It’s thirty years since the first ever episode of The Vicar of Dibley. As a television comedy about a woman vicar, it was designed to be a groundbreaking series at a seminal moment in the history of the Church of England. It was also funny – and sometimes rude. But, as David Hendy writes, the fictional Reverend Geraldine Granger, played by Dawn French, was just one in a long line of comedy priests that have appeared – sometimes controversially - on ���˿��� television over the years.

On Thursday 10 November 1994, British television viewers were transported for the first time to what the Radio Times called “a perfect village somewhere in England” – a village where, as we can see here in the series’ opening scene, “none of the villagers are quite ready” for the arrival of their brand new vicar:

Religion has never been an easy subject for the ���˿���.

Its Founding Father, John Reith, was the son of a church minister and famously touchy about it. In the 1920s, one of his lieutenants declared, without hesitation, that “We are living in a Christian land.” Yet one of Reith’s other lieutenants said that broadcasting was – even then - “an entertainment medium”. And if comedy is on the ���˿���’s programme menu, so too is poking fun – especially poking fun at figures we see as too serious for their own good. Comedy also tends to work best when it identifies something that audiences recognise as true.

How, then, has our national broadcaster navigated the choppy waters of representing the figure of ‘the priest’ in its comedy programmes over the decades? How has it attempted to create characters that might be funny and realistic?

The Green Book Era

In 1948, the Corporation gave every impression of wanting to duck such awkward questions altogether. Its ‘Variety’ department published a set of guidelines for writers and producers which became known as the ‘Green Book’. The document’s overriding message was clear:

Programmes must at all cost be kept free of crudities, coarseness and innuendo.” As for the portrayal of religious characters, it banned “any sort of parody” of Biblical figures, and jokes about “religious ceremonies of any description.

One regular contributor to the Variety department who laboured under these sweeping restrictions – but who always tried to find a way around them – was the humourist Frank Muir. In this interview for the ���˿��� Oral History Collection, he describes his testy relationship with one particular producer at the time:

“Daffy Parsons”

In the 1960s, producers were increasingly determined to circumnavigate restrictions that were more than a decade old. And producers in television were even more determined to do this than their colleagues in radio. So by 1967, it no longer felt especially daring to launch a comedy programme all about priests and their funny ways.

The series – All Gas and Gaiters - began in January 1967, with an episode called ‘The Bishop Gets the Sack’. But there’d been a pilot episode eight months earlier, as part of Comedy Playhouse, the ���˿���’s testing ground for new comedy. ‘The Bishop Rides Again’ established All Gas and Gaiter’s all-important setting: the fictional St. Ogg’s Cathedral. It also featured its three leading characters: the archdeacon – a man who likes his sherry – played by Robertson Hare; the bishop – a bit of an old bluffer – played by William Mervyn; and the good-hearted but rather naïve and bumbling chaplain, the Reverend Mervyn Noote, played by Derek Nimmo.

When the series proper was launched the following January, one TV critic reflected on what he called the “silly ass” characters he’d just watched. The typical Catholic priest, he pointed out, often did well out of his fictional portrayal:

Producers see him as a man of the world with a taste for whisky, a classless, lovable man, with a tongue on him perhaps but with a heart of gold.

The Anglican was less fortunate. He – and it was very much still a ‘he’ in 1967 - might be benign, even scholarly. Switched-on he was not. So in Dad’s Army - another series that began in the late-1960s - we saw, for instance, the wimpish, gullible and sulky ‘Reverend Timothy Farthing’ alongside his absurdly sycophantic verger.

In All Gas and Gaiters, Nimmo’s Mervyn Noote offered viewers yet another unworldly and ineffectual creature, complete with fluted voice and Cambridge accent.

It was funny, or so our TV critic thought, simply because “pretentious people are funny” and the Church of England “with its curious clobber and fancy titles invites ridicule.” As for the reaction of the Church itself, the Provost of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Edinburgh suggested that the “daffy parsons” of All Gas and Gaiters proved one thing above all else: that mockery remained “the commonest weapon against Jesus Christ and his followers”.

The wider critical response to All Gas and Gaiters was, to say the least, mixed. What offended many newspaper reviewers wasn’t some frightening lapse in moral standards by portraying clerics in this gently satirical fashion. In 1967 there were plenty of other things to unsettle the especially sensitive TV viewer: the long-haired hippies of the ‘summer of love’, the ‘turn on, tune in and drop out’ rhetoric of the counter-culture, campus sit-ins, protest marches – the kind of things sometimes lumped together by an older generation and placed in the category of what Anthony Burgess – after watching just one episode of Top of the Pops - called Britain’s “ignoble descent into mindlessness.”

From a comedy point of view, the deeper problem with All Gas and Gaiters was that it represented a style already past its sell-by-date. “I cannot say I found it very funny, or indeed, funny at all”, the Guardian critic wrote, before adding “most of the little old ladies I know like it”. It gave off “a comforting air that everything is as it always was and will never change … It is cosy, full of open fires and lovely old rooms with fresh flowers from the garden and tea and crumpets about to be served.”

It seemed, though, as if cosy tea-and-crumpets was exactly the kind of stuff lots of viewers wanted. All Gas and Gaiters ran for a grand total of five series, only ending in 1972.

Unsurprisingly, the ���˿��� thought it wise to come up with a spin-off of some kind. So in September 1968 it launched Oh, Brother!, set in the fictional Mountacres Monastery and featuring Nimmo in the starring role of Brother Dominic – who, though now a northerner, was still clumsy and inept:

Oh, Brother! clearly mined much the same seam of gentle farce as All Gas and Gaiters. But it ran for only three series. A monastery was perhaps simply too closed a setting for the variety of fresh material required to sustain a programme over the long-term.

It wasn’t until 1986 – more than a decade later, and in the middle of Margaret Thatcher’s premiership - that Nimmo once again appeared on the ���˿��� in full religious garb. His vehicle this time around: a comedy called Hell’s Bells, set in what the Radio Times described as ‘the cosy cloisters of Norchester Cathedral’.

By now, Nimmo has been elevated to the role of Dean. And in the first episode, ‘On Your Bike, Pilgrim!’, his character, ‘Dean Selwyn’, faces the arrival of a new Bishop, played by Robert Stephens – a man with outspoken socialist ideals. Note the backdrop in this opening scene. In one of its more radical departures, the tea-and-crumpets have been replaced by tea-and-toast…

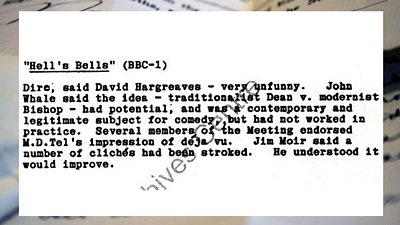

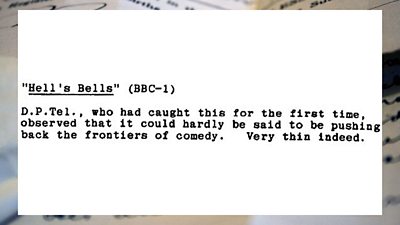

Hell’s Bells lasted just a single series -a telling moment in the history of TV priests. Behind the scenes at the ���˿���, senior programme-makers would gather for their weekly ‘Review Board’ to discuss the last seven days of TV output. When they did so in the summer of 1986 and came round to discussing Hell’s Bells, the judgments were damning – as these two extracts from the minutes reveal:

Tearing up the rule books

‘Dire’. ‘Very unfunny’. ‘Very thin indeed.’ It’s safe to assume that Hell’s Bells’ shortened life was a belated recognition by Britain’s broadcasters that the earlier stereotype of the Anglican priest had run its course.

But perhaps wider changes behind-the-scenes were having an effect, too. The department charged with making the ���˿���’s religious programmes – programmes such as Songs of Praise and Everyman on TV, or Thought for the Day and the Daily Service on the radio – had no direct responsibility for the Corporation’s comedy output, of course. But attitudes revealed in one corner of the ���˿��� sometimes offer clues to attitudes in other parts of the machine.

Colin Morris, a former Methodist missionary, had joined the ���˿���’s Religious Broadcasting department in 1977 and stayed for the next nine years – most of that time as its head. In an interview recorded for the Corporation’s own oral history collection, Morris, a lifelong advocate for inclusivity, explained how one of the programmes he managed, Everyman, was introduced precisely in order to show the relevance of religion to everyday social issues:

There was a generational changeover in comedy, too. And in the mid-1990s it coincided with one of the most tumultuous transformations then taking place within the Church of England itself: a move to allow women priests.

For programme-makers, this was too good an opportunity to miss. And The Vicar of Dibley was conceived as a determined – if light-hearted – piece of advocacy for this new departure. Its writer, Richard Curtis, admitted to having a “bee in his bonnet” about the ordination of women after attending a friend’s wedding – as he explained in this 1995 edition of Everyman. In the programme, we also see Joy Carroll, one of Britain’s first ordained women and the real-life inspiration for Dawn French’s lead character, ‘the Reverend Geraldine Granger’:

The “confrontational approach” Joy Carroll talked about in that clip wasn’t really the ���˿���’s preferred style, either. But Richard Curtis wasn’t interested in creating a shrinking violet.

As he gleefully noted, Joy Carroll herself was “as naughty and irreverent and ‘like us’ as you could hope.” The character of Reverend Geraldine Granger - feisty but with a weakness for wine, chocolate and romance - was also all too human, all too fallible. And part of The Vicar of Dibley’s appeal was the guaranteed supply of slightly risqué gags and saucy dialogue it managed to smuggle onto primetime television under the sheep’s clothing of a cosy setting.

You can see a typical slice of it here in the opening scene of the 2004 Christmas Special, when the Reverend Granger turns up for a village committee meeting that’s already begun without her:

Crucially, as Wendy Sherer shows in her own ground-breaking research, Geraldine Granger finally provides us with a vicar who is no longer the butt of every joke.

Dawn French’s character was sharp-witted. In a village where it was almost everyone else, no matter how ‘lovable’, who was either foolish or odd, she was often the lone voice of reason. Ultimately, she was also the voice of compassion. Her parishioners might drive her to distraction. But in the last resort, she would never condemn them. Despite her frustrations and occasional doubts, here was a vicar who might get the better of those who oppose her. But she was always dedicated to her calling.

Here, in that 1995 Everyman documentary, we see Dawn French in conversation with Joy Carroll. The actor clearly felt the generally warm reception the series received offered her scope to push an already rambunctious and worldly character even further in future series:

And push it, the series did – though not just over Dawn French’s role.

Paul Nicholson, the real-life vicar of the church in which the series was filmed - in the village of Turville, Oxfordshire - claimed in an interview that the character of Geraldine Granger sowed ‘Christian seeds’ by ‘doing things’ – demonstrating ‘faith in action’. It might be true, as its producer, Jon Plowman, explained, that Dibley was essentially “a show about a quirky community and about the difference between rural and urban Britain”. But its co-writer Richard Curtis was keen to create a vicar who didn’t always avoid controversial social and ethical issues. Reverend Nicholson himself, usually on hand to advise the programme-makers, was a life-long champion of the underprivileged – a campaigner for radical policies to tackle poverty and homelessness. And over the twelve years in which the series was screened, it’s no surprise that themes of social justice regularly informed the plotlines.

Was the rather delightful village setting of The Vicar of Dibley, the very best location for exploring issues like hunger or poverty, though?

The ‘real-life’ Reverend Granger, Joy Carroll, was a London vicar, and told the Everyman documentary team in 1995 that, unlike her fictional counterpart, she couldn’t ever see herself working in the countryside. “I have a keen interest in people’s social welfare … as well as issues around justice and equality” she explained. “The city seems to be the place where these issues are at the forefront.”

And it was the city – inner London, to be precise – where the next fictional television priest would pop up on the ���˿���, when, in 2010 it introduced to ‘Reverend Adam Smallbone’, the lead character of Rev.

Searching for authenticity

Over nineteen episodes spread across three critically acclaimed series, Rev attempted the tricky balancing act of being funny while portraying as authentically as possible the working life of an urban vicar. The title role was played by Tom Hollander, who also wrote the series with James Wood.

Given the thoroughly contemporary inner-city setting, Hollander and Wood wanted to show that in a church such as the Reverend Smallbone’s St Saviour in the Marshes ‘working life’ meant a daily battle with the realities of poverty, loneliness, addiction, inter-faith relations, a crumbling church fabric, and – in the very first scene of the very first episode – a dwindling congregation:

Like Dawn French’s Geraldine Granger, Adam Smallbone is an all-too-worldly, all-too-human vicar - someone who smokes and drinks and swears. Like her, he’s dedicated to his calling. The social problems he has to deal with are on another scale, however: this is a time and place where, in terms of welfare support, the vicar was sometimes not just the last but the only resort. His power to change deep-rooted social problems are limited, of course, and by the third series Adam becomes increasingly vulnerable to severe doubts about his faith.

This darker tone was what distinguished Rev. from all its predecessors. It wasn’t recorded before a live audience. Nor was there any attempt to deploy a ‘laughter track’. Hollander even tried to remove some of the jokes. Above all, as the series producer, Hannah Pescod, explained, the programme-makers “didn’t really make much up”: its storylines were based on many months of observing and understanding and being in constant dialogue with real-life vicars running churches located right in the thick of the most challenging of social environments.

For all the messiness in Adam’s life – perhaps precisely because of the messiness in Adam’s life - we remained on his side. Here was a tragic figure we sympathized with, not least for his desire to change what, in the end, could not be changed. Here was an Anglican priest but also an Everyman. Here, quite simply, was A Good Man.

Perhaps only one question remained for television’s comedy scriptwriters. Were Britain’s viewers ready for a priest who might in some sort of way be A Bad Man? Were they ready, in fact, for a vicar with sex appeal?

Hot Priest

Fleabag, written by and starring Phoebe Waller-Bridge, was never about priests or religion or faith – at least, not in any direct way. But its second series, screened in 2019, introduced us to ‘Hot Priest’ – a part played with aplomb by Andrew Scott. His character was, as it happened a Catholic priest, not an Anglican. Which – recall those newspaper comments from 1967 – gave the series licence to make him “a man of the world with a taste for whisky, a classless, lovable man, with a tongue on him”. It also required him to be celibate – which added to the sexual frisson after Fleabag’s main character first meets him during a family gathering at a restaurant:

‘Hot Priest’ quickly became the vicar as social media meme – a character chewed over and psycho-analysed in countless blog posts and newspaper articles. One columnist likened him to Colin Firth’s Mr Darcy stepping from a lake in a wet white shirt. Another called him “an exploitative muppet”.

Though Andrew Scott’s character seemed so brilliantly contemporary and fresh, he couldn’t really be classified as the ‘ultimate version’ of British television’s comic priest. Between the two series of Fleabag, the ���˿��� launched This Country, a series which features yet another vicar – the Reverend Francis Seaton - who, in many ways, seemed like a cross between Dibley’s Geraldine Granger and Rev’s Adam Smallbone: someone in a rural backwater tending, like a one-man social service – and with little thanks - to people who clearly got little help from their own families. Not so much a return to the original as a novel re-mix. There will, no doubt, be other versions we can’t yet visualise.

What connects all these characters - past, present, and future; ancient stereotypes alongside convincing takes on the real thing – is one thing above all others, namely the innate comic potential of an enduringly strange role. Beyond the exotic clothes and the sometimes arcane language, there’s the job. The hope of changing lives in a predominantly secular and material world in which you are vested with little real power. The need to forget for the sake of your own sanity that you are massively over-educated for the task of putting on a jumble sale.

They say the vital ingredient of all comedy is a healthy dose of tragedy. If that’s so, it would seem that the British television priest has long been the perfect tragi-comic hero.

Written by David Hendy Emeritus Professor, University of Sussex.