Giant iceberg A74 kisses the Antarctic coast

- Published

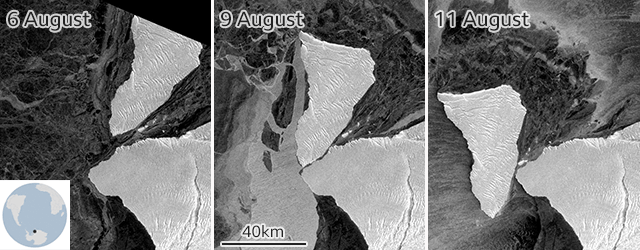

Strong easterly winds picked up the berg and pushed it past the Antarctic coast

It was the briefest and gentlest of icy kisses.

A massive iceberg that's nearly the size of Greater London was pictured by satellite this week squeezing past the coast of Antarctica.

The block, known as A74, made only the faintest of contacts. Had it been any firmer, it would probably have knocked off a similarly sized iceberg.

UK scientists were watching the icy liaison with keen interest because one of their bases is close by.

The Halley research station is currently mothballed as there is uncertainty about the way all the ice in the region might behave in the near future.

"We've been monitoring the situation very closely for the past six months because A74 has been drifting around in the same kind of area," explained Dr Ollie Marsh from the British Antarctic Survey.

"But then there were some really strong easterly winds and these seemed to trigger a rapid movement in A74 that saw it scrape along the edge of the western Brunt," he told łÉČËżěĘÖ News.

Germany's Polarstern research vessel sailed between A74 and the Brunt in March

The Brunt is what's called an ice shelf. It's an amalgam of glacier ice that has flowed off the land and floated out to sea.

It's still attached to the train of ice behind - but only just. An enormous crack, called Chasm 1, has opened up in recent years in the shelf's far-western sector. An area measuring some 1,700 sq km is on the verge of breaking free.

Many thought a big nudge from the passing A74 iceberg might be the event that made it all happen. But it didn't; or at least, it hasn't happened yet.

BAS has GPS sensors positioned on the ice shelf and on A74. These instruments report back to the survey HQ in Cambridge on an hourly and daily basis. Their data catches any sudden movements in the ice.

And although this week's contact did produce a very small rotation in the Brunt, it clearly wasn't enough to break the last 2km of ice at the tip of Chasm 1 that keeps the western shelf in place.

"So there does appear to have been a bump, and it does seem to have had a bit of an effect on the western Brunt, but not enough to cause a calving," Dr Marsh said.

The UK has had a research station on the Brunt Ice Shelf since 1957

It would be helpful to BAS if the Brunt could break soon. This would end the uncertainty surrounding the status of Halley, which sits atop the floating shelf's eastern sector.

The station is just under 20km away from Chasm 1 and scientists don't think it will be perturbed by a big calving, but they need to be sure before once again permitting year-round operations.

Currently, Halley is closed every winter as a precaution, because should the worst happen it would be very difficult and risky to try to evacuate personnel at a time of year when the weather can be awful and there is 24-hour darkness.