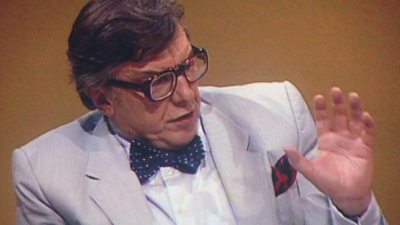

Image: Robin Day and Margaret Thatcher limber up for battle on Panorama in April 1984.

For many seasoned politicians in the years immediately after World War II the broadcasting studio offered a welcome break from the cut and thrust of Parliamentary debate. The pre-War age of deference persisted at the ���˿���, but a new generation of reporters and journalists was emerging that would challenge all that.

Politicians too began to recognize the advantages, especially in the evolving television service, of communicating directly with constituents and publicly engaging in the national conversation. For the ���˿���’s Leonard Miall, head of Television Talks, ‘the moment Churchill and Attlee left and Eden and Gaitskell took their places ……they immediately began changing the attitude of politicians to television’.

General Election coverage and the development of ‘current affairs’ broadcasting from the 1950s also heralded a step-change in relations between broadcasters like Robin Day, and the politicians they interviewed. Here Ludovic Kennedy discusses this theme (in conversation with John Cain in 1986).

Former Chief Whip, Chairman of the Conservative Party and ���˿��� Secretary, William Whitelaw, was also struck by the radical change that was under way:

Questioning was really quite simple and rather friendly, and then gradually it did get very much more extreme and in a way one had to get used to it. Some people never did get used to it, and I think it’s probably occasionally going too far now. I think there are occasions when it almost looks as if it’s a sort of competition, that the person who’s doing the interviewing is trying to show that they are cleverer than the person they’re interviewing.

Experimentation with different styles of interview technique was a dominant theme in the 1950s. New genres of political broadcasting were given added impetus through the increasing competition, from 1955, between the ���˿��� and Independent Television. However, for broadcasters such as Cliff Michelmore, it was the requirement to pin down evasive politicians that spurred their early thinking.

As techniques evolved particular personalities came to be associated with certain interview styles. Ludovic Kennedy, for example, preferred to ‘put somebody sufficiently at ease to … make him feel that he wants to say things and then I would put in a question which would challenge what he was saying’. Others chose a more direct and, sometimes, confrontational approach. Amongst these was Robin Day who was often criticised for taking too tough a line in political interviews.

For some, this was an approach that did little to illuminate, failing to recognise some of the constraints that politicians worked under. As the ���˿���’s former Political Editor, John Cole, pointed out, 'no politician can afford to say the whole truth. He can tell the truth and nothing but the truth but he’s not free to tell the whole truth'.

For Cole, a duty to 'dig beneath the surface and find out what’s going on' was not synonymous with an aggressive style.

Some politicians survived the ordeal of an interrogating interview better than others. Harold Wilson, who Robin Day described as 'the first professional television Prime Minister', thought that a hard interview got the best out of him. Moreover, Wilson argued, 'You get a bit of viewer sympathy, I think. They love to see a clash.'

John Cole believed that Margaret Thatcher was possessed of 'a kind of enamelled self-confidence about her policies' which didn’t allow for much dialogue. Day thought her a most remarkable politician to interview: 'she alone of all the Prime Ministers... has not fallen into the style of responding to the interview game. She just goes on to say what she wants to say, irrespective of the questions.'

In tandem with General Election coverage through the 1950s and 1960s, the broadcast political interview has undergone a radical transformation. No longer a measure of deference in British society, it emerged as a powerful vehicle for public accountability – albeit too aggressively so, for some. In the arms race between broadcasters and politicians it has become an established battleground where reputations and careers are both made and broken.

-

39.6 MB

-

14.1MB

-

10.3 MB

-

21.5 MB

Robin Day: The Grand Inquisitor

Robin Day arrived at the ���˿��� in 1954 after a brief period as a barrister in London and a stint at the British Information Services in Washington. These experiences would prove invaluable in his future career as a cross-examining journalist who rewrote the rules of political interviewing.

His application for a job at the ���˿��� came via a lunch with Stephen Bonarjee, a leading light in the development of current affairs, at the White Tower Restaurant in London. As Bonarjee later recalled,

Robin was a so-called penniless barrister when he was introduced to me by Honor Balfour [Time Magazine’s political correspondent in London]. … Well, there it was, he was an ex-president of the [Oxford] union and I’ve always felt that ex-presidents tend to make rather good producers and so we gave him a short term contract … Well his quality was soon apparent, but it wasn’t so much flair. I don’t think you could honestly say that Robin Day has a great deal of flair, but he had enormous diligence. Vastly thorough in everything he does, a natural interrogator: he wants to know.

Hired as a broadcaster and producer, Robin Day also remembered his induction into the peculiarities of working life at the ���˿��� in the mid-1950s.

After only a year at the ���˿��� he departed to become one of the first newscasters at the newly-minted Independent Television News (ITN). It was here, under the guardianship of Geoffrey Cox that Day developed his distinctive interview technique and reputation for persistence.

Returning to the ���˿��� after a failed attempt to win election as the Liberal candidate in Hereford in 1959, he took over the reins of Panorama after the death of Richard Dimbleby. Between 1964 and 1997 he provided expert analysis, innumerable interviews and anchoring duties on the ���˿���’s General Election results programmes. He also presented Radio 4’s The World at One and was the first Chair of ���˿��� One’s Question Time.

'Did you threaten to overrule him?'

When, in May 1997, Newsnight presenter Jeremy Paxman confronted the former ���˿��� Secretary Michael Howard over the controversial dismissal two years earlier of the head of the Prison Service, Derek Lewis, it instantly became a cause célèbre of political interviewing.

In the context of Howard’s Conservative leadership ambitions and over the course of an eight-minute interview, Paxman posed the same question 12 times without a satisfactory answer.

The refrain of ‘Did you threaten to overrule him’ subsequently came to denote a high watermark in the style of persistent, robust, but cordial interviewing technique pioneered by Robin Day and others 40 year earlier.