Artificial 'embryos' created in the lab

- Published

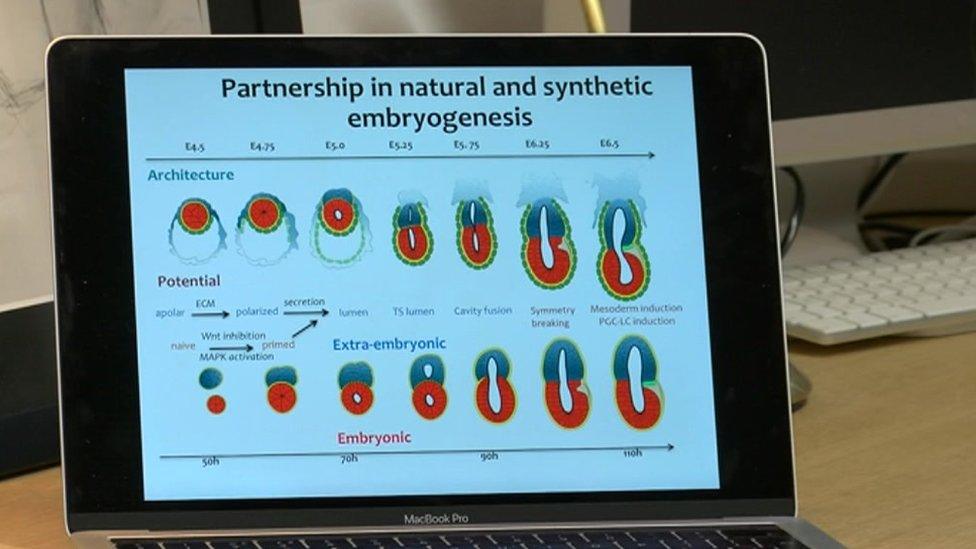

Stem cells coordinate to produce the embryo

Scientists have created "artificial embryos" using stem cells from mice, in what they believe is a world first.

The University of Cambridge team used two types of stem cells and a 3D scaffold to create a structure closely resembling a natural mouse embryo.

Previous attempts have had limited success because early embryo development requires the different cells to coordinate with each other.

The researchers hope their work will help improve fertility treatments.

It could also provide useful insights into the way early embryos develop.

However, experimentation on human embryos is strictly regulated, and banned after 14 days.

Human-pig 'chimera embryos' detailed

Should embryo research rules be changed?

Embryo study shows 'life's first steps'

Once a mammalian egg has been fertilised, it divides to generate embryonic stem cells - the body's "master cells".

These embryonic stem cells cluster together inside the embryo towards one end, forming the rudimentary embryonic structure known as a blastocyst.

The Cambridge team, whose work is published in the journal Science, created their artificial embryo using embryonic stem cells and a second type of stem cell - extra-embryonic trophoblast stem cells - which form the placenta.

Lead researcher Prof Magdalena Zenricka Goetz said: "We knew that interactions between the different types of stem cell are important for development, but the striking thing that our new work illustrates is that this is a real partnership - these cells truly guide each other."

However, the researchers say their artificial embryo is unlikely to develop into a healthy foetus as it would probably need the third form of stem cell, which develops into the yolk sac that provides nutrition.

Prof Goetz's team has a strong track record of research in embryology

The same team recently developed a technique that allows blastocysts to develop in the lab up to the legal limit of 14 days in the UK.

They have already grown these artificial mice embryos to the equivalent stage, and they are now working on using the same technique to develop artificial human embryos.

If they are successful, it could open the door to experimenting on embryos beyond the current 14-day limit.

Prof Jonathan Montgomery, an expert in health care law, at University College London, said: "It wouldn't, obviously, be within the current regulatory framework, although we would need to think carefully about how we should oversee it.

"It is early days, but if they do manage to not only create the partnership that's needed to get started but also the nutrition that's needed to sustain it, you could see that we are contemplating the opportunity of developing human embryos for quite a substantial period in vivo."

Prof Robin Lovell-Badge, of The Francis Crick Institute, said some structures seen in early embryos had failed to develop.

This, and other problems, would need to be solved before the technology could be developed further.

He also said it was unlikely that human equivalents could be developed because the necessary cells from human embryos were not available.