The revolution in broadcast technology over the last decade, combined with the way people now use mobile phones, has hastened the decline, but not yet death, of one of the ���˿���’s most humble but useful facilities: the remote studio.

From tiny ISDN (or Post Office pre-1984) junction boxes to purpose-built radio studios, whether situated in a council office or off-site venue, or housed in a smart ���˿��� regional centre, these remote inject points or studios have provided a welcome sight for decades, either for reporters trying to file stories in quality when radio cars were unavailable or out of signal, or down-the-line programme interviews to LBH or elsewhere. The recent closure of so many of them marks the end of an era in ���˿��� local broadcasting. The NCA studio network in the main local radio buildings are still active, but having used many of the more remote ones in my ���˿��� career, I wondered – ‘what stories they could they tell’.

A request for information and memories before the passage of time robs us of these stories filled my inbox with memories, part funny, part sad, but always entertaining. I uncovered gems that perhaps could only come from the ���˿��� – weird inject venues, strange studios and even stranger stories. I’ve split these into two distinct parts – firstly, the humble ���˿��� inject points and remote studios, then for another article those larger studio and district office set-ups. This is not a comprehensive history, but hopefully this will give you a flavour of their place within the ���˿���, and a smile from those who used them.

Patchwork quilt

It’s a stretch to say that other than the basic NCA network it’s ever been a single managed system. Over decades, a patchwork quilt of studios and inject points opened for many reasons, not just as for news or events. Local radio stations in England were the backbone of the network, with remote studios in outlying towns helping to augment their county coverage. Large counties like Cumbria, Kent, Sussex, Devon and Yorkshire had them based in geographically remote towns, usually situated in council buildings. Editors would always stress control of content and usage rested with that station and the ���˿���. I am sure if you add up all these strange rooms, nooks, crannies and cupboards, it would be an extraordinary amount of real estate.

Not all are easily accessed. A familiar scenario was in Hampshire, where there was an NCA studio in a basement on Winchester High Street. You had to get the keys from a British Gas shop over the road, hoping it was not the town’s shopping half-day. In East Sussex, there was a remote studio at Haywards Heath, which the ���˿���’s late cricket correspondent, Christopher Martin-Jenkins, often filed from. It had a single button to use, which often proved one button too many for a technophobe like CMJ. He was therefore excited when the new Horsham studio opened, because it was much more convenient for him, being five minutes from his house.

Some inject points were situated in very odd places indeed. Radio Lincolnshire’s Spalding studio was in the local swimming pool, in a room underneath the foot bath, and which leaked. Every few months the station’s engineer had to drive over and clear the mould off. A temporary studio was in a disused mortuary in Sandown on the Isle of Wight, set up for the week-long coverage of an attempt to rescue a man from a crumbling well. The local engineer admitted later: ‘Network paid. I got quite adept at squeezing money out of them for lines. The studio somehow became permanent. The man died.’

Window ledge broadcasts

Peter Gore, ex-���˿��� staffer, wrote to say: ‘My father Sydney was the engineer at the start of ���˿��� Southampton at Southwestern House. He always told me he’d installed a broadcast point on the window ledge in a hotel room of the Globe Hotel in Cowes on the Isle of Wight. It was in a room overlooking the sea, and was simply a terminal into which the output of a broadcast could be plugged. It was used mainly for OBs during Cowes Week in the early days. I don’t know if it’s still there, and sadly my father died some years ago.’

Facilities were basic. Radio Merseyside’s remote studio in Chester used a mixer from one of the main studios made obsolete by a refurbishment. Had the engineers ‘forgot’ to send it to the redundant plant department? A weakness was that the equipment was too complex for any member of the public to self-operate, so unless the Chester producer was in situ and willing to help there was no way a local might contribute to the output. A different story though if it was a network programme. The eventual move to digital ISDN enabled direct connections to other places, but prior to that some jiggery-pluggery would have been required. Cheshire’s PR man, who knew how to work the kit, earned a lot of beer money by ‘meeting and greeting’ contributors to the Today programme, Good Morning Wales, etc. Even Radio Merseyside might have taken a cut!

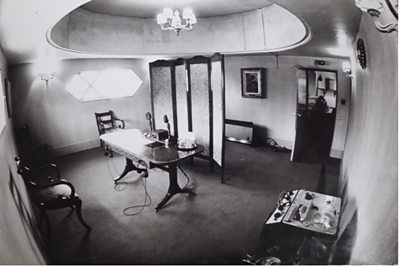

There was even a remote studio in the old TV Centre reception in Wood Lane. Guests could be directed to it by the receptionist. Inside there was a phone, mic and headphones, with instructions on how to contact the radio station’s programme. Very handy for getting hold of visiting politicians and celebs on air, it was specifically positioned there to avoid having to have to use a costly ‘meeter and greeter’.

Meeter and greeters

‘Meeter and greeters’ were and still remain a vital cog in the operation. Coming from all walks of life, mostly non-broadcasting, they are on permanent call to ensure a sometimes-nervous guest is met, installed and able to operate the studio for their contribution, then lock up afterwards. It’s a part operational, part ambassadorial role, and they’re proud to do it. One is the ���˿��� Carmarthen keyholder, Gwynn Bowyer (pictured below), who died in the summer of 2024. A fervent Welsh patriot, he was the ‘meeter and greeter’ from its opening in 1993. My old ���˿��� colleague Lawrence Hourahane paid this tribute: ‘Completely reliable, one of those people who make programmes happen. I’d never met him, but week after week he’d agree to open up for our sports reporters and camera staff. Programmes wouldn’t have got on air in their entirety without him, and others like him the length and breadth of the UK.’

Essentials

���˿��� local radio manager Mike Marsh set up many offices and studios during his career. ‘In Northampton, I persuaded the local authorities in Corby, Kettering and Wellingborough to provide rooms as studios in their HQs. One news producer was based in Corby, and we also had a journalist in Wellingborough.’ Marsh had no doubt about their value. ‘All were essential to ���˿��� local radio’s public service role through sustained, relevant coverage of each station’s editorial area. Those stations at the time had some of the highest ���˿��� Local Radio audience figures.’

Graham Moss was Radio Cumbria’s Assistant Editor for many years, spending time in both Whitehaven and Barrow: ‘The management gave me the chance to present the opt-out Radio Furness breakfast programme in Barrow. There was no online listening in those days, so you could do pretty well what you wanted without the bosses hearing. Although there was a rumour the Programme Organiser at the other end of the county had a special aerial to keep a check, I was never called in for questioning!’.

Empire building

Some stations used district offices as crafty pieces of empire building. Eric Wise worked at Radio Merseyside. ‘Our flagship district studio was in Chester, over 20 miles from our base. Cheshire never had its own station, and was ‘served’ not awfully well by Merseyside, Manchester and Stoke, with a tract of no-man’s land around Northwich. A deal was struck with Cheshire Council where they provided space in County Hall, and for many years a reporter/producer worked prodigiously from there, frequently turning out two or three packages a day.’

Wise later recalled a brush with Hollywood. ‘I did go to the Chester studio soon after leaving the staff in 2007 to interview actor Mickey Rooney for the World Service. He got lost looking for the ‘bathroom’, and was somewhat underwhelmed by the whole set up! The council was dissolved in 2009, and last time I passed by it looked as if County Hall had been turned into student accommodation.’

Presenter Alex Trelinski remembered well the Radio Humberside set-up, where its HQ in Hull and the Grimsby district office were separated by the mighty Humber estuary. ‘It had a couple of journalists, Mike Cartwright and Alan Cuthbertson, two hours were broadcast live from 2pm daily with Barry Stockdale, and there was a secretary/receptionist too. The station itself had six NCA contribution studios – it was like presenting a mini version of Nationwide!’

Another ���˿��� local radio station had begun life as the experimental ‘���˿��� Radio Blackburn’. When the concept of county stations emerged, ‘���˿��� Radio Lancashire’ was decidedly off-centre. There’s a tale, no doubt apocryphal, that two chaps from ���˿��� property arrived in Blackburn, identified a suitable building, signed on the dotted line, then realised they should have been ten miles away in the county town (now city) of Preston. In an attempt to redress the balance, a shopfront was opened between Preston’s bus station and the market. This was a studio and public counter, where punters could place record requests, pick up a car sticker or photo of their favourite presenter or buy a station mug. ���˿��� Radio Sussex had a similar shop set-up on the ground floor of their Brighton district office.