mad scene is surely the origin of many bravura set pieces

Verdi had already written a Macbeth, with a wonderfully eerie setting of the sleep walking scene. His final opera, Falstaff, based mainly on The Merry Wives of Windsor but also incorporating Falstaff’s great ‘honour’ soliloquy from Henry IV, Part 1, has similarly overshadowed Otto Nicolai’s charming The Merry Wives of Windsor, known, at least in the UK, mainly by its overture. Verdi and Britten contemplated writing operas based on King Lear but didn’t get round to this daunting task. Debussy began sketching some incidental music for the play, but he too soon gave up.

Hector Berlioz was one of Shakespeare’s most passionate admirers. He fell in love simultaneously with Shakespeare and the actress Harriet Smithson, whom he later married, when he saw performances given by a company performing in English (which he didn’t understand) in Paris in1827. One result was a string of great if eccentric compositions, including a concert overture to King Lear; a funeral march for Hamlet which calls for a large orchestra along with a wordless chorus; an opera, Beatrice and Benedict, based on Much Ado About Nothing, whose overture dazzlingly encapsulates the lovers’ battles of wit; and, greatest of all, the dramatic symphony Romeo and Juliet, at the heart of which lies the wordless but pulsatingly beautiful Love Scene. Typically, Berlioz picks out plums from the story without attempting to reflect the play’s structure.

Greatest of all, the dramatic symphony Romeo and Juliet...

Tchaikovsky’s much-loved fantasy-overture inspired by the same play, however, follows the drama’s main sequence of events from the clashing swords of the opening bars through the romance of the lovers’ meeting to the subdued pathos of their deaths. Somewhat similarly, Edward Elgar’s symphonic study Falstaff movingly follows the character’s fortunes through the Henry IV plays to the report of his death in Henry V, with two retrospective orchestral interludes recalling Falstaff’s earlier days.

Shakespeare adopted many of the conventions of the popular theatre of his time – comic routines, song interludes, dance episodes – and these are often reflected in musicals based on his plays. One of the most successful of all adaptations of Romeo and Juliet is Leonard Bernstein’s jazz-inspired West Side Story, with its exhilarating dances; and Cole Porter’s Kiss Me, Kate, based on The Taming of the Shrew, has as its hit number the catchy ‘Brush up your Shakespeare, / Start quoting him now’, with its witty puns on the titles of the plays. There is even a rock Othello.

Jazz composers have responded to Shakespeare too. Sweet Thunder, a sequence of music by Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn commissioned by the Stratford (Ontario) Festival in 1956, sets lyrics associated in various ways with the dramatist, and in 1963 Ellington composed incidental music for the Festival’s production of the rarely performed Timon of Athens.

John Dankworth is another jazz composer who has set Shakespeare; the 2007 Prom entitled ‘From Bards to Blues’ featured Shakespeare settings by both Dankworth and Ellington.

To paraphrase Falstaff, Shakespeare was not only musical in himself, but over the centuries has also been the cause that vast quantities of great music have come into being, inspired by the structure of his plays, the passions of their characters, their lyrical beauty and their emotional power.

(This article was first published in 成人快手 Proms 2016: The Official Guide)

成人快手 Proms 2016: Shakespeare

-

![]()

Tchaikovsky: Fantasy-Overture 鈥楻omeo and Juliet鈥�

-

![]()

Faur茅: Shylock

-

![]()

Tchaikovsky: The Tempest

-

![]()

Prokofiev: Romeo and Juliet 鈥� excerpts

-

![]()

Berlioz: Beatrice and Benedict 鈥� overture

-

![]()

Berlioz: Romeo and Juliet

-

![]()

Debussy, orch. Roger-Ducasse: King Lear 鈥� Fanfare d鈥檕uverture; Le sommeil de Lear

-

![]()

Sibelius: The Tempest 鈥� Prelude

-

![]()

Duke Ellington: Such Sweet Thunder

-

![]()

Music for and inspired by Timon of Athens, The Tempest, A Midsummer Night鈥檚 Dream (Purcell, Locke, etc.)

-

![]()

Shakespeare choral settings by Johnson, Morley, Nico Muhly and Huw Watkins

-

![]()

Berlioz: Overture 鈥楰ing Lear鈥�

-

![]()

Shakespeare: Stage and Screen

-

![]()

Mendelssohn: A Midsummer Night鈥檚 Dream 鈥� overture and incidental music

-

![]()

Tchaikovsky: Fantasy-Overture 鈥楬amlet鈥�

-

![]()

Hans Abrahamsen: let me tell you

-

![]()

Shakespeare settings by Purcell (arr. Britten) and Quilter

-

![]()

Vaughan Williams: Serenade to Music; Jonathan Dove: Our revels now are ended

Proms Extra (free events)

-

![]()

Colonel Tim Collins OBE discusses the depiction of soldiers and war in Shakespeare鈥檚 work

-

![]()

Richard Chartres, Bishop of London, discusses the place of religion in Shakespeare鈥檚 works

-

![]()

Readings from Shakespeare and his contemporaries including the sonnets and famous speeches from Romeo and Juliet

-

![]()

Geoffrey Robertson QC contends that Shakespeare must either have studied at the Inns of Court or have been close friends with those who did

-

![]()

Veteran sailor Sir Robin Knox-Johnston talks about the sea, shipwrecks and sea captains depicted in Shakespeare鈥檚 plays

-

![]()

Michael Pennington discusses how the playwright portrays the profession he knew best

-

![]()

The Herdwick Shepherd, James Rebanks, talks about his profession as depicted in Shakespeare鈥檚 plays and how it has changed over 400 years

-

![]()

Explore the 成人快手 Proms Shakespeare collection

-

![]()

The 成人快手 Proms investigate how Shakespeare inspired 400 years of music

Watch Sound of Cinema recorded at the King Edward VI School in Stratford-upon-Avon (Shakespeare's school) on 23rd April 2016

Sound of Cinema

The 成人快手 Concert Orchestra celebrates the music of Shakespeare on film.

Discover related stories and clips

-

![]()

Music films from across Europe re-imagine Shakespeare's plays and sonnets

-

![]()

Elaborating on the recent realisation of the Bard collaborating on his plays

-

![]()

The historian has a brief turn at cabaret to help us brush up our Shakespeare

-

![]()

Find out more about Robert Armin and the rest of Shakespeare's acting company

More on Shakespeare...

-

![]()

Experience an incredible commemoration of the Bard's 400th death anniversary with videos feauring David Tennant, Ian McKellan, Adrian Lester and more

-

![]()

A great collection of actors, authors, writers, including Russell T Davies, Germaine Greer and Salman Rushdie, celebrating the Bard at the arts and literature gathering

-

![]()

Watch some of the most memorable Shakespeare speeches, as chosen by the RSC, featuring Peggy Ashcroft, Patrick Stewart, Vanessa Redgrave and more

-

![]()

From the Bard's influence on pop music to his face appearing on a 拢20 banknote, discover more unorthodox and unusual tales of Shakespeare from past to present