A man out of time β why Parry's music and ideas were at odds with his image...

Perhaps it's the name that does it: Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry.

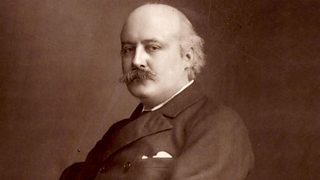

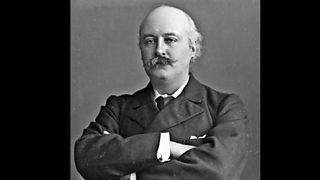

It's a mouthful of a moniker, evoking the image of a dusty Victorian patriarch, stiff-backed and disapproving. The images we have of Parry do little to dispel this preconception: they are variations on a theme, in which only the age of the subject changes.

There he is, moustache overflowing, handkerchief in his top pocket, arms folded, a proud man of his era.

Only in a couple of these photographs does his face betray something else, a softness and a shadow of mirth: indications that the starched and fusty idea of Hubert Parry handed down to us – via the ceremonial pomp of I Was Glad, the patriotic surge of Jerusalem and our received idea of what a gentleman of his time was like – might not offer the full picture of the man and his intentions.

"The Land Without Music"

It's fitting that Hubert Parry was born in 1848, the year of revolutions in Europe.

For Parry was to became a catalyst for the reinvention of British music, which had lain in the doldrums for over a century. His work as composer, writer and teacher was an ambitious corrective to a German musical polemicist's dismissal of Victorian Britain as "A Land Without Music".

In an age of piety, Parry was in fact a Darwinist, a liberal humanist and a sceptic.

He was a supporter of women's suffrage, he expressed sympathy with pacifism during WW1 and was a passionate advocate of music for all. He became Director of the Royal College of Music in 1895 and inspired generations of younger musicians who took up his challenge to make British music great again.

Hubert Parry grew up amid the imposing surroundings of Highnam Court in Gloucestershire; his life seemingly set on a smooth course, given the silver spoon he was born with. His was an untroubled path from the family estate to Eton, then Oxford and beyond. Yet the young Parry was a rather lonely boy and his choices were unusual. Discouraged by his family from following a career as a composer, he began his working life at Lloyd's Register, only later dedicating himself wholly to music.

"

Prometheus Unbound

Parry’s first musical revolution came in 1880, with the premiere of Scenes from Prometheus Unbound, an ambitious choral work of wide scope and poetic ambition, based on Shelley's poem.

Surprisingly it was considered too avant-garde for many; for others it marked a kind of Year Zero in English music. Two years later the critic Joseph Bennett would write that Parry's work gave “capital proof that English music has arrived at a period of renaissance”. Even so, the special significance of Prometheus Unbound has not been matched by its performance record.

It’s rarely heard these days, and the same can be said of so much of Parry's music. A thick layer of dust seems to have settled over his life’s legacy. There are many lost gems waiting to be rediscovered.

Moral Idealism

Parry wrote five symphonies, a wide array of choral compositions and numerous chamber works.

With no British predecessors to inspire him, he took his musical inspiration from German musical titans like Brahms and Schumann – bringing a new, English sensibility to the late Romantic style.

His English Lyrics broke new ground in tapping into the loneliness of his personal life, while the choral cycle Songs of Farewell drew on thoughts of his own mortality as he grew older – click on the clip to hear Donald Macleod discuss the cycle.

Despite lifelong ill health, Parry was energetic and active, ever-productive, but unsettled too, as his biographer Jeremy Dibble suggests: “Below the surface he was a nervous, introspective man, whose music, with its melancholy inclinations, looked to express a yearning for a new, moral idealism in which democracy would help to raise the standard of a self-improving society.”

The popular hymn Repton was drawn from Parry’s 1887 cantata Judith and became a staple of church worship in this country.

An irony perhaps, since by the time Judith was commissioned, the man who had been brought up in a very devout household and married into one which was equally religious, had, if not exactly lost his faith, certainly become opposed to organised religion.

Beginning in 1903, Parry began to express his radical personal philosophies in a series of experimental works that we call “ethical cantatas”. It was a brave, and not wholly welcomed, diversion for an audience who idolised the sacred oratorios of Handel and Mendelssohn.

Here is Parry's popular choral work Blest Pair of Sirens, recorded using binaural audio, and performed by the ³ΙΘΛΏμΚΦ Singers and the Symphony Chorus and Orchestra conducted by Sir Andrew Davis for the ³ΙΘΛΏμΚΦ Proms 2018.

βAnd did those feet in ancient time / walk upon England's mountains green?β

Donald Macleod on Jerusalem

Part of a 1958 recording of Paul Robeson singing Parry's Jerusalem.

The words belong to William Blake, but they are wedded to Parry's most enduring composition, the choral hymn Jerusalem, which has become something like an English national song.

Parry wrote it in 1916 at the behest of his friend, the poet laureate Robert Bridges, as a piece that would lend itself to rousing mass singing, a tonic to wartime resolve. The first performance, at the Queen's Hall, just yards away from the future ³ΙΘΛΏμΚΦ Broadcasting House in London, was a rousing success.

But Parry, never an uncritical patriot, was uncomfortable with the bellicose flag-waving that the song provoked. He might not have approved of its now traditional place at the climax of the Last Night of the Proms.

Donald Macleod on Parry's death

Parry's last public performance and his death shortly afterwards.

In October 1918, just a matter of weeks before the end of the First World War, Hubert Parry died of Spanish Flu and septicaemia, aged 70. Parry’s reception and reputation has greatly faded in the century since his death.

The great composers who arose in his wake brought British music to its full flowering in the 20th century, leaving Parry’s music seemingly emblematic of a Britain we left behind long ago. But Parry himself was no period piece. In many ways he was a man out of time.

His restless questing and unconventional life offers a fascinating lens through which we can rediscover his wonderful music today.

Download Donald Macleod's Composer of the Week on the life and work of Hubert Parry.

Jeremy Dibble on Hubert Parry's Death

Parry's waning health and eventual death.

-

![]()

A Portrait of Parry

Simon Heffer argues for a reevaluation of Parry not only as a composer, but as a writer and educationalist.

-

![]()

What is the strange power of Jerusalem which makes strong men weep?

-

![]()

Composer of the Week - Hubert Parry podcast

In this centenary year, Donald MacLeod explores the life and work of Hubert Parry.

-

![]()

Composer of the Week - Hubert Parry

Donald Macleod explores the life and work of Hubert Parry.