My story begins in Loughborough, where I was born in 1940. My childhood days were accompanied by the haunting sound of a WW2 air raid siren. Our terraced house was next to the fire station, which had the warning apparatus installed on the roof.

After the war, Bryony, my eldest sister, attended a local dancing school to learn ballet and tap. Each year they put on a pantomime with Dame Billy Breen, who years later gained TV fame as Larry Grayson. Being Bryony’s brother, I was enrolled to operate the footlights. On the first night, Larry saucily flashed his knickers at the audience and I intuitively shone a red spotlight on his legs. This got a big laugh, so we kept it in for the week.

With no academic qualifications and school behind me, I needed a job. I decided on an apprenticeship at the town’s biggest employer, Brush Electrical Engineering. But in truth I dearly wishing for something more creative.

During my apprenticeship at Brush, I indulged my passion for films and took an unpaid job as projectionist at town’s Victory Cinema. When I was on duty, the regular staff would leave me to run the whole show, operating the 35mm projectors, the house lights, curtains and the reel change-overs. I was in my element and loved being in charge. Even then I was drawn to the production of films and had favourite directors like David Lean, Billy Wilder and Carol Reed.

Both parents knew I wanted to pursue a more artistic vocation, but in the 1950s the regions had no TV companies and I lived 100 miles from London. So, how could I break into films? To explore this elusive choice, my father and I went to see his friend, John Cox. A former Loughborough Grammar School pupil, now living in Buckinghamshire, John was Head of Sound at Shepperton Studios, working mainly on David Lean epics.

He was extremely helpful and we considered various options, but in the end his advice was to try the ���˿��� and the burgeoning TV business. John reasoned that the ACTT Union was still powerful in features. They also had the reputation for making it difficult for studios to recruit new staff. To get a job, you had to have a Union card – and to get one of those, you had to have a job. This stranglehold on the industry was not recognised by ���˿��� Television.

I’ve never believed in fairies, but one was about to make a timely appearance. My father had noticed a Volkswagen van around Loughborough with ‘David Clarke Film Unit’ painted on it. Meeting this David Clarke could be the answer, so we phoned the number displayed on the van and arranged to see him one evening.

He was a kindly, urbane fellow who had competed in motor racing the 1950s, so his plan was to produce motor sport films. I was impressed, but one question lingered: how could I be part of this ambitious venture? Well, it so happens David was looking for someone to train in all aspects of film making, and he thought I fitted the bill. I couldn’t be happier, as David’s offer gave me entry into the film business.

David Clarke – my mentor

Joining David Clarke proved significant, especially as he was generous in sharing his knowledge, so I would learn a great deal from him. We hit it off immediately, so I handed my notice in at Brush, breaking my five-year apprenticeship, and started with David early in 1958.

Silverstone became my first location as David was contracted by Castrol to cover the Touring Car race at the non-championship Formula One Daily Express Trophy in May 1958. This was my first taste of an F1 meeting. Before, I hadn’t given it any thought, but the moment we arrived in the Silverstone paddock I was hooked by the noise, the frantic action, even the smell of engine oil (a fish-based lubricant known as Castrol R).

My first F1 race as a cameraman was the International Trophy at Silverstone in 1959. Juan Manuel Fangio, now retired, was there to start the race with the Union Jack. I captured this moment from my vantage point on the inside of the front row of the grid. Once I began working for David, I became acquainted with 16mm which was a large step into the professional world. Indeed, the ���˿��� had recently started using 16mm, having discarded the heavy 35mm equipment.

In 1960, David bought a French 35mm Cameflex camera to shoot cinema commercials. That same year we were commissioned by MGM to film the action scenes at Le Mans for The Green Helmet starring Bill Travers. David and I were approached at a F1 race at Silverstone when testing the camara by two MGM executives. The Born Free actor played a racing driver in the film. As we were not members of the ACTT Union, our involvement was a clandestine one. My main memory of the Cameflex was it sounded like a machine gun when filming.

Meeting Enzo Ferrari

It was David who gave me my first chance at directing. In 1964, ‘250GT’ was a profile of Ferrari road cars that were also successful on the race tracks. The commentary was by Raymond Baxter and Michael Parkes; the latter worked as an engineer and works driver at the factory in Italy. Michael played a significant role in getting permission for us to film the production lines and to have a private audience with Enzo Ferrari.

Back in the UK we took the red Lusso out to get some shots of David at the wheel. We were parked in a lay-by between takes when a police patrol car pulled alongside. All they wanted was to have a good look at the Ferrari. David suggested that one of them might like to have a drive. Quick as a flash, one jumped into the driver’s seat and was off. David recalled his experience as a passenger watching those great black boots hitting all three pedals at once and flashing past a stately driven Rover. The old chap had noticed the cops in the lay-by, and seemed to be mouthing, ‘That’ll teach you!’ Little did he realise the Ferrari was now driven over the speed limit by a policeman!

David’s film unit regrettably closed in 1959, but during my time there I felt editing gave me the most satisfaction. Therefore, my ambition was to get a job where editing would be key.

London-bound in 1962

My first editing job in London was for Stanley Schofield Productions in Bond Street on Flying Scotsman, the famous locomotive then owned by Alan Pegler. The ���˿���’s Johnny Morris of Animal Magic added a most entertaining commentary, thus lifting the final production.

By now I was living in Middlesex, which made it easier to meet people who worked at the ���˿���. In 1965 a friend put me in touch with Peter Cantor, a film editor on Panorama, who knew a manager who was looking for holiday relief editors. I rang Peter’s contact, the softly spoken John Priestley, who invited me for an interview one morning over a cup of tea in the Ealing canteen. The result: I was offered a six-month contract, followed by another extension which became permanent.

Initially I worked for ���˿��� Enterprises at Woodstock Grove. This department shipped ���˿��� programmes abroad, ranging from Andy Pandy to Z Cars. After a few months learning the ropes, I was moved to Lime Grove Studios, home of Panorama and 24 Hours, where I found the editing exhilarating.

I was fortunate to work with many fine reporters and journalists, including Fyffe Robertson, David Lomax, James Mossman and Michael Charlton. Within a very short time I felt the ���˿��� was right for me. After all, I now had a secure staff job as a film editor – so had I achieved my goal? Only time would tell!

I have two memories of Fyffe Robertson. Firstly, when he was surprisingly caught speeding in London and his case came up at Battersea Crown Court, I went with to keep him company. He was fined (no points on your licence then), and with the ordeal over we drove to my nearby flat for tea and toast. Secondly, when he and his wife Betty accompanied me to see Max Wall in a variety show in Bournemouth. This occurred when I began looking for the chance to make a documentary about Max and was hoping Fyffe would be the presenter.

Socialising at the ���˿��� could mean joining a football team. Although a rubbish player, I turned out for General Features when I worked on That’s Life with Esther Rantzen and a series called The Americans with her husband, Desmond Wilcox.

The art of film editing was most rewarding. In Current Affairs, especially 24 Hours, you had the added pressure of transmission deadlines, usually on the same night, so an adrenaline rush added spice to the steep learning curve. The ���˿��� therefore became my seat of learning, making it a really creative and dynamic place to work. I gained my ‘spurs’ on Current Affairs and this continued into my editing of documentaries.

The rewards were directors like Geoff Dunlop, Jeremy Bennett and Richard Taylor would ask me to edit their films. As editors we watched miles of rushes that needed assembling in a way that made an impact on viewers. This aspect excited me, so I began to think I could try my hand at directing. My sense of rhythm enabled me to ‘edit in my head’ and to call ‘cut’ when I was sure we had enough film in the can.

Some of the most fulfilling series included The Americans with Desmond Willcox. This focused on archetypal figures in the USA such as Hollywood actress Jodie Foster. Still a teenager, she came to London with her mother to see the finished film. After the viewing I escorted Jodie back to Desmond’s office, where he’d put on some very tasty refreshments. Jodie was asked to direct a short sequence in the States, which I edited in London, and she loved the result. Jodie has since directed features, but I’m able to claim I edited her first experience of life behind the lens.

My first stop in directing was the flourishing corporate field, which gave me a great start to my new career. Peter Cole, former producer on Panorama, gave me my first directing job, a video for Sperry Gyroscope. During that period, many ���˿��� colleagues were to be found in the freelance market. Peter Cole was not alone in this exodus. Bernard Falk, whom I worked with when he was a reporter on 24 Hours, also joined the corporate world.

For Falkman Films, I directed a production for Renault Trucks. I travelled the UK with Bernard in his Audi; that included to Bonny Scotland. One day we happened to finish shooting at lunch time, so Bernard decided to call and see his drinking mates at ���˿��� Glasgow. I could see what would happen. Yes, that evening I drove us back to our hotel in Edinburgh along unfamiliar roads in the gathering gloom. On the way, Bernard kept slapping my knee and saying, ‘You’re doing a great job Paul, a great job.’

Freelance television directing post-���˿���

My move back into television as a documentary director came in 1980. Firstly, I went to Southern TV to direct a film about the Australian GP driver Alan Jones, who won the 1980 World Championship for Williams. Then to Granada to direct a network series called Jobwatch, followed by a documentary for Melvyn Braggs’ South Bank Show on the drama group inside Wormwood Scrubs Prison. Instead of Melvyn’s usual studio introduction, we filmed that in the High Security wing, which added great atmosphere to his piece and our film.

For my second South Bank Show, I was in touch with my Music Hall clown, Max Wall, who had become a celebrated actor thanks to his affinity with the unconventional playwright Samuel Beckett. Max re-invented himself as the embodiment of Beckett’s troubled characters on stage and TV. This earned Max a different audience and much applause, in fact a swansong he well deserved. One of the sequences we filmed was Max reading Malone Dies at the 1984 Edinburgh International Festival.

Max Wall had been a great friend for over 20 years. When he died in 1990, admirers got together and formed the Max Wall Society. I was delighted to be one of the Chairmen who hosted the annual dinner at the National Liberal Club for members, known as Bricks. Other famous Bricks were Alison Steadman, Simon Callow, Barry Cryer and the ‘Harry Potter’ actor David Bradley. Guests who attended these feasts included Prunella Scales, Ian Lavender and Wayne Sleep. Ronnie Corbett and Ken Dodd became Presidents.

Death of my mentor

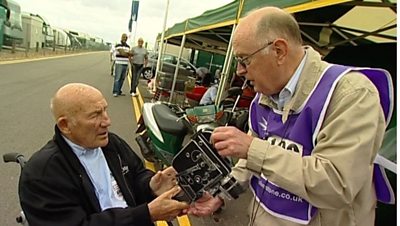

When my mentor David Clark died in 2002, he was the subject of a ���˿���2 documentary on his extraordinary life and devotion to funding worthy causes. I was one of the friends interviewed on camera, praising his exceptionally generous spirit. Raymond Baxter was also filmed. Speaking to a packed church at his funeral in Loughborough, I read out touching messages from Stirling Moss and Raymond Baxter, who had both been impressed by the modesty of this shy man.

In conclusion

Looking back on my 15 years at the ���˿���, I cherished my career there which set me up to become a freelance documentary director. To me this was a natural career move; taking a desk job would have wasted those exhilarating times at the ���˿���!

If I’ve not always succeeded in recalling A Film Buff’s Life, perhaps I should end by quoting a perceptive line from Samuel Beckett: ‘No Matter, Try Again, Fail Again, Fail Better.’