Putin’s secret weapon: The threat to the UK lurking on our sea beds

Shortly after midday local time on Christmas Day 2024, workers at the Finnish electricity company Fingrid noticed the main undersea electricity cable linking Finland with Estonia was damaged, significantly reducing Estonia’s power supply.

That evening, Fingrid’s network operations manager Arto Pahkin was quoted by Finland’s national broadcaster as saying: “We have several lines of investigation, from sabotage to a technical fault, and nothing has been ruled out yet. At least two vessels have been moving near the cable at the time of the disturbance.”

Hours later, a Finnish coast guard crew boarded the Russian ship Eagle S and steered it into Finnish waters. It was suspected of deliberately damaging the main power cable, Estlink 2.

The EU says the Cook Islands-registered ship is in fact part of "Russia's shadow fleet". It is suspected that the ageing tanker is used to carry embargoed Russian oil products.

Finnish police believe the Eagle S may have dragged its anchor along the seabed. An anchor was reportedly retrieved from along the route of the Eagle S, in depths of up to 80m (262ft), while photos taken since the incident showed the vessel missing its port side anchor. The Finnish police said they had nine suspects in a criminal investigation into the cable damage.

The damage to the 105-mile long (170km) Estlink 2 cable marks the latest in a series of incidents in which underwater cables in the Baltic region have been either damaged or severed completely since Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine three years ago.

Following the Estlink 2 incident, Nato pledged to enhance its military presence in the Baltic Sea, while Estonia sent a patrol ship to protect its Estlink 1 undersea power cable. The the failure of the undersea cable was the "latest in a series of suspected attacks on critical infrastructure”.

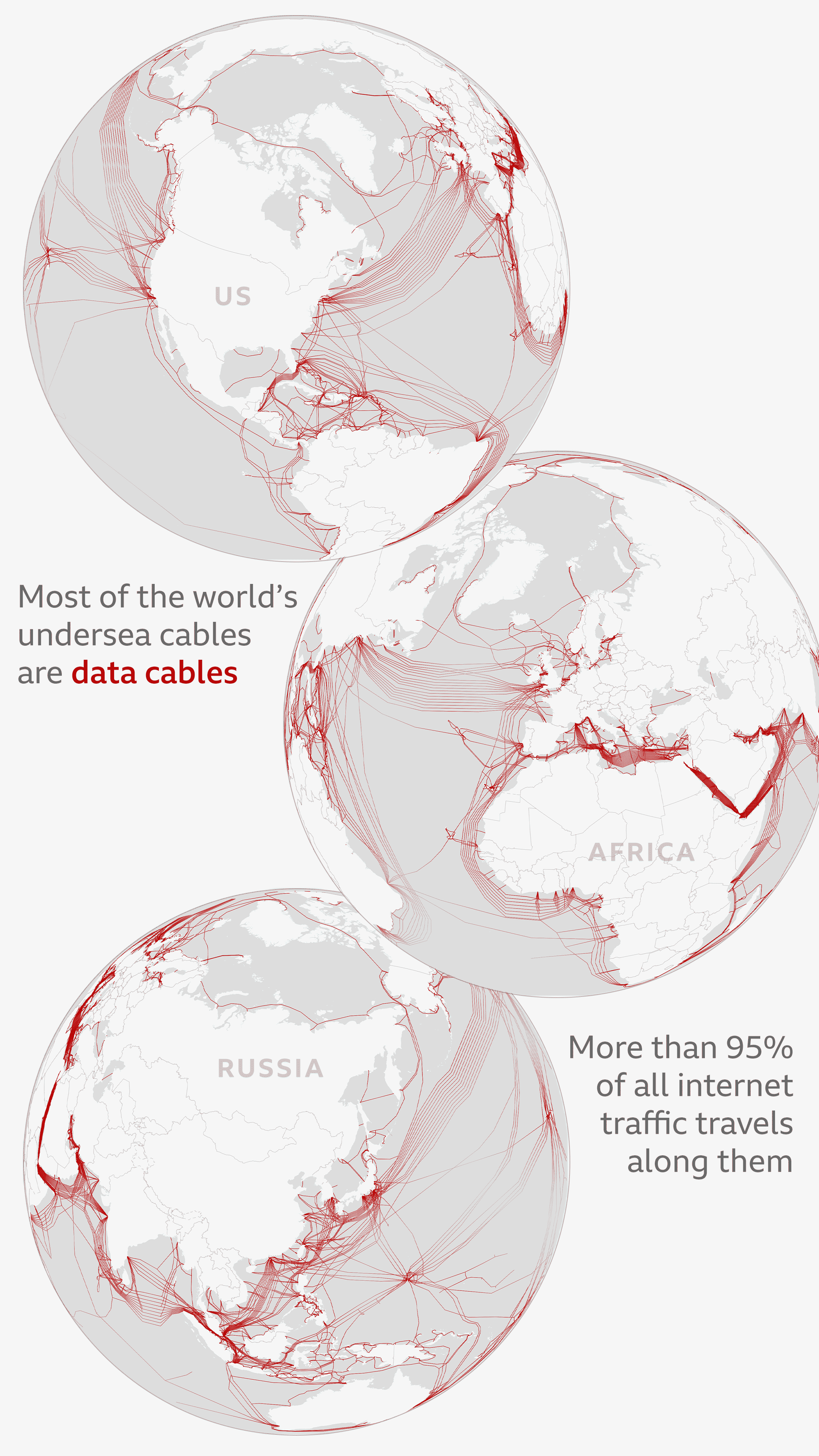

Around 600 undersea cables carry electricity and information across vast oceans and seas. Coming ashore often at discreet, secret locations, all 870,000 miles (1.4m km) of them connect us. The majority are data cables, responsible for almost all of our internet traffic.

Analysts say there is always the possibility of accidental damage or human error, but the frequency of these incidents begs the question: how exposed are these undersea cables to sabotage?

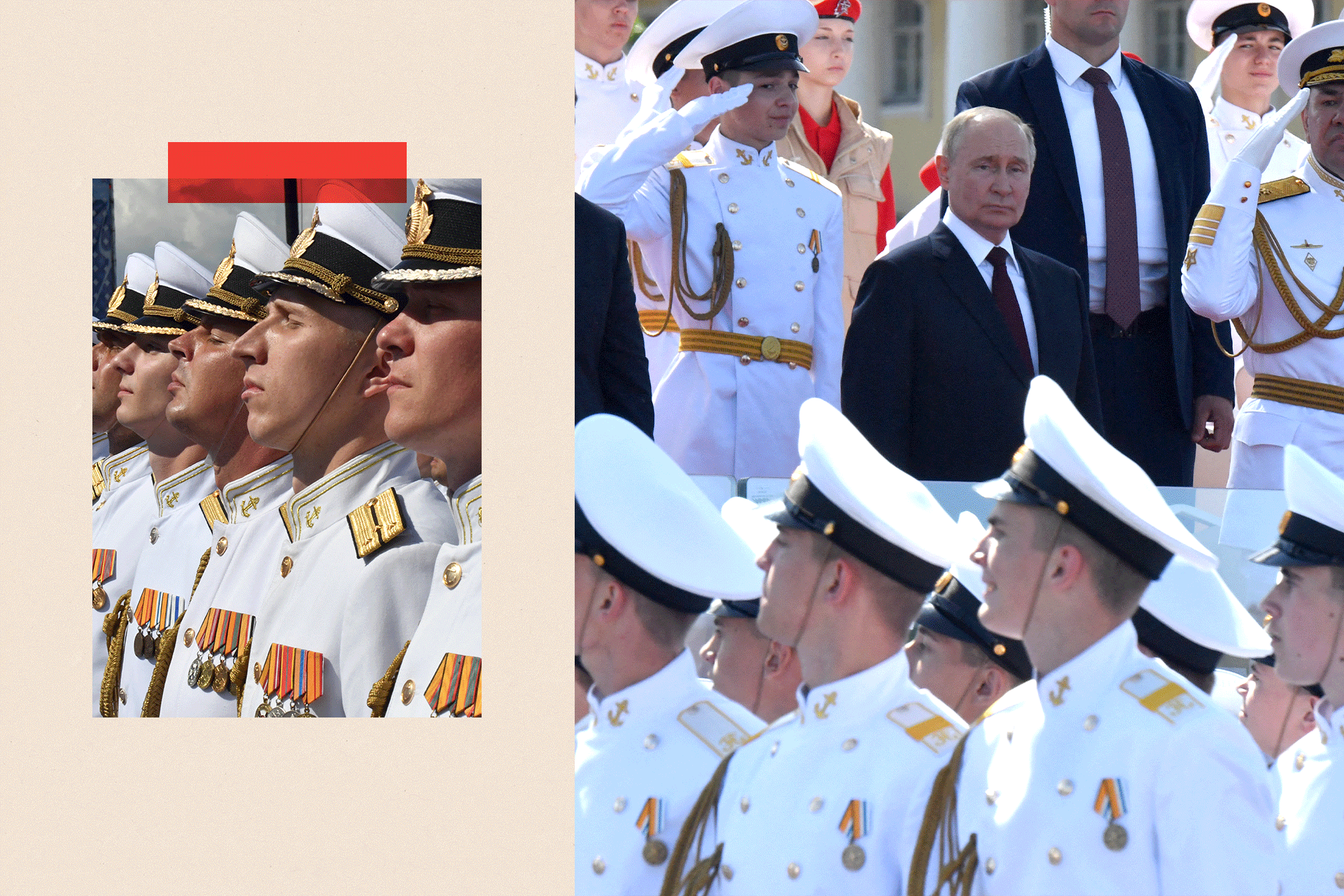

Why the West is worried

It hardly needs saying, but relations right now between Russia and most of Western Europe are close to rock bottom.

They have been strained for years, after events including the Kremlin-backed insurgency in eastern Ukraine and Russia’s occupation and annexation of Crimea in 2014.

In 2022, the West was united in outrage when 200,000 Russian troops invaded Ukraine, triggering three years of war and an estimated million people killed or wounded between both sides.

Nato believes Russia is also waging another war, an undeclared one, something called "hybrid warfare" and that the target is Western Europe itself, with the aim of punishing or deterring Western nations from continuing their military support for Ukraine.

Hybrid warfare, also called “grey zone” or “sub-threshold” warfare, is when a hostile state carries out an anonymous, deniable attack, usually in highly suspicious circumstances. It will be enough to harm their opponent, especially their infrastructure assets, but stop short of being an attributable act of war.

“Deep-diving submarines can sever cables at depths which make repairs extremely difficult,” says Dr Sidharth Kaushal, senior research fellow in sea power at the Whitehall-based Royal United Services Institute (Rusi). “They can also tap sensitive undersea cables.”

“In a conflict with Nato”, says Dr Kaushal, “damage to infrastructure at sea along with the targeting of infrastructure ashore would be a key part of Russia’s overall war effort, aimed at gradually eroding popular support in the West”.

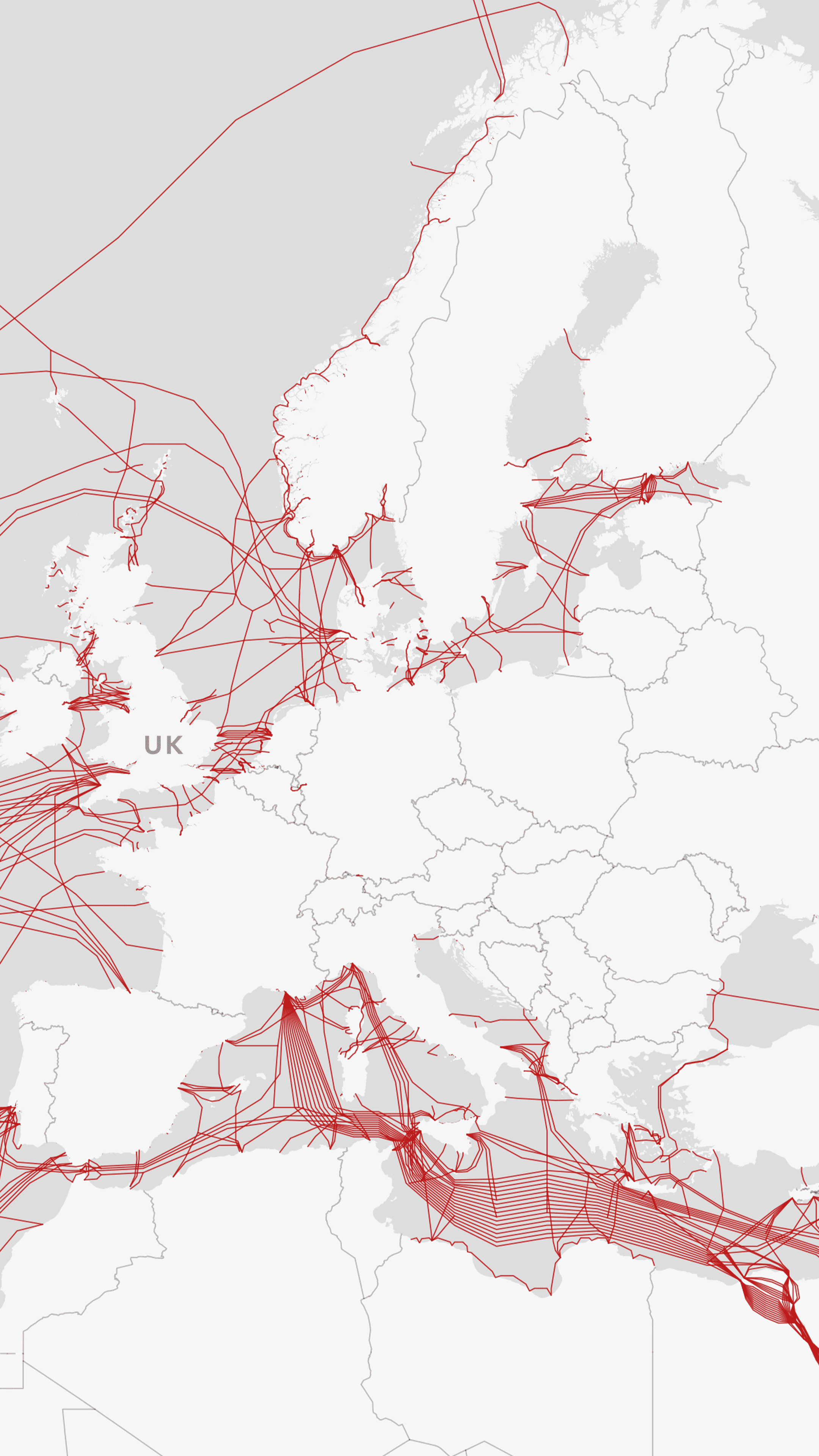

Map showing the submarine cables in Europe, image

Carrying data and electricity between countries in microseconds, Europe’s undersea cables are vital arteries

Map showing the submarine cables in Europe, with the Northern Europe and Balkans' cables highlighted, image

In recent months the Baltic Sea has become a flashpoint for suspected subsea infrastructure sabotage

Map showing the submarine cables in Europe, with the recently damaged cables highlighted, image

In November, Germany said it suspected sabotage after two fibre-optic cables running under the Baltic from Germany to Finland and Sweden to Lithuania were severed

Map showing the submarine cables in Europe, with the recently damaged cables highlighted, image

A month later, Finnish coastguards seized a tanker carrying Russian gasoline that allegedly cut an undersea power connector between Finland and Estonia

Map showing the submarine cables in Europe, with the recently damaged cables highlighted, image

Map showing the submarine cables in Europe, image

Carrying data and electricity between countries in microseconds, Europe’s undersea cables are vital arteries

Map showing the submarine cables in Europe, with the Northern Europe and Balkans' cables highlighted, image

In recent months the Baltic Sea has become a flashpoint for suspected subsea infrastructure sabotage

Map showing the submarine cables in Europe, with the recently damaged cables highlighted, image

In November, Germany said it suspected sabotage after two fibre-optic cables running under the Baltic from Germany to Finland and Sweden to Lithuania were severed

Map showing the submarine cables in Europe, with the recently damaged cables highlighted, image

A month later, Finnish coastguards seized a tanker carrying Russian gasoline that allegedly cut an undersea power connector between Finland and Estonia

Map showing the submarine cables in Europe, with the recently damaged cables highlighted, image

"Plausible deniability”

Other examples of suspected hybrid warfare attacks are the series of parcel fires targeting courier companies in the UK, Germany and Poland last year. Polish prosecutors said the incidents were dry runs aimed at sabotaging flights to the US and Canada.

Russia denies being behind acts of sabotage, but it is suspected to have been behind other attacks on warehouses and railway networks in EU member states, including in Sweden and in the Czech Republic.

These events are leading some Western governments to conclude there is a possibility Russia’s military intelligence agency may have embarked on a systematic campaign of anonymous, covert attacks on those countries helping Ukraine.

The threat has been taken seriously enough that Nato and the EU set up the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats in 2017, based in Helsinki.

Dr Camino Kavanagh, visiting senior fellow with the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, says states may be drawn to this type of warfare because “there's so much possibility of plausible deniability”.

A lot of the focus now for countries such as the UK is on “denying that deniability, from an operational perspective”. For subsea infrastructure, this requires a strong understanding of what is happening in its own waters, in order to be able to identify suspicious activity.

“That grey zone activity is something that is very, very difficult to respond to, but I think given the past few incidents, states are getting better,” says Dr Kavanagh.

What are Russia’s undersea capabilities?

The Russian military has what Rusi’s Dr Kaushal calls “quite a tiered structure”.

In more shallow waters, he says, it tends to fall to Spetsnaz (Special Forces), the GRU (Military Intelligence) and the Russian Navy. But the task of deep-sea intelligence gathering and sabotage operations is undertaken primarily by the Main Directorate for Deep Sea Research (GUGI) which answers directly to the defence ministry and President Putin himself.

The GUGI, says Dr Kaushal, uses surface ships for surveillance and intelligence gathering, such as mapping the location of offshore wind farms or the points at which cables come ashore. But for deep sea operations he says they use “mother ships” in the form of former nuclear ballistic missile and cruise missile submarines like the Belgorod.

“The Russians”, he adds, “have a diverse suite of capabilities including titanium-hulled submarines, that can operate at depths of thousands of metres and which are equipped with manipulative arms”. These three-man crews are usually highly experienced former naval officers who undergo training every bit as rigorous as those of cosmonauts.

At depths like those it is extremely challenging, even for the US Navy, to know exactly what is being placed on the seabed or what these deep-sea submersibles are up to.

Ultimately, potential sabotage to cables should be seen “as not just an isolated phenomenon” but as part of “Russia's much more holistic programme of targeting communications infrastructure and critical infrastructure overall”, according to Keir Giles, Russia expert at Chatham House and author of Who Will Defend Europe?

Russia’s focus on subsea cables and telecoms is “part of their programme of ensuring information superiority - which can also mean information interdiction". This is because if they want to cut off communities in a particular part of the world from information, other than what they are receiving from Russia, “that is seen as a very important objective because of how important it was in the seizure of Crimea”.

Loitering over infrastructure

Certainly the authorities in Finland are not alone in their suspicions regarding Russia and subsea cable infrastructure.

In November 2024 Russian surveillance ship, the Yantar, was spotted “loitering over UK critical undersea infrastructure”, according to the Defence Secretary, John Healey.

In January 2025 it apparently happened again, with the Royal Navy monitoring the Yantar, which the Ministry of Defence said was being used “for gathering intelligence and mapping the UK’s underwater infrastructure”. Healey described this incident as “another example of growing Russian aggression”.

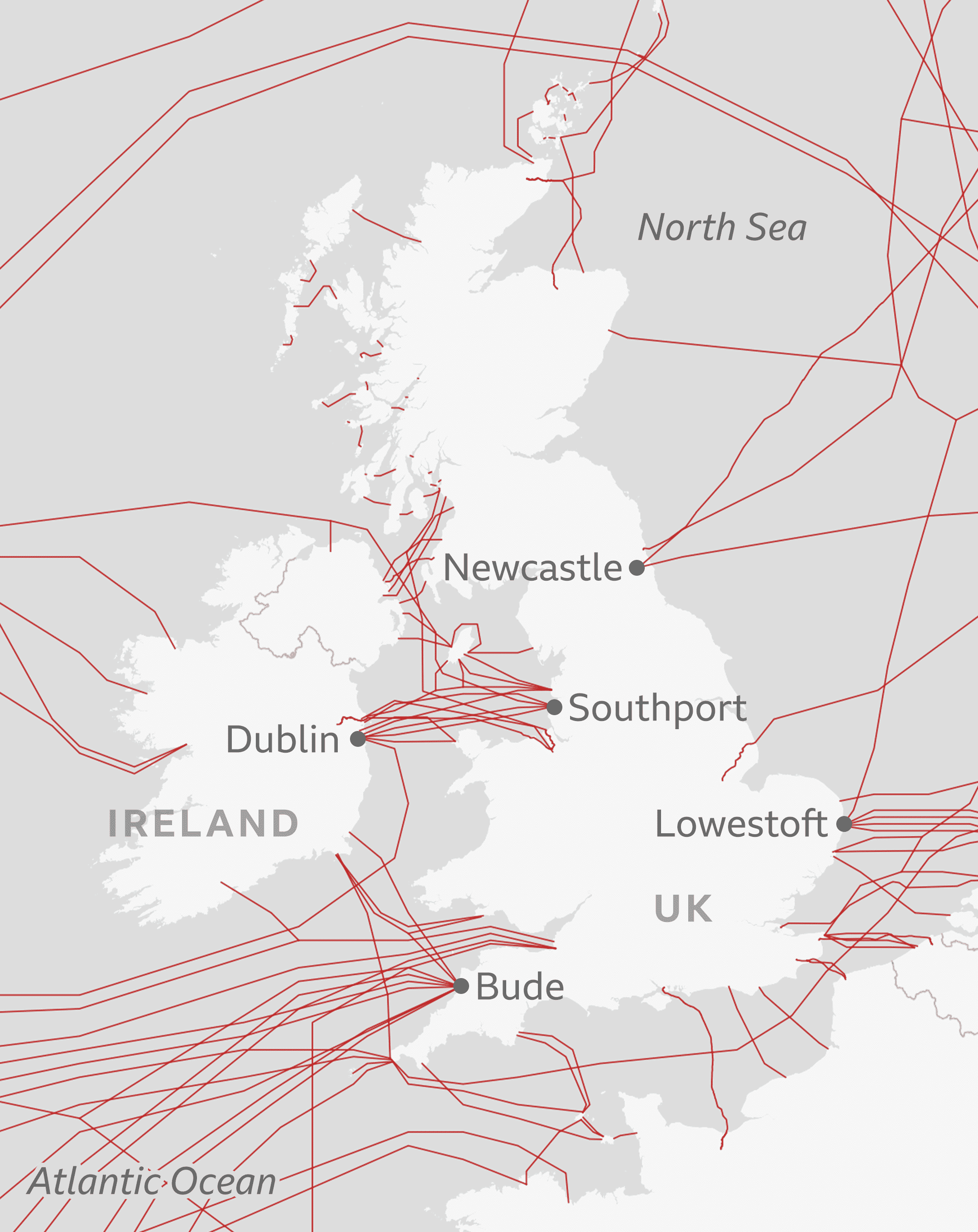

The UK has around 60 undersea cables that come ashore at various points along its coastline, with particular concentrations around East Anglia and the South-West of England.

If there were an assault of any scale on the UK’s subsea infrastructure, it would probably be accompanied by other challenges to the country's systems, Mr Giles says.

The Russian Embassy in London described the UK’s claims regarding the Yantar as "completely groundless”.

It alleged there was “a surge in anti-Russian hysteria”, which it said was being used by the UK and its allies “to deliberately escalate tensions in the Baltic and North Sea regions”.

Naïve trust

This year Britain’s Joint Committee on the National Security Strategy, which scrutinises the structures for government decision-making on national security, launched an inquiry into how vulnerable the UK is to undersea cable attacks.

“The Russians” says the author and expert on Russia, Edward Lucas, “have probably already planted their underwater drones on the seabed, waiting for orders which may or may not come, to carry out an attack on cables and pipelines. Their surveillance ship, the Yantar, has been doing God-knows-what on the seabed for years”.

The whole global network of undersea cables and pipelines, adds Lucas, was built on a naïve basis of trust.

"We never thought it would become a target of a hostile state but now we are reaping the harvest of decades of complacency. Our only hope is deterrence: showing the Russians that the cost to them of harming our subsea infrastructure would be too painful for them."

Dr Kavanagh says the UK has some resilience built into its infrastructure, because “repairs can actually happen very, very quickly”. Also, the design of subsea cables has, at least recently, been based on the idea “that they're going to break at some stage, so you need to prepare”.

Mr Giles describes the response of Western countries to recognising the challenge as “very belated”. But he says cutting individual cables would not have the amount of impact that it would have done when Russia first started looking at doing this.

This is because having multiple cables that connect the same countries using varied routes and ensuring that the repair ecosystem is resilient, are now part of the design, according to Dr Kavanagh.

She says: “It's actually quite a relief to see that a lot of countries are now focused on understanding their own vulnerabilities in terms of resilience, working more and more closely with industry."

A wake-up call

These incidents, despite Russian denials of any involvement, have served as a wake-up call to European governments that these critical lifelines are under-protected, even if it would be physically impossible to protect them all, at every depth.

Mr Giles says: “The threat has always been there. It's just that in the current environment, the threat actors feel more emboldened to actually test and probe and see what will work.”

The hybrid warfare also serves as a learning function for Russia: “They see what the impact is, they also see what the response of the target country is, the capacity for investigating, prosecuting, et cetera.”

Longer term, the deep sea capability that Russia possesses gives the option, in the almost unthinkable event of war, to do very serious damage to Europe’s economies and the daily lives of its citizens.

“And that's not just about subsea cables, that is about all of the other ways in which Russia can reach out at an enormous distance to affect people in the homeland,” adds Mr Giles.

“It is the sabotage attacks through proxies. It is cyber attacks. It is mass ransomware. It is putting the incendiary devices on airliners. And it is eventually the potential for missile strikes to come in from thousands of kilometres away with no war and no warning, because that is how Russia conducts business.”

How the West handles the threat of sabotage of undersea cables is just one of the many fronts on which it is attempting to deal with Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

The wars of 2024 brought together rivals - but created new enemies

The wars of 2024 brought together rivals - but created new enemies

The search for Ukraine's missing - 'no one could have foreseen this nightmare'

The search for Ukraine's missing - 'no one could have foreseen this nightmare'

The endgame in Ukraine: How the war could come to a close in 2025

The endgame in Ukraine: How the war could come to a close in 2025