Bilbao's Guggenheim Museum celebrates its 25th anniversary

- Published

The museum is celebrating its 25th anniversary

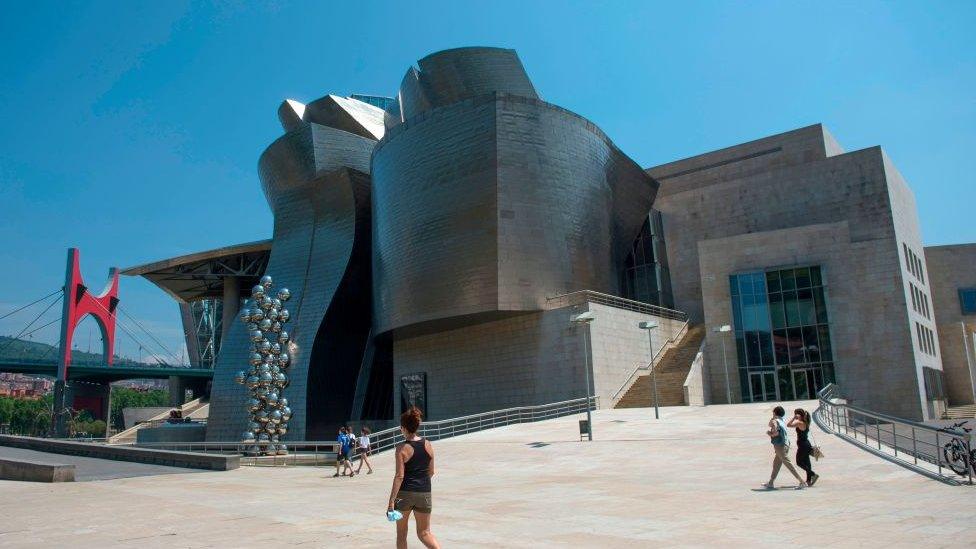

As he gazes at the eccentric, titanium-plated angles of Bilbao's Guggenheim Museum, Francisco Mulero, a tourist from Spain's Canary Islands, explains why he admires the building.

"It's spectacular," he says. "Its exterior has the appearance of a ship sailing on waves and the inside of it has these infinite curves."

He adds: "I've travelled all around the world and this is something in my own country which I just had to see."

As it celebrates its 25th anniversary, the museum's success can be seen in the number of visitors it draws: around a million each year on average. And over the last quarter century, the Guggenheim has become a major hub of modern art, hosting works by artists from its home Basque region as well as international giants such as Andy Warhol, Jackson Pollock and Alberto Giacometti.

But the museum's greatest legacy is arguably the broader impact it has had on the northern Spanish city that hosts it, a phenomenon that has become known as "The Guggenheim effect".

Building the Guggenheim's curved exterior in the 1990s

In the 1900s, low-phosphorous iron, mined from the rolling hills nearby and transported along the Nervi贸n river, made Bilbao an industrial powerhouse. In the late 19th Century, the city supplied Britain with two-thirds of its iron ore, and in the decades that followed it provided a fifth of the world's steel.

But by the late 20th Century, decline had set in and Bilbao's image was one of industrial wastelands and pollution, while the city and its surrounding region had become frequent targets of terror attacks by Basque group ETA.

Basque writer Jon Juaristi described it as "the least hospitable city in all of Spain".

The museum initially proved controversial, owing in part to its vast cost

Thomas Krens was director of the Solomon R Guggenheim Foundation in New York, which was seeking to expand abroad. When a mooted project in Venice fell through, the plan for a new museum in Bilbao was hatched.

"The Basques came to me and asked how they could change the misconception that they were famous only for terrorism and Jai alai handball," he explained to author Paddy Woodworth. "I told them they should build the greatest building of the century."

Canadian architect Frank Gehry was commissioned to design it, on a site on the riverside.

Frank Gehry, the Canadian-born architect, designed the new building

From the start, the Guggenheim Bilbao project faced criticism, in great part due to the cost - $100m for the building alone - which was paid by the local authorities. For the Guggenheim Foundation, which was simply lending its name and artworks, the risk was considerably lower.

But the gamble paid off.

"In terms of physically, literally, cleaning up a city, that happened when they opened this museum," says Lekha Hileman Waitoller, the Guggenheim Bilbao's US-born curator. "It made the residents and the government and everybody that's in control of these decisions look towards the river."

The new, ultra-modernist structure brought tourists in large numbers. The new revenues encouraged a regeneration of the city's riverside and smart new bars, cafes and other businesses, many of them hi-tech, sprung up. There are currently six Michelin-starred restaurants in a city with a population of only 350,000.

"In a very, very short time it truly did change the entire face of Bilbao," Hileman Waitoller says of the museum.

Some 25 million tourists have come to the museum since its construction

Some believe the museum's attention-grabbing design undermines its role as a home for art. The critic Hal Foster said that Gehry had "given his clients too much of what they want, a sublime space that overwhelms the viewer".

"The building is an incredible event and that's what I've always wanted to come and see," says Eve Vanvas, who is visiting from the UK, as she leaves the museum. "There's loads of interesting art in it, but really we've come to see the building."

With 25 million people having visited the museum since it opened in 1997, Bilbao's local government and its inhabitants do not seem to be complaining, even when it's the building, rather than the art, that is drawing them.

The museum even briefly appeared in the background of the James Bond film The World Is Not Enough

Images subject to copyright.

Related topics

- Published6 September 2018