The story of The Green Book – a travel guide like no other

For black motorists in the mid-20th century, The Green Book was a catalogue of refuge and tolerance in a hostile and intolerant world.

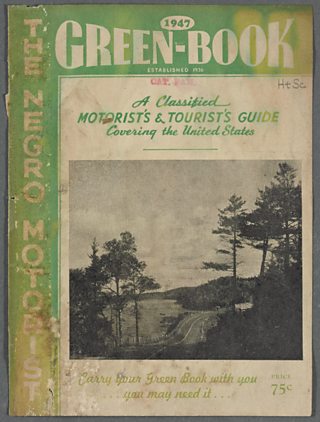

The Green Book – or to give it its full title, "The Negro Motorist Green Book" – was a quietly revolutionary publication which listed restaurants, bars and service stations which would serve African-Americans.

Alvin Hall hits the highway to document a little-known aspect of racial segregation. This is his extraordinary story…

“To compile facts and information connected with motoring, which the Negro Motorist can use and depend upon.” That was the simple goal stated by Victor H. Green, the creator of The Negro Motorist Green Book (today commonly called The Green Book). He launched the publication in 1936, a time of segregation in America and "Jim Crow" laws [state and local laws enforcing racial segregation] throughout the South, when "driving while black" was even more difficult and hazardous than it is today.

When I was growing up in the Fifties and Sixties as part of the rural “dirt poor” in the South, my family was unaware of The Green Book. We had no car and there was no public transportation except for the Greyhound bus that came along our road once or twice a week. Instead, we depended on relatives – Uncle Son, Sus’ Lizzie, Cousin Ollie Mae, Mr. Buddy Alton – who owned cars or “a piece of a car,” as they would say, to drive us to town to buy groceries and clothes, to the clinic in the local county seat, to the doctor in the city, and to visit relatives in other towns and villages. I first learned about The Green Book many years later while reading an article about traveling through the Southern US.

Earlier this year, at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York, I was able to read through many of the annual editions of The Green Book. I started by looking for locations in Tallahassee, Florida’s state capitol, only 20 miles away from the small village near where I grew up. I found a couple of hotels described as friendly to black travellers that had appeared in various editions of the guide. Later, I would discover that author James Baldwin (a personal hero) and musician Ray Charles had stayed at these hotels. Much to my surprise, the buildings (or parts of them) still stand at their original locations in the black section of Tallahassee, although they are now being used for totally different purposes.

My curiosity piqued, I embarked on a journey through the South to learn more about The Green Book and what it reveals about life in the pre-Civil Rights era. I started my travels in Tallahassee, where I interviewed people who knew a lot about the two local hotels that had once welcomed black motorists. I drove through Montgomery, Alabama; Selma, Alabama; Jackson, Mississippi; and Memphis, Tennessee, concluding my journey in St. Louis, Missouri.

During the Jim Crow era, black families generally took their own food with them while traveling, since they couldn't count on finding a restaurant or store where their business would be welcome. Everyone I interviewed told stories of mothers and grandmothers spending much of the day before a trip getting food ready – boiled eggs, fried chicken, corn bread (made without milk) and tea cakes (made with cane syrup or molasses)–packed neatly in shoeboxes lined with tin foil (the local name for aluminum foil) or wax paper. Coolers filled with ice were stocked with water, RC Crown Cola, Nehi Sodas, and other local brands of soft drinks.

In the course of these travels, I learned more about many of the hotels, tourist houses, restaurants, gas stations, taxi services, beauty parlors and barbershops, and funeral homes once listed in The Green Book. I also delved deeply into the history of the guide: the circumstances that prompted Victor Green, a postman who lived in Harlem but delivered mail in New Jersey, to create it; the methods he used to gather and update travel information covering every state in the US as well as parts of Canada and Europe; and the stories of the black people who relied on The Green Book as their practical guide to relatively safe motoring.

Published in April or May of each year, the book was sized to fit in a car’s glove compartment. Although The Green Book identified safe havens, it was when driving between safe havens that people were vulnerable, subject at any point to the capricious behaviour of racists of all professions and walks of life. Some of the personal and family stories people shared with me are still shocking and share similarities with some current incidents in the US today, when the dangers of driving while black have morphed into more subtle, but equally pernicious manifestations.

Meticulous planning and preparation were essential every time we travelled. I remember how my great Uncle Son made sure the car was totally prepared and filled with gas. We travelled only during the day and rarely stopped, refilling the gas tank only at specific, pre-selected stations, where we were told to be quiet and not to ask about using the bathroom or getting a drink of water. Later, the adults would find a wooded, shaded place just off the road (perhaps behind a local black church) where we could stop for a comfort break and some drinks from the cooler.

The Green Book’s name changed over the years as its listings expanded and the markets covered changed. A 1963 edition was called The Traveler’s Green Book: For Vacation without Aggravation. This edition included resorts as well as information about places in Mexico and the Caribbean. Europe would be added in subsequent years.

Until its demise in 1967 (five years after Victor Green's death), The Green Book remained true to its goals. Green himself believed that the passing and implementation of the landmark Civil Rights of 1964 would bring “motoring without aggravation” for black Americans. I can’t help but wonder what Victor Green and the black motorists who relied on his guidance would say if they could see the realities of life on the streets, roads, and highways of America today, some 50 years after the passing of The Green Book.

The Green Book is broadcast at 8pm on .

Further reading and listening on Civil Rights

-

![]()

The US Supreme Court orders schools to become racially mixed.

-

![]()

Soul Music explores a song that has become synonymous with the American Civil Rights Movement.

-

![]()

Craig Charles outlines the history of America's greatest protest songs.

-

![]()

A collection of programmes and content marking Black History Month.