How Ireland was electrified

Having mains electricity was a novelty in many Irish households as recently as the 1960s.

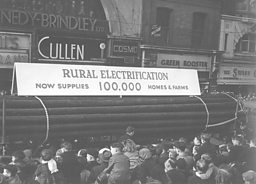

The Rural Electrification Scheme, which brought power to small towns and villages throughout the country for the very first time, only got underway in 1946.

It took nearly two decades to complete, and was a huge undertaking for Ireland’s electricity board, the ESB.

“The ESB didn't carry this out by handing it over to one of the existing departments,” says Patrick Dowling, who was Deputy Director of Rural Electrification at the time of the scheme.

“They set up a separate department and we called it the Rural Electrification Office.”

Many larger places in Ireland had been given their own supply years earlier, thanks to a hydroelectric plant fed by the waters of the river Shannon in the south west of Ireland.

But the power it generated only reached major towns and cities.

And that left most of Ireland’s population off grid — at that time, 60 per cent of the population lived in towns whose populations were 1,500 people or fewer.

By comparison, well over two-thirds of households in Britain were connected by the end of the 1930s.

Many of those living in small Irish settlements felt, quite literally, like poor relations.

In the early days of the scheme, the ESB made a promotional film which portrayed people’s reaction.

In it, one woman commented: “I always wanted it [electricity], I thought we'd never get it. I've a married sister in the town, and she's had electricity in the house ever since she got married and I've always envied her.”

Building a power network to provide for people like her was a slow, laborious process, especially in a country with limited natural resources.

Thousands of miles of cable were needed — and it soon became clear there wasn’t enough wood in Ireland’s forests to make the poles needed to support the cables.

Dowling and his colleagues arranged a meeting with Finnish loggers, who they hoped could sell them more.

“When we told them that over the next 10 years, we'd be looking for one million poles they got extremely interested,” he told a documentary team in 1996.

The advent of the Rural Electrification Scheme was in part down to the work of Canon John Hayes.

Father Hayes was an influential campaigner — and founder of the Irish social movement Muintir na Tíre (Irish for 'People of the Land’), which fought for rural development.

He’d thrown his weight behind the scheme.

But having successfully lobbied for the project to get the green light, once it was up and running, Father Hayes faced a new challenge.

The ESB decided the order in which villages would be hooked up to the power grid based on the number of households that committed to pay a monthly standing charge.

A number of rival villages close to his parish — Bansha in Tipperary county — were vying to be the first in the area to be connected.

Father Hayes was having none of it.

“There was a big row about which area was first,” Dowling said.

“I’m told that in every sermon for about three months in Bansha church was about who hadn't signed up for the electricity.”

Father Hayes had to contend with another phenomenon if he was to win this battle.

Not everyone wanted to be connected.

Some were unwilling to pay the standing charge — others were suspicious of the new technology, fearing mice would chew through the wires and set the thatched roofs alight.

In the ESB promotional film about the project, one character says: “I wouldn't have a thing like that in the house. I should never feel safe in my bed at night.”

The ESB provided demonstrations of new appliances powered by electricity, such as ovens and water pumps, in an effort to persuade people like her of their benefits.