The humanitarian crisis in Venezuela has led to one of the largest mass migrations in Latin America’s history.

President Nicolás Maduro blames “imperialists” - the likes of the US and Europe - for waging “economic war” against Venezuela and imposing sanctions on many members of his government.

But his critics say it is economic mismanagement - first by predecessor Hugo Chávez and now President Maduro himself - that has brought Venezuela to its knees.

The country has the largest proven oil reserves in the world. It was once so rich that Concorde used to fly from Caracas to Paris. Now, its economy is in tatters.

Four in five Venezuelans . People queue for hours to buy food. Much of the time they go without. People are dying from a lack of medicines. Inflation is at 82,766% and there are warnings it could exceed .

Venezuelans are trying to get out. The 2.3 million people have fled the country - 7% of the population. More than a million have arrived in Colombia in the past 18 months.

Many of those Venezuelans have come over the Simón Bolívar International Bridge.

The bridge is about 300m long and 7m wide. It straddles the Rio Táchira in the eastern Andes, a river that snakes along the border between Colombia and Venezuela. The river bed can sometimes dry up but heavy rains soon change that.

The two small towns the bridge connects - San Antonio del Táchira on the Venezuelan side and Villa del Rosario in Colombia - are in two very different worlds.

Colombians rarely pop over the border to do their shopping in Venezuela like they used to. It’s almost entirely one-way traffic nowadays.

Every day at 05:00 Colombian time, (06:00 in Venezuela), the sound of a fence being dragged across tarmac breaks the silence in the valley and marks the opening of the bridge to pedestrians.

The queue from Venezuela into Colombia usually builds steadily overnight. When the gates open, it’s like athletes out of the starting blocks. Venezuelans can’t get over quickly enough.

Some people are stopped by guards and told to open their bags. While most do so without drama, you can see panic in some faces when people realise they are about to be caught.

With Venezuela’s economy in crisis, there’s an incentive to smuggle staples like meat and cheese into Colombia so it can be sold for higher prices. The people doing it aren’t Mr Bigs - they’re mostly just Venezuelans desperate to raise money to buy other essentials.

Venezuelans pass through migration checks on the bridge

One woman, whose meat is confiscated, wails: “What am I meant to do?” The guard replies gruffly: “This is a humanitarian corridor - you can take food into Venezuela but you can’t take it out.” And so it repeats throughout the day.

Those with nothing to declare - or perhaps just the lucky ones who aren’t stopped - walk on through. The trundle of suitcase wheels is the soundtrack of this bridge.

When you get to the end of the bridge, you reach what’s known as La Parada, or “the stop” in English. It’s a bustling community that makes its money from border trade. Market sellers, pharmacies, shops and bus companies all vying for sales from those crossing the bridge. Most of the street traders here used to be Colombians - this is after all Colombia.

But increasingly, Venezuelans have also started setting up shop here, trying to sell their wares in a country where the currency hasn’t been decimated.

Right at the end of the bridge, amid the chorus of street-sellers, one man shouts: “Who wants to sell their hair?”

In front of a metal barrier protecting the bridge, Laura Castellanos sits on a plastic stool. The 25-year-old has long wavy brown hair to the bottom of her back. She looks uneasy.

A woman is stood behind her, scissors in hand. Laura is about to lose most of her hair.

She’s nursing her two-month old daughter Paula who is wrapped up in a big fluffy blanket and wearing a stripy pink hat. She yawns as she lies patiently in her mother’s arms, unaware of the border chaos around her. Laura’s husband Jhon Acevedo is nearby looking after their two older daughters.

The hair-cutter is lifting up the top layer of Laura’s hair and cutting what’s underneath right back to the roots. She doesn’t want to talk much. It’s almost as if she’s embarrassed.

With every snip she hands a chunk of hair to another woman standing next to her. The hair buyer says nothing and looks away. It feels like a cold transaction, nothing more.

Laura is getting paid 30,000 pesos ($10) for her hair. It’ll be sold on to make extensions or wigs.

“It’s the first time I’ve done it,” she says with a mixture of nervousness and embarrassment. She’s come for the day from the town of Rubio, about an hour from the border.

Laura is selling her hair because her eldest daughter, eight-year-old Andrea, has diabetes and the family needs to raise money to pay for her insulin which she takes three times a day. The family has run out of supplies and it’s been three days since little Andrea last had her shots. Jhon’s salary as a saddler doesn’t always stretch to pay for his daughter’s drugs.

“There’s no medicine, it’s hard,” says Laura. “People are dying in Venezuela because they can’t get the medicines they need.”

After five minutes of cutting, the family heads off to find a pharmacy. At first glance you can’t tell Laura’s had most of her hair removed. The hair-cutter has left a thin layer of long hair on top to hide the truth. Laura admits she feels a bit sad.

“It will pay for something at least,” she says. Her husband Jhon says they’re looking for a “pirate” pharmacy - an informal stall that sells drugs in plastic cabinets on the street. Insulin pens will be cheaper there than in a walk-in drug store.

A Colombian “pirate” pharmacy

But on the streets around La Parada there’s no way of knowing that what they are buying is the real deal. Counterfeits abound but it’s a risk Laura and the family think is worth taking.

“There’s no insulin back home, you can’t get it anywhere,” Laura says as she eyes the best-before date on the side of the insulin pen. They pick up two dark blue pens for 8,000 pesos each ($2.65) and go on their way. That will last them nearly two months before they have to begin the search again. It’s not enough time for Laura’s hair to grow back.

Andrea with her insulin pen

On the other side of the road, not more than 10m from where Laura was getting her hair cut, 29-year-old Celene Cacique is sitting on the pavement. The mother-of-three has a black, red and white jacket with a picture of Mickey Mouse. She’s nursing her youngest - two-month-old baby Isabella who is wrapped up in a pink blanket and has a little hat on.

The sun is strong during the day but the early mornings are crisp here - wrapping up babies is a good idea. The bigger the blanket, the better.

Celene Cacique (second left) and her baby Isabella

Celene got here at 06:45, queuing for the health centre which opens at 08:00. She’s chatting to other mothers who’ve all come to vaccinate their babies. Lined up along the pavement are brightly-coloured prams and bundled-up babies.

The Colombian government opened the centre at the end of the bridge to attend to the large number of Venezuelans who are coming over the border to get vaccines.

With severe shortages of medicines and vaccines in Venezuela, and diseases that never used to be a problem are now re-emerging. Diphtheria and measles are just some of those making a come-back.

It’s the second time Celene has had to make the journey over the border.

“I came eight days ago and there were more than 120 kids,” she says. “They only let 100 in and the other 20 weren’t served. You have to get here early.”

It’s been a very tough few months for Celene. When she was just four months pregnant with Isabella, her husband was killed.

Michel worked as a lorry driver, moving cargo across the border between Venezuela and Colombia. Driving home at 10 in the evening on his motorbike, he hit a cow in the middle of the road and was killed instantly. The hospital called her at three in the morning to tell her he was in the mortuary.

“There are no lights on the road,” explains Celene matter-of-factly. “There’s so much theft, people take cables, copper, they leave nothing. It’s how they find money to pay for food.”

Venezuela’s economic problems effectively cost Michel his life.

President Maduro is the worst thing Chávez left us”

That’s a feeling shared by many. When Hugo Chávez came to power in 1999, there was hope. He was a man who championed the poor in what has always been a deeply divided society. He was a vibrant and controversial figure who wanted to lead a socialist revolution in Venezuela.

But Chavez was helped by strong commodity prices that funded his ambitious social programmes. With a fall in oil prices, President Maduro has had no such luck - and little of the charisma his predecessor had. During his leadership, the country has fallen into economic decline.

“The government does whatever it wants, it has all the power,” says Celene. “Only God can help us - it’s the only thing left.”

But Celene has a lifeline. Her mother-in-law lives in the US and sends back $500 every couple of months. With her new baby, and two older children who are four and eight, Celene is unable to work. So she relies on that money to keep her afloat. It’s money that she also shares with her sister, her brother-in-law and their baby.

Warning: This chapter contains images of injury

While pop-up health centres by the bridge can deal with less serious illnesses, 10 minutes’ drive away into the centre of the nearest city Cúcuta, the Erasmo Meoz hospital is struggling with far bigger problems.

The red-brick university hospital is creaking under the pressure.

In the emergency ward, patients are lined up in hospital beds along the wall and in front of doors. Family members are gathered around the beds, comforting their relatives.

Those who are able to are sitting on a row of plastic chairs. Other patients are in wheelchairs, attached to drips. Outside the ward, in the hospital courtyard, more people are waiting. In among the mass of people, a group of prisoners, chained by the wrists, is guided to another part of hospital for treatment.

The emergency ward has capacity for 75 beds. But there are currently 100 patients in this room. There’s hardly any space to move.

In a room off the main ward, a dead body lies waiting. Covered in a white cotton sheet, and tied tight around the neck and feet, it’s there for all to see until a member of staff finally wheels it through the crowds of beds and on to the mortuary. There’s no space or time for a peaceful exit in this chaotic hospital.

Each bed is marked with the patient’s nationality.

Ángel Escobar, 28, is one of the Venezuelans. His mother is wrapping bandages around arms which are red-raw, blistered and weeping.

Ángel Escobar

Ángel, his brother Teobaldo and their mother Cecilia recently made the journey from the city of Barinas, 350km from the border. They didn’t have the money for a bus ticket, so instead they hitched several rides, nursing Ángel and his wounds along the way.

Ángel used to be a motorcycle mechanic. Five years ago, he was fixing a bike in his workshop when a spark caused a petrol tank to explode.

“I got second and third degree burns,” he explains. “I waited in hospital in Venezuela for help - it never came.”

Instead his situation got worse. He contracted three infections in hospital and he went downhill rapidly.

The injuries he’s got look so red and recent but this has been five years of daily pain. The seeping raw skin is the aftermath of the infections, not the burns themselves.

“They didn’t treat him because they didn’t have supplies,” Cecilia explains. She says there wasn’t even an infection specialist at the hospital to help.

Ángel has got large scaly scabs on top of his skin that are slowly coming off now he’s in hospital.

His arms are deformed because of an error made by the doctors in Venezuela. In Colombia he says he’s being looked after at last.

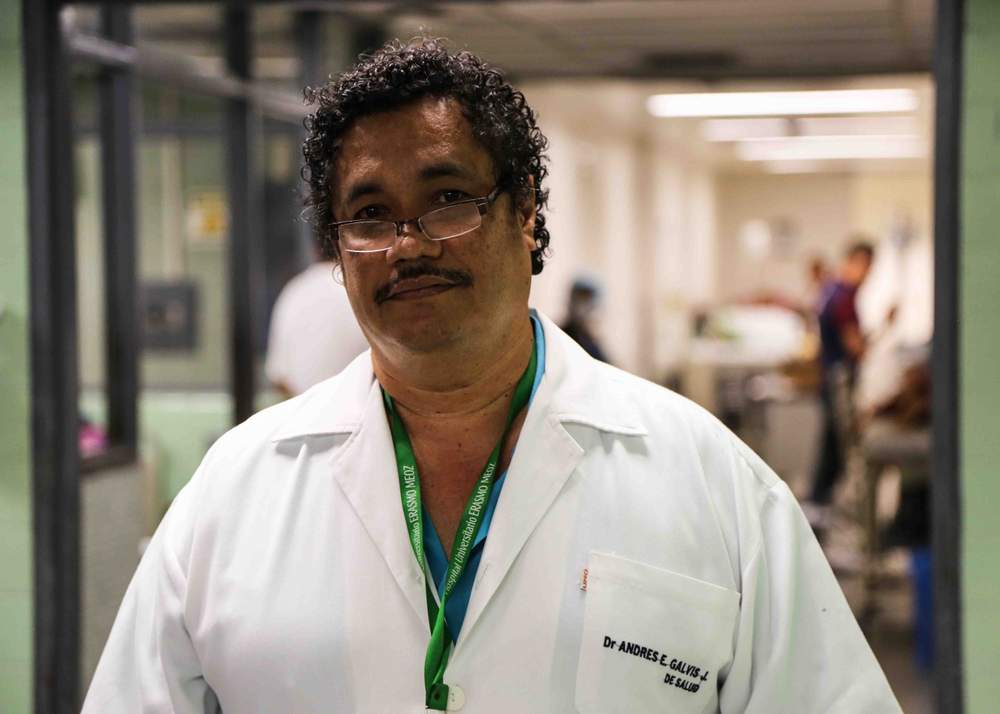

Dr Andrés Eloy Galvis Jaimes, who is in charge of the emergencies ward, says the situation is getting out of hand.

“Thirty per cent of our patients in emergencies are Venezuelans,” he says. “The national government isn’t giving us extra money. There’ll come a moment that we won’t have any more resources for anyone. That’s a real fear.”

On the Ruta Nacional 55, a main road leading south out of Cúcuta, a group of seven Venezuelans are walking along the side of the road, hoping to hitch a lift. Their belongings are in holdalls strapped across their backs or in small rucksacks. A couple have bags of water.

Eliane Pedrique took a bus from Valencia, Venezuela’s third largest city, to the border with Colombia. From there, her only option was to walk to the city of Pamplona to find work. It’s about 60km.

She’s not very well-equipped and only has sandals to wear. But with the bus fare costing 100,000 pesos ($33 dollars), it’s a luxury she can’t afford.

Eliane Pedrique and her friend walking to Pamplona

Eliane has left her two children, aged five and two, with her mother.

“I feel really sad,” she says, crying.

“There’s no way of earning money. There’s no work and the small amount you can earn doesn’t even stretch to buy rice,” she says. “You have to leave to be able to earn that little extra money so you can help.”

In Venezuela she sold ice cream and fruit on the streets. She used to sell fruit juice too but with the price of sugar going up so much, she had to stop.

She couldn’t afford nappies for her baby so instead she used bits of cloth, known as “guayucos” and then a plastic bag wrapped around it to keep the urine from leaking.

“They didn’t want me to go,” she says of her family she’s left behind. “They asked me to be careful but they have faith. We have to go forward for the sake of our children.”

She’s going to Pamplona unsure of what she will do but willing to try anything.

“If you don’t work, you don’t eat,” she says. “It’s one of the terrible consequences of this awful government we have in Venezuela. In truth, it’s hit us hard and it’s been even worse since he won the elections again in May,” she says of President Maduro.

She wants to go home in two months to give her family the money she has earned, and then return to Colombia once again.

If she goes back to Venezuela, she’ll notice some big changes. The president has overhauled the country’s currency, the bolivar, slashing five zeroes off it and pegging it to a state-backed cryptocurrency called the Petro. He also raised the minimum wage by over 3,000%.

While these changes have been justified as an attempt by the Maduro administration to rein in spiralling inflation and improve the lives of millions, few people have faith they will alter the economic realities of the country.

In the heat, the walk isn’t easy. Some people along the way have been kind, giving the walkers fruit and water. But not everyone is friendly. The day they arrived, one man gave them water with plant fertiliser in it.

On the Ruta Nacional 55, a main road leading south out of Cucuta, a group of seven Venezuelans are walking along the side of the road, hoping to hitch a lift. Their belongings are in holdalls strapped across their backs or in small rucksacks. A couple have bags of water.

Eliane Pedrique took a bus from Valencia, Venezuela’s third largest city, to the border with Colombia. From there, her only option was to walk to the city of Pamplona to find work. It’s about 60km.

Eliane Pedrique and her friend walking to Pamplona

She’s not very well-equipped and only has sandals to wear. But with the bus fare costing 100,000 pesos ($33 dollars), it’s a luxury she can’t afford.

Eliane has left her two children, aged five and two, with her mother.

“I feel really sad,” she says, crying.

“There’s no way of earning money. There’s no work and the small amount you can earn doesn’t even stretch to buy rice,” she says. “You have to leave to be able to earn that little extra money so you can help.”

In Venezuela she sold ice cream and fruit on the streets. She used to sell fruit juice too but with the price of sugar going up so much, she had to stop.

She couldn’t afford nappies for her baby so instead she used bits of cloth, known as “guayucos” and then a plastic bag wrapped around it to keep the urine from leaking.

“They didn’t want me to go,” she says of her family she’s left behind. “They asked me to be careful but they have faith. We have to go forward for the sake of our children.”

She’s going to Pamplona unsure of what she will do but willing to try anything.

“If you don’t work, you don’t eat,” she says. “It’s one of the terrible consequences of this awful government we have in Venezuela. In truth, it’s hit us hard and it’s been even worse since he won the elections again in May.”

She wants to go home in two months to give her family the money she has earned, and then return to Colombia once again.

In the heat, the walk isn’t easy. Some people along the way have been kind, giving the walkers fruit and water. But not everyone is friendly. The day they arrived, one man gave them water with plant fertiliser in it.

Edgar Centeno met Eliane on the border and they’ve joined up for moral support along the walk. Edgar is 21 with a partner and two-year-old boy back home. In Venezuela he worked in various jobs - fixing air-conditioning units was just one of his lines of work.

Edgar Centeno

“You need at least 10 jobs to be able to survive,” he says.

Colombia though is a place of opportunity. On Edgar’s back is a red, yellow and blue rucksack. They’re the colours of the Venezuelan flag. It’s a bag given to Venezuelan school children by the government but it’s become a common sight among migrants.

“My aim is not to go back empty-handed,” he says, as he walks along the road. “I made a promise to myself that I have to provide a good future for my son. Whatever happens, I need to support him.”

He doesn’t know where he’ll end up, he may carry on through South America to find the right job. He’s weighing up Peru as an option.

That dream though may not be easy to achieve. Venezuela’s neighbours are tightening their borders. Ecuador has declared a state of emergency with more than 4,000 Venezuelans crossing the Colombia-Ecuador border every day. Both Ecuador and Peru have also said Venezuelans will need passports to enter their countries - until now, an ID card had been enough.

All of the walkers blame the president for the crisis the country’s in. Edgar struggles to articulate what he feels and then comes out with it.

“He’s useless, he’s scum,” he says.

“He blames everyone apart from himself,” adds Elaine. “He doesn’t take any responsibility. He just needs to go.”

You would expect people like Eliane and Edgar, who are leaving Venezuela, to have an anti-Maduro bent. But the government maintains that the criticisms regularly levelled against it are unfair - that if it wasn’t for the US “imperialists” who want to control Venezuela, or the sanctions imposed on members of President Maduro's government and an opposition he says is hell-bent on destroying the country, then Venezuela would be in much better shape.

President Maduro and his administration often paint themselves as the innocent victims in this story of Venezuela’s decline. And they paint those who leave as deserters of the socialist cause.

Edgar, Elaine and their friends don’t want to stick around. They have ground to cover before the day ends. They cross the road and start walking towards their new - and unknown - future.

As the day goes on, the queues carry on building on the border. Hundreds of people wait in line at immigration for a stamp in their passport to make their onward journey more straightforward.

There are queues at money transfer houses where Venezuelans wait patiently to pick up much-needed funds from relatives and friends who live abroad.

And there are queues for buses - people waiting with suitcases piled up high, their entire possessions carefully packed as they head to meet their friends and families across South America.

But for every Venezuelan lucky enough to be moving on, there remain dozens who don’t have the resources to go anywhere.

Johnny, Angel and Yember are hanging around the middle of the bridge, waiting for Venezuelans to come over. Dressed in T-shirts, ripped jeans and trainers, they’ve each got a luggage trolley in hand with rope wrapped around the handles - they’re ready to tie up the heavy bags of incoming Venezuelans and help them get to the nearest bus stop.

They’re all recent arrivals from the capital Caracas, Valencia and San Cristobal. They’ve stayed by the border to earn some money before moving on. But business as a “maletero” is slow.

“The people coming from Venezuela are immigrants with nothing,” they say. They’re coming in search of money and better lives so few nowadays have the spare change for a luggage-handler.

On a good day, they earn 15,000 pesos ($5) but on a bad one, not even a cent.

They’ve given up hope of change back home. With President Maduro winning the elections, he now has another six-year term they think he’ll complete.

“If things could end peacefully, then that would be the best thing,” says Johnny. He dismisses the idea of the military turning against the president. “A coup could mean lots of people, including children, would die. But if things could end, well...” he trails off, thinking of the options.

From the bridge where the maleteros are, you can see a blue-painted cage. Inside is a figure of the Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Virgen del Carmen). She’s the patron saint of drivers and of the Army in the Andes. In a part of the world where hope is fading, faith remains strong. Fitting too that her home is an insecure frontier town, an area where soldiers operate around the clock.

A figure of the Our Lady of Mount Carmel

The virgin sits across a dirt road, in front of a metal yard where Pompilio Rincón is throwing slabs of aluminium on to a scrap heap.

He says there are lots of metal collectors that come over from Venezuela.

“Before, Venezuelans would come in their cars and trucks,” he says. Now, people are bringing metal on their backs - women and children too.”

As he chats, a young teenager in a smart checked short-sleeved t-shirt comes in with a big bag and dumps his treasure on to the massive set of scales on the floor of the warehouse. He hopes to get 1,500 pesos (50 cents) per kilo of his metal.

Scrap metal dealer Pompilio Rincón with young collector Breiner Hernández

Breiner Hernández, 15, comes from San Cristóbal in Venezuela. He goes to school in the morning and when he’s not studying, he’s looking for metal. Every few days he jumps on the bus with his bag to sell on the other side of the border here in La Parada.

“With scrap metal, what I make in one month in Venezuela, I make in one day here,” he explains, adding that the money goes to help his family eat. He lives with his grandfather who looks after Breiner's two younger siblings so his salary matters.

He’s been doing this since the start of the year.

“The situation is really difficult,” he says. He can’t vote but it doesn’t stop him having an opinion on his country’s politics.

“No one wants Maduro, he treats people really badly,” he says. “We need a change.”

As the sun starts to set, more and more Venezuelans head back over the bridge, their jobs done for the day. Food purchased, medical appointments met. One passer-by loaded with nappies shouts “what a humiliation” - people having to leave their country to buy basic goods so they can survive.

But even as the afternoon fades, there are still plenty of people still trying to enter Colombia. They’re queuing up along a bright yellow metal fence, like corralled cattle, waiting for their turn to show their documents and be allowed in.

From the bridge where the maleteros are, you can see a blue-painted cage. Inside is a figure of the Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Virgen del Carmen). She’s the patron saint of drivers and of the Army in the Andes. In a part of the world where hope is fading, faith remains strong. Fitting too that her home is an insecure frontier town, an area where soldiers operate around the clock.

A figure of the Our Lady of Mount Carmel

The virgin sits across a dirt road, in front of a metal yard where Pompilio Rincon is throwing slabs of aluminium on to a scrap heap.

He says there are lots of metal collectors that come over from Venezuela.

“Before, Venezuelans would come in their cars and trucks,” he says. Now, people are bringing metal on their backs - women and children too.”

As he chats, a young teenager in a smart checked short-sleeved t-shirt comes in with a big bag and dumps his treasure on to the massive set of scales on the floor of the warehouse. He hopes to get 1,500 pesos (50 cents) per kilo of his metal.

Scrap metal dealer Pompilio Rincon with young collector Breiner Hernandez

Breiner Hernandez, 15, comes from San Cristobal in Venezuela. He goes to school in the morning and when he’s not studying, he’s looking for metal. Every few days he jumps on the bus with his bag to sell on the other side of the border here in La Parada.

“With scrap metal, what I make in one month in Venezuela, I make in one day here,” he explains, adding that the money goes to help his family eat. He lives with his grandfather who looks after his two younger siblings so Breiner’s salary matters.

He’s been doing this since the start of the year.

“The situation is really difficult,” he says. He can’t vote but it doesn’t stop him having an opinion on his country’s politics.

“No one wants Maduro, he treats people really badly,” he says. “We need a change.”

The Bolivarian National Guard - Venezuela's army - usher them through to the Colombian side. On one fence, there’s a billboard.

The sign reads "Territorio de Paz" or Territory of Peace.

“Territory of peace” it reads. But one soldier mutters. He sounds fed up. He may work for the government but he suffers the same as his compatriots. His salary doesn’t stretch and he can’t eat a decent meal.

“I wonder how long I can last here,” he tells me as he too contemplates his escape.