When people across the United Kingdom tune in to the General Election results – whether on television, radio or digitally – they are participating in a national democratic tradition.

There are key, familiar moments... The race to count and report the first declarations. Analysis by expert statistical and political commentators digesting the results from 650 individual constituency battles. Swings and swingometers dominate screens as the numbers are crunched in order to calculate the public mood. And well-known political figures may unexpectedly fall from grace and recounts be demanded.

Like all traditions, however, this one had to be invented. And in January 1950, a ���˿��� television producer called Grace Wyndham Goldie took on this task.

Here she explains how it came about...

Since its beginnings in 1922 and under the leadership of its first Director-General John Reith, the ���˿��� had attempted to avoid political controversy. For Reith, politics was 'the cringing pursuit of popularity'. Moreover, it was a potentially dangerous subject for a Corporation whose Licence Fee, from 1927, depended on the political will of Parliament.

This instinctive aversion to the coverage of politics characterised ���˿��� output from the 1920s through to the end of World War II. With the ���˿���’s embryonic television service not resuming its post-war activities until 1946, listeners simply tuned in to the radio to hear the election results read by an announcer, much as they had for the previous two decades.

In 1950, the plot hatched by Grace Wyndham Goldie and reporter Chester Wilmot for the first ever election night television programme with reporters and commentators, though limited, set the template for all General Election results programmes to come.

It was a leap of faith into the unknown. Would the transmitters, as one senior engineer put it, simply ‘explode’ if they had to run through the night? How would the ���˿���’s News Division react to another department, Television Talks, taking the election initiative? Above all, what would audiences think?

On the evening of 23 February 1950, after Polling Stations had closed, ���˿��� television began its first ever results programme. It was a tentative start, reflecting anxieties about the role broadcasting should play in British politics. But this experiment, as Grace Wyndham Goldie soon noted, ushered in a compelling new genre of broadcast output that has been a key feature of our political landscape ever since.

Who was Grace Wyndham Goldie?

Grace Wyndham Goldie has been described as dominating, quixotic, prejudiced, sharp-witted, perfectionist, practical, something of a bully – and, above all, obsessed with both television and the workings of government. She believed politics was important – and that standards mattered on the ���˿���. Being in charge of General Election broadcasting suited her down to the ground.

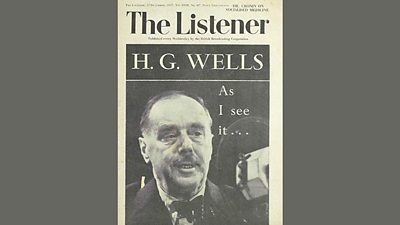

Her ���˿��� career began in 1935 when she took up the job of radio drama and entertainment critic for the ���˿���’s upmarket literary magazine, The Listener.

Her editor, Rex Lambert discouraged her from writing anything about the ���˿���’s fledgling television service. ‘It will never amount to anything in your or my lifetime’, he told her. Goldie ignored him. For several years afterwards, her columns dissected the emerging studio techniques and editorial challenges of the new medium. She wrote that television should offer viewers ‘the unmistakable feeling of direct experience’.

Towards the end of WWII in 1944 she became a producer in radio ‘talks’. This was a part of the Corporation which, according to her biographer John Grist, was ‘tinged with more than a trace of arrogance’ - though also ‘a sense of duty towards the discovery and dissemination of the truth’. She worked at Alexandra Palace and later Lime Grove – both rather drab and down-at-heel working environments, but both usefully remote from Broadcasting House, with its senior managers and fixed attitudes.

It was in these north and west London outposts of the Corporation that, as Assistant Head of Talks and then Head of Talks and Current Affairs, she recruited a remarkable team of producers, directors and reporters who would later become household names - and helped forge techniques and rituals of political television that would last well beyond her retirement in the mid-1960s. It was a formidable achievement, especially for a woman in the very male-dominated world of News and Current Affairs.