The self-doubter behind Thatcherism

- Published

Forty years ago a man called Keith Joseph had what alcoholics call a moment of clarity.

After years as a typical big-spending, intervene-at-all-times-of-day Conservative Cabinet minister, he suddenly changed his mind. "I have never really been a Conservative," he declared.

Electoral defeat in 1974 lifted the shutters from his eyes and allowed him to reconsider his entire approach to politics and economics. The ailing British economy, he decided, needed more enterprise and less inflation, more freedom and less government.

And so began Joseph's campaign to change the so-called post-war consensus of British politics, where ministers, unions and businessmen collaborated in the public good and used government cash to intervene in the economy to boost demand and jobs as inflation grew ever higher.

It was a campaign that ultimately helped change the way everyone thought about politics and led directly to Margaret Thatcher's transformation of the United Kingdom.

And it is a campaign that still echoes today.

Eggs and flour

When George Osborne this week spoke of his aim to fight for full employment, he was trying to slay a dragon that Keith Joseph gave life to when he argued controversially that the fight against inflation was more important than protecting jobs.

And when Graham Brady, the chairman of the 1922 committee of Conservative backbenchers, gave the Keith Joseph memorial lecture this week, he said the chancellor's Budget decision to give savers more control over their pension pots was an echo of Joseph's own desire to "give people control over their own lives, the fruits of their own labours".

My colleague Rob Shepherd and I have been re-examining Joseph's legacy for a ģÉČËŋėĘÖ Radio 4 documentary. What has struck us most is just what an unlikely revolutionary the man was.

Joseph was off-message and off-the-wall, totally unspinnable and totally lacking in political cunning. He was racked with indecision and doubt, prompted by a desire for intellectual consistency that was never satisfied by the shifting waters of politics.

Catalyst

And yet, for all the opprobrium that was poured on his head, he was trusted by opponents as much as by his supporters for his sincerity and lack of guile. And boy, did he make a difference.

We look at how Joseph gave a series of speeches that rocked the political world, how he set up the Centre for Policy Studies think-tank to promote his ideas, and how he began a seemingly endless and rowdy debate from university campus to university campus to try to influence the opinion formers of the future.

Never has so much flour and egg been thrown at a single politician. We have spoken to key players who knew Joseph in the 1970s - such as the former Chancellor Lord Lawson, the former Conservative chairman Lord Patten, the Financial Times commentator Samuel Brittan and the former head of Margaret Thatcher's policy unit Brian Griffiths.

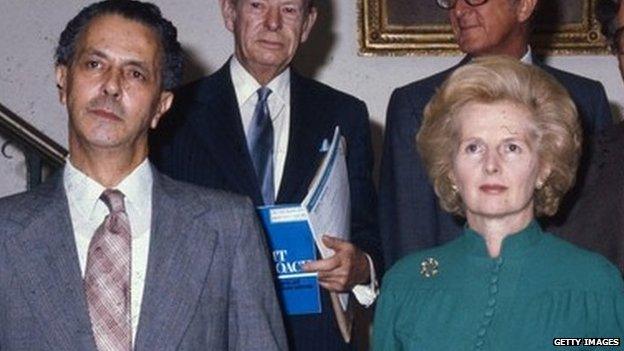

Joseph was a catalyst for change. A frontbencher freed from the burden of ambition, a conviction politician with the enthusiasm and guilt of the convert, an intellectual with the humility and oratory to articulate the views of others, a thinker gripped by self-doubt, led by a woman who had none.

Somehow, despite all his flaws, he proved that ideas and argument can sometimes make a difference.

Do catch it if you can. It is a great listen.

Thatcher's Mad Monk or True Prophet? was broadcast on Monday 7th April at 20:02 BST on ģÉČËŋėĘÖ Radio 4. It can be replayed on the ģÉČËŋėĘÖ iPlayer.