Snot bubbles and belly flops keep echidnas cool, research finds

- Published

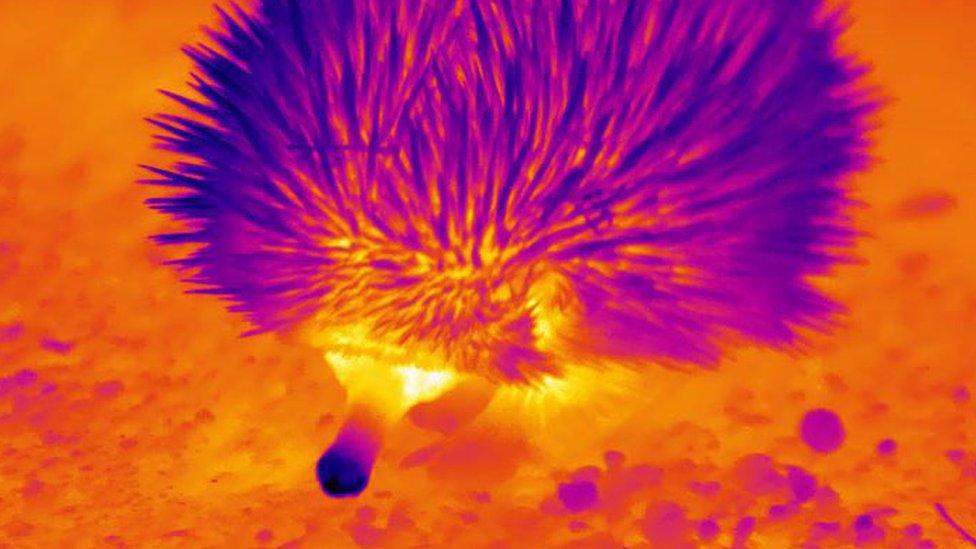

Thermal imaging shows how echidnas keep their noses - and bodies - cool

Echidnas blow snot bubbles and do belly flops to keep themselves cool in the Australian heat, new research has found.

The native animals are believed to be less tolerant to hot weather than other Australian species.

Their spines act like a blanket, and the animals cannot pant, sweat or lick themselves to cool down.

But thanks to infrared cameras, researchers have now discovered unique methods they use to release heat.

Echidnas have long been known to blow bubbles of mucus out their noses, but it was believed this was primarily to clear dirt from their snouts.

However the thermal imaging captured by researchers from Curtin University in Western Australia indicates it has a dual purpose.

The mucus bubbles burst and wet the tip of the echidna's snout, allowing evaporation to cool blood circulating just under the skin.

It is an an incredibly effective cooling mechanism, environmental physiologist Christine Cooper told the 成人快手.

"We found there's actually a 10 degree (C) difference between some parts of the body and their snout."

The idea animals use evaporation to cool their blood isn't new, Dr Cooper says, but finding an animal that uses snot for the job is, as far as she knows.

The researchers also discovered that the echidnas can shed heat by pressing their bellies and legs - which are spineless - to cooler surfaces.

As one of the rarest species in the world, one of only two types of monotreme - mammals that lay eggs - Dr Cooper says understanding how echidnas tolerate heat is essential for their conservation on a warming planet.

And this research indicates they have a better shot at survival than previously thought.

People have long assumed monotremes like echidnas are "just not very good physiologically", Dr Cooper says. The animals have a low lethal temperature, and were thought start "dropping dead" at about 35 degrees, she says.

"But in our study, we found them out and about - active, foraging and looking just fine - at ambient temperatures of 37.5 degrees."

"They are probably one of our more heat intolerance species, but we're finding that they're not as hopeless as they are supposed to be... and now we have a mechanism by how they might be managing this."

- Published24 November 2022