Women first trained for jobs in the ���˿���'s Engineering Department in 1941, to fill roles vacated by male engineers serving in the war. What do newly released oral histories reveal about women's experiences in this previously male-dominated area of broadcasting?

By the end of the Second World War, 800 women had been trained at the ���˿��� Engineering Training School. They were initially employed in radio, on maintenance and programme work as well as on radio transmission stations. They acted as Programme Engineers controlling the audio output and providing sound effects, and in transmitters, switching signals and performing routine maintenance.

Women became adept at recording broadcast material on various types of recording media, including steel-tape recording, disc recording, and recording on film. They also worked as blueprint tracers, drawing diagrams and circuit boards in the Civil Engineering Department, and in the Equipment Department they were engaged in winding coils to create electric currents with a strong electromagnetic field.

Women with education and experience in mathematics, science, or engineering-related industries were sought to fill the new position of Women Operator, later renamed Technical Assistant (TA).

Dorothy Preston was one of the first women to be employed as a TA. As she recalls in this oral history interview, technical engineering jobs were attractive alternatives to clerical and factory work, particularly for those with a technical bent:

The new recruits had varied backgrounds. Mary Ticehurst had worked for the Express Lift Company in Northampton, and Gladys Davies came from the printing industry.

The ���˿��� Engineering Department also found women with a background in dramatics or creative fields desirable, particularly if they had musical training. Being able to read a musical score enabled women to monitor sound levels, and drama skills were useful for programmes that required creative sound effects.

A good level of educational achievement was also key. For example, Mary Ticehurst's grammar school education, together with her experience working in an electrical goods showroom, and a background in amateur dramatics, made her an attractive candidate. She was first employed by the ���˿��� on the broadcast transmitter at Daventry during the war.

There was some resistance from male engineers to women working in the Engineering Division, according to Dorothy Preston, who recalled that, "not only did they resent us women, but they also were terribly afraid of losing their own jobs".

There was certainly resentment after the war, according to oral history accounts by women working as engineers in television, when men returning to their civilian lives wanted to be reinstated in their old posts.

After the War, the ���˿��� did not require any of the women to relinquish their broadcasting jobs, but they were relocated off transmitters to work in studios.

In her ���˿��� oral history interview, Mary Ticehurst recalled the work she did at the Daventry transmitter, which involved cleaning and changing valves, monitoring levels and patching programming on a switchboard, activity affectionately referred to as "dial twiddling".

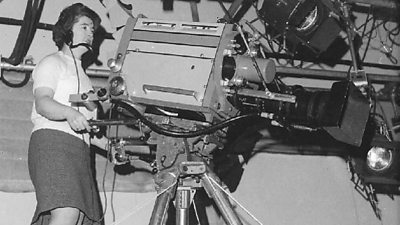

In this excerpt she talks about the work she did after her move from Daventry to the television studios at Alexandra Palace, where she became the first female television vision mixer:

In the immediate post-war years, many women remained in engineering as the reintegration of male employees from the military services took many years.

There were limited opportunities for training and promotion in that period however, and by the early 1950s the number of women engineers was reduced to a quarter of what it was during the war.

Marriage and maternity were other factors in the decreasing number of female technical staff. The ���˿��� did provide maternity leave, but shift work, along with social expectations, made continuing in service difficult for many women technicians.

Many women seized the opportunity to gain experience in as many areas of television production as possible and sought out new skills and possibilities of promotion.

At Alexandra Palace, Molly Brownless and Bimbi Harris both worked on cameras and sound and Elizabeth Macgregor gained some experience in sound mixing, although she subsequently worked solely as a gramophone operator.

In this rare oral history interview, former engineers, including Ticehurst and Harris, recall their experiences of working at Alexandra Palace in 1946:

By 1955, restructuring in the ���˿��� meant that women already employed as TAs in London were no longer allocated a wide range of technical jobs and were limited to either vision mixing or gramophone operating.

The coming of commercial television in competition with the ���˿��� in 1955 and the ���˿���’s own rapid expansion of television, led to women being recruited to the Engineering Division in the regions.

Ada Hakeney started at ���˿��� Manchester in 1954, initially in technical operations in the control room, before moving to Leeds in 1970 where, unusually, she filled all the operational posts in the television studio, including camera, leading to a profile of her in the ���˿��� staff magazine Ariel.

The Leeds lads just accepted it. And this is why they made a fuss in the Ariel about it, because normally women didn’t work in the television studio, the women worked in the gallery, doing vision mixing and things like that, they didn't work on the studio floor. So I was probably the first woman to work on the studio floor with a camera.

After moving to Cardiff in 1978, when her husband was relocated there, Hakeney worked on telecine as a fully qualified engineer, until her retirement in 1982.

Despite this, there are few other examples of women being employed in the ���˿��� Engineering Division in subsequent years.

In 1973 Barbara Franc became the first woman to be employed as a ���˿��� camera assistant, coinciding with the internal report , which highlighted the lack of opportunities for women, and the Engineering Department was particularly mentioned in this context.

Change was still slow to take place in the ensuing decades, in spite of anti-discrimination and equal opportunities legislation in the 1970s, and an Equal Opportunities officer being appointed in 1986.

Ten years later, in 1997, Liz Forgan, former Managing Director, ���˿��� Network Radio, gave a lecture for the Women’s Engineering Society in which she expressed her concern that women were "still clearly - and in some ways shockingly - unrepresented" in Engineering in the ���˿���. She argued that whilst the digital revolution may offer more opportunities for women, there were also risks that these areas of broadcasting would remain male-dominated.

Her message to women working in the ���˿���, or aspiring to, was that there should be high expectations for change, and that women must continue to battle for equality and progress in their working lives.